Thanks to its convenient location within the Vladimir-Suzdal principality, by the 17th century, Palekh had an established icon painting school, having soaked in several traditions at once: Novgorod, Stroganov, Moscow, Yaroslavl and Shuya. The ancient center of icon painting, the town of Shuya, lies just 30 kilometers away from Palekh. In modern Russia, both Palekh and Shuya are part of Ivanovo Region.

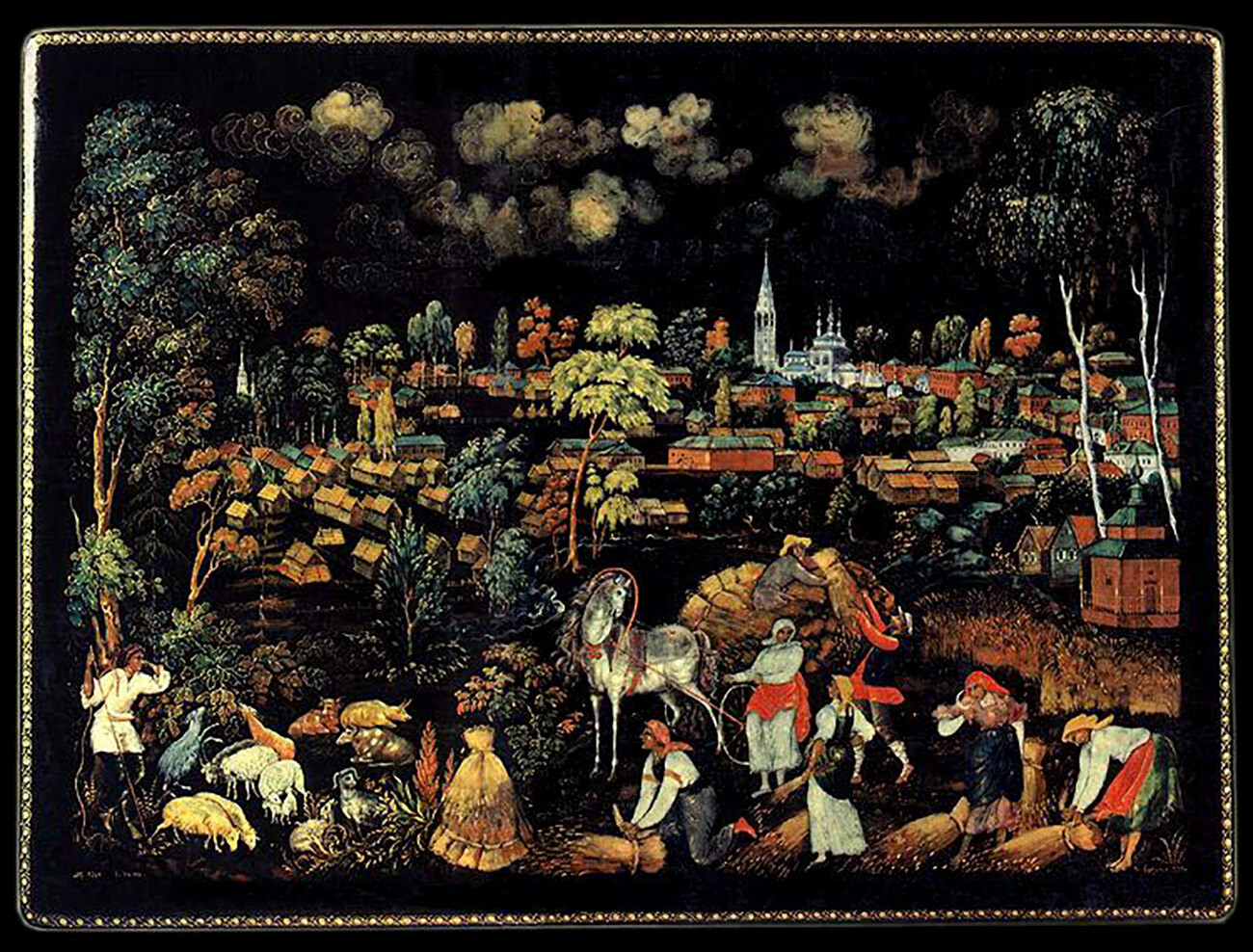

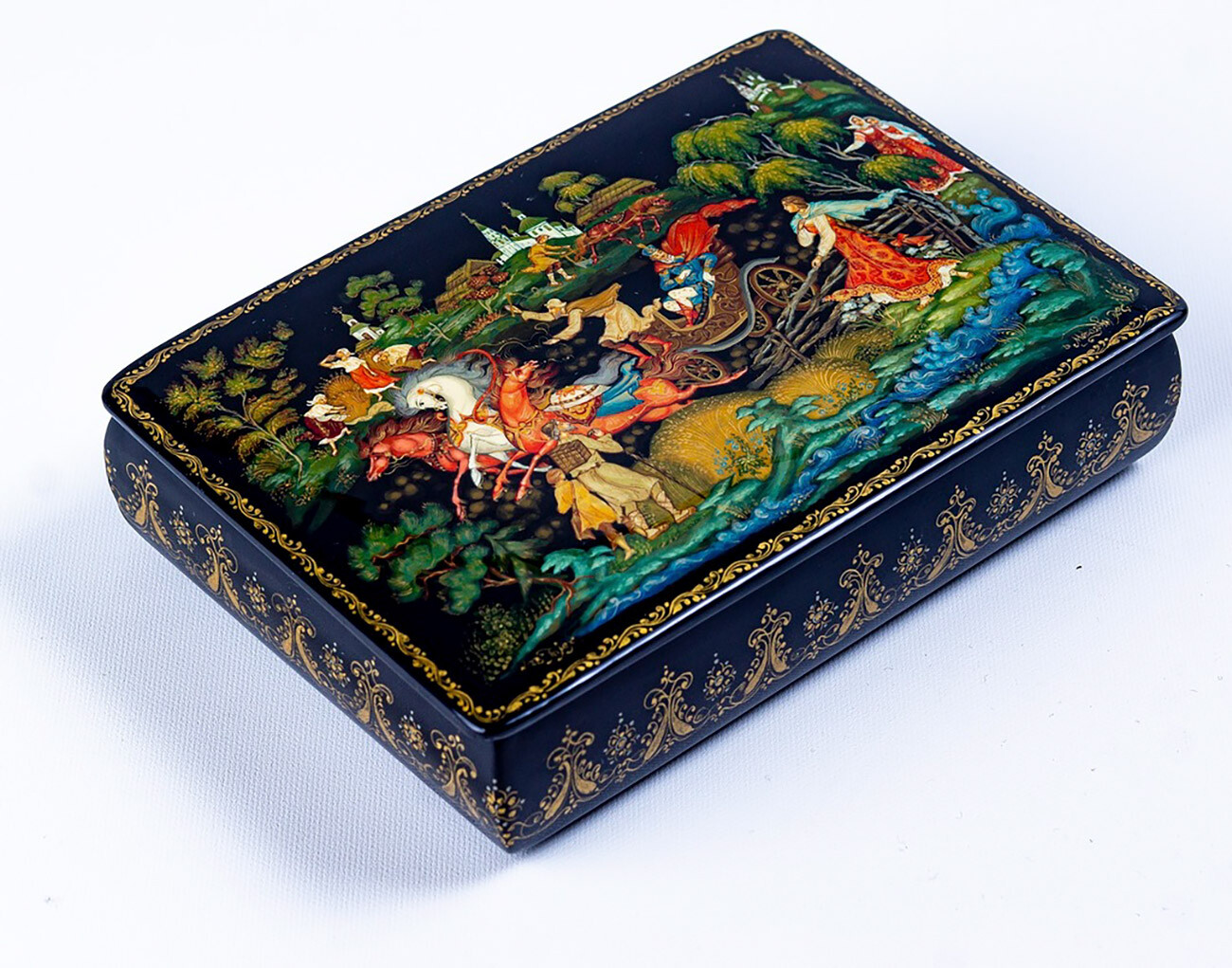

I. Bakanov. Palekh. Box, 1934.

Public domain“We believe that Shuya icon painting has a very strong influence on Palekh painting, but the foundation of the craft, of course, despite all the influence, is the Stroganov style [it was named after wealthy salt industry merchants the Stroganovs, because it showed itself best in a range of art pieces linked to their name],” artist Svetlana Shchirova, head of the Palekh Artists Association says.

“Palekh artists incorporated many styles because they traveled a lot. They went to paint and restore the Palace of Facets in Moscow, the Novodevichy Convent, the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra; they traveled to St. Petersburg, to the Urals, and accepted expensive icon commissions. They were called upon, sometimes they were even forced, ordered to come.”

Khazov. ‘Yermak’s Campaign’. Box, 1935.

Public domainThis continued for several centuries, until, in 1917, after the October Revolution, the Palekh denizens faced a choice: to let their icon painting tradition perish or to adapt to the new conditions, when everything linked to the Orthodox Christian faith was being eradicated. “The artists simply didn’t know what to do with themselves,” Svetlana Shchirova explains. “There was nothing they could do after the revolution. During summer, they plowed the fields, during winter they painted.”

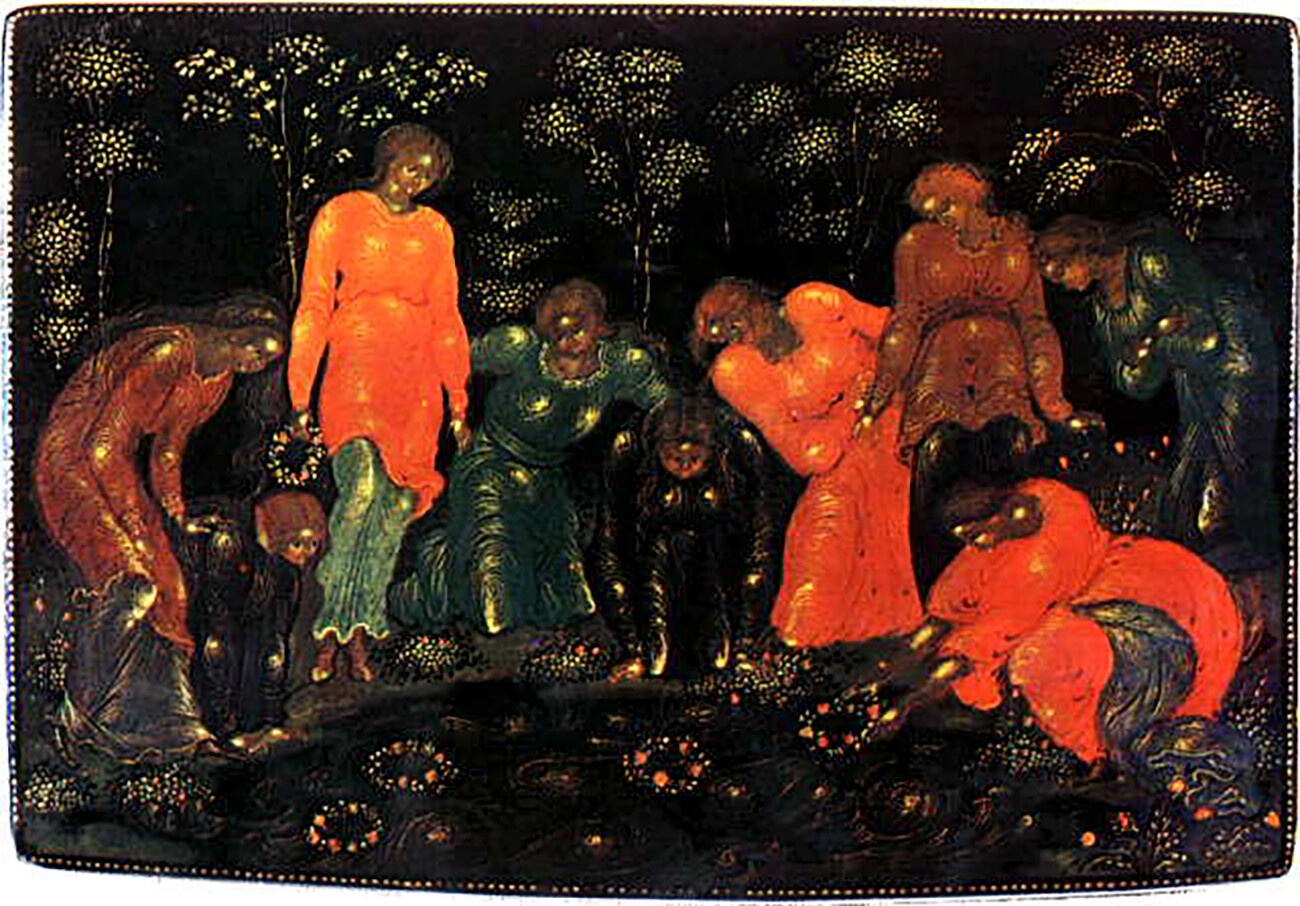

Ivan Golikov, ‘Fortune Telling on Wreaths’, 1920s

Public domainThey tried many things, including painting on wood, but they ultimately settled on Fedoskino lacquer miniature painting on papier-mache with a black background. Instead of religious motifs they had secular ones: “Fedoskino box painting played its role. The traditions of the 17th century were preserved in the craft: if there were trees painted on a box, by their shape, the thin layer of paint and their gold, they were painted as if on an icon.” As such, the most ancient icon painting tradition was preserved in the art pieces of a hundreds-of-times lesser scale and the Soviets sold these art pieces overseas.

Ivan Golikov, ‘The Third International’, 1927

Public domainPalekh icons were distinguished by their elegant thin painting style, for their detailing, abundance of gold and transparent gleaming colors. The mastery was passed down from father to son; it was known for its “small” works, meaning small icons with several narratives. That also played its role in the transformation of the Palekh icon painting into the Palekh lacquer miniature. Ivan Golikov, one of the hereditary Palekh iconographer artists, after the Revolution and having come back from World War I, found himself in a country that had no place for icons. He worked with theater props and, in 1921, he painted his first papier-mache box.

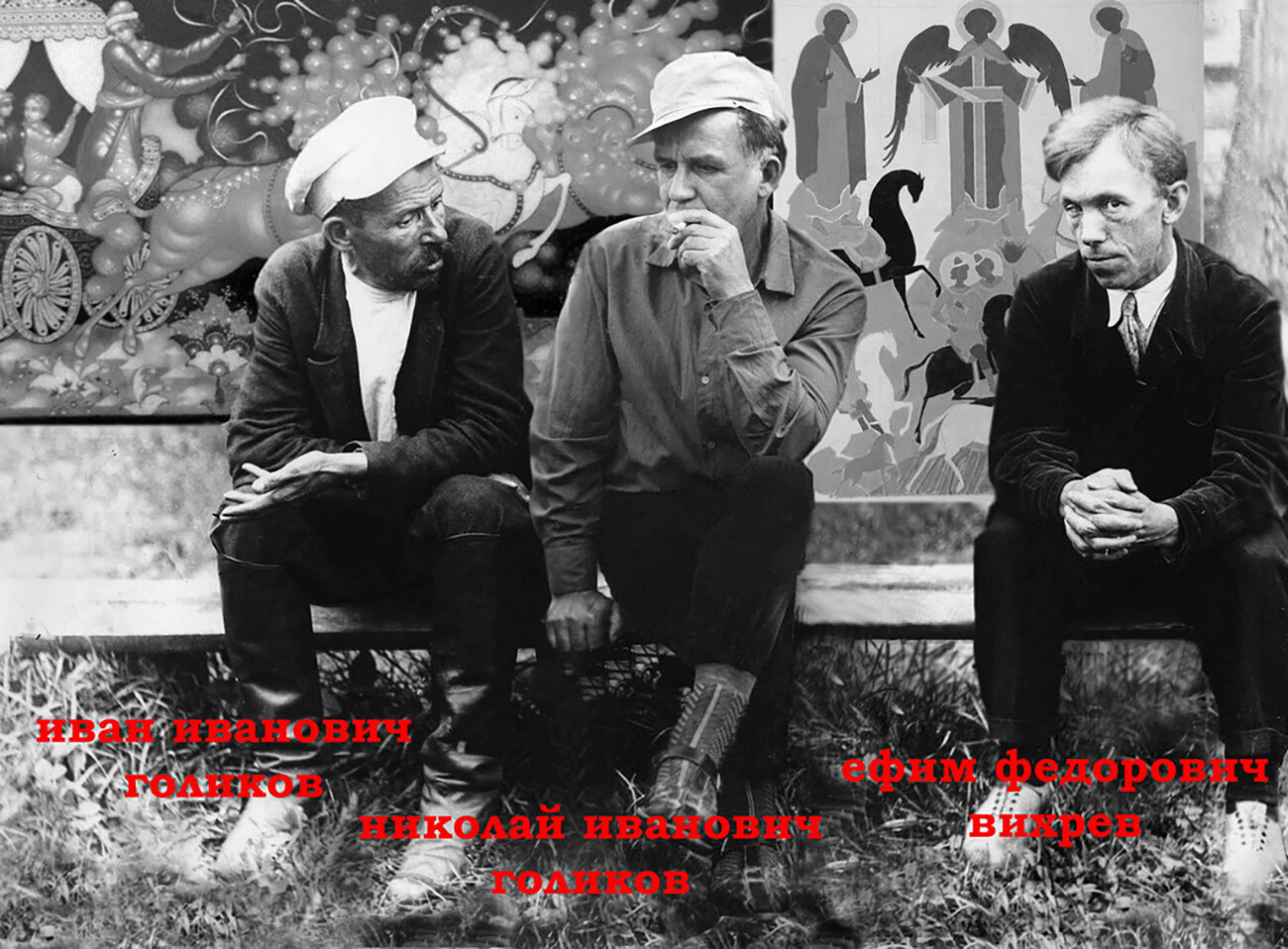

Ivan Golikov first from left

Svetlana Shchirova archiveHis style fascinated the management of the Moscow Decorative Art Museum and art historian Alexander Bakushinsky. With their help, in 1924, he founded the ‘Old Painting Artel’ and examples of the new folk handicraft were sent to international exhibitions in Italy and France.

“After the sensation at Italian exhibitions everything came into motion. The state was managing the whole process and became the client, but almost everything was sold to America – 99% of miniatures were exported, taking into account the preferences of foreigners. The themes were Russian, narratives were from fairy tales and ‘bylinas’ or sometimes purely Soviet and propagandist,” Svetlana Shchirova says.

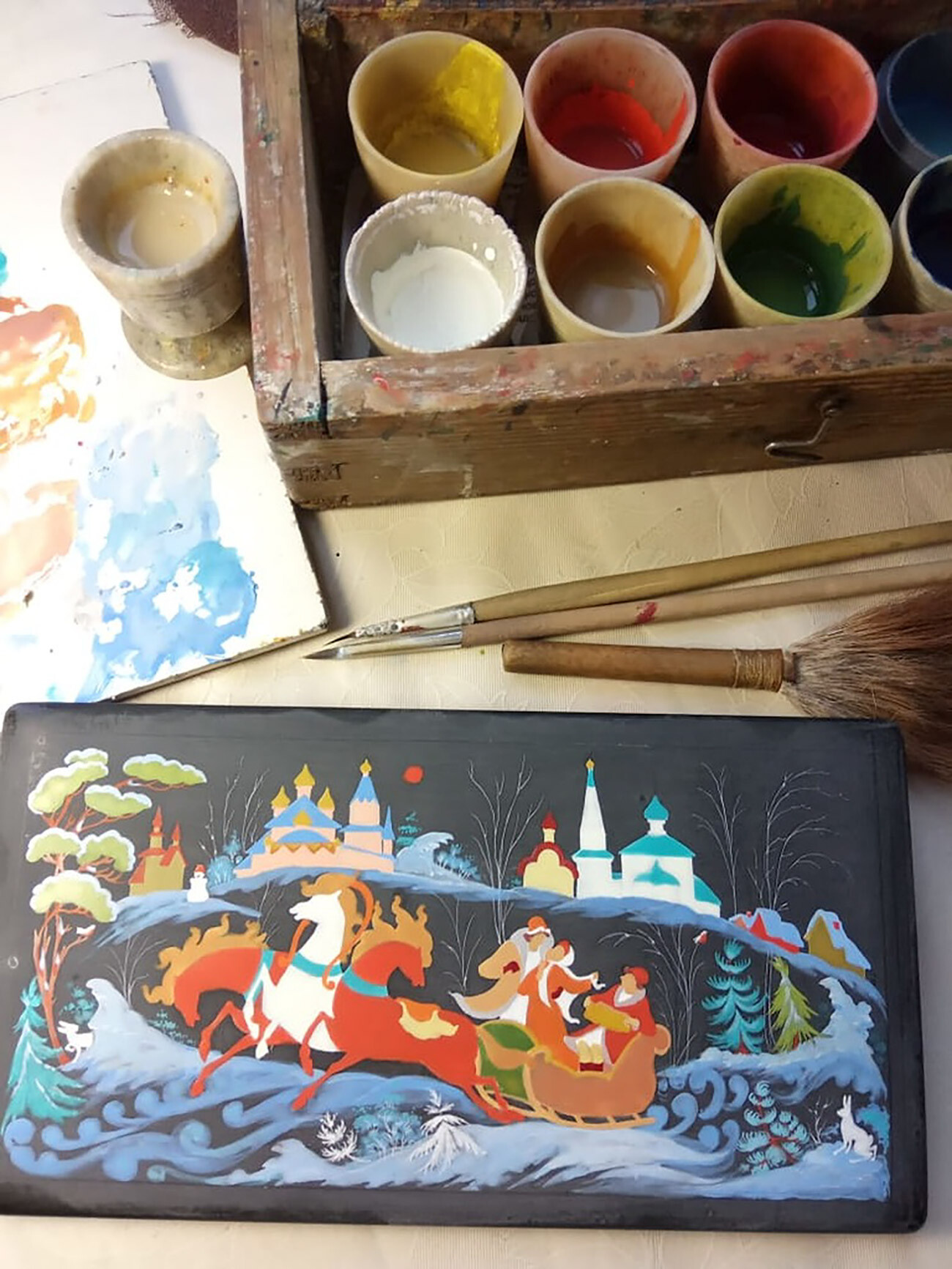

The process of creating a Palekh miniature is complex and labor-intensive. Each piece, be it a box, a brooch, barrettes or a needle case, is small and the painting is very detailed.

Up to half a year is spent on producing papier-mache billets for painting. Cardboard is processed several times: it’s glued, dipped in boiling flax oil, and dried in ovens. In the end, the billet becomes hard “as bone”.

Then it’s puttied; from the inside, the background is then made red, from the outside – black. Then it’s covered with alkyd varnish. For the paints to glow, first comes a white base: the composition is drawn – every finger, hand, eye – then comes the painting itself. After this, it is covered with three layers of lacquer, polished with pumice, painted with gold. The gold is polished with wolf’s fangs or, alternatively, with fox’s fangs, for it to shine. And then – seven more layers of lacquer are added. Every layer is dried in a not-too-hot oven for no less than a full day. Dog’s fangs won’t cut it for polishing,” Shchirova laughs.

5 stages of painting the ‘Winter’ casket by N. Chaparin from whitewashing preparation to the finished work:

1. Whitewash preparation

2. Drawing

3. Detailing

4. Gold application

5. Finished work ‘Winter’ by N.V.Chaparin

The paints are also special, like for icon painting, and they’re called tempera paints. The artists make them themselves, mixing pigments with egg yolk and vinegar water. “The pigment powder is natural, a chemical one would rise to the surface because it’s no good. The yolk should not be fatty, so home-grown eggs won’t do, only store bought ones fit. It’s impossible to paint with heavy paints, as well as with watery ones. Artists determine how heavy paints are just by eyeballing it, from experience, regulating them with vinegar water – earlier they did it with kvass,” Shchirova explains.

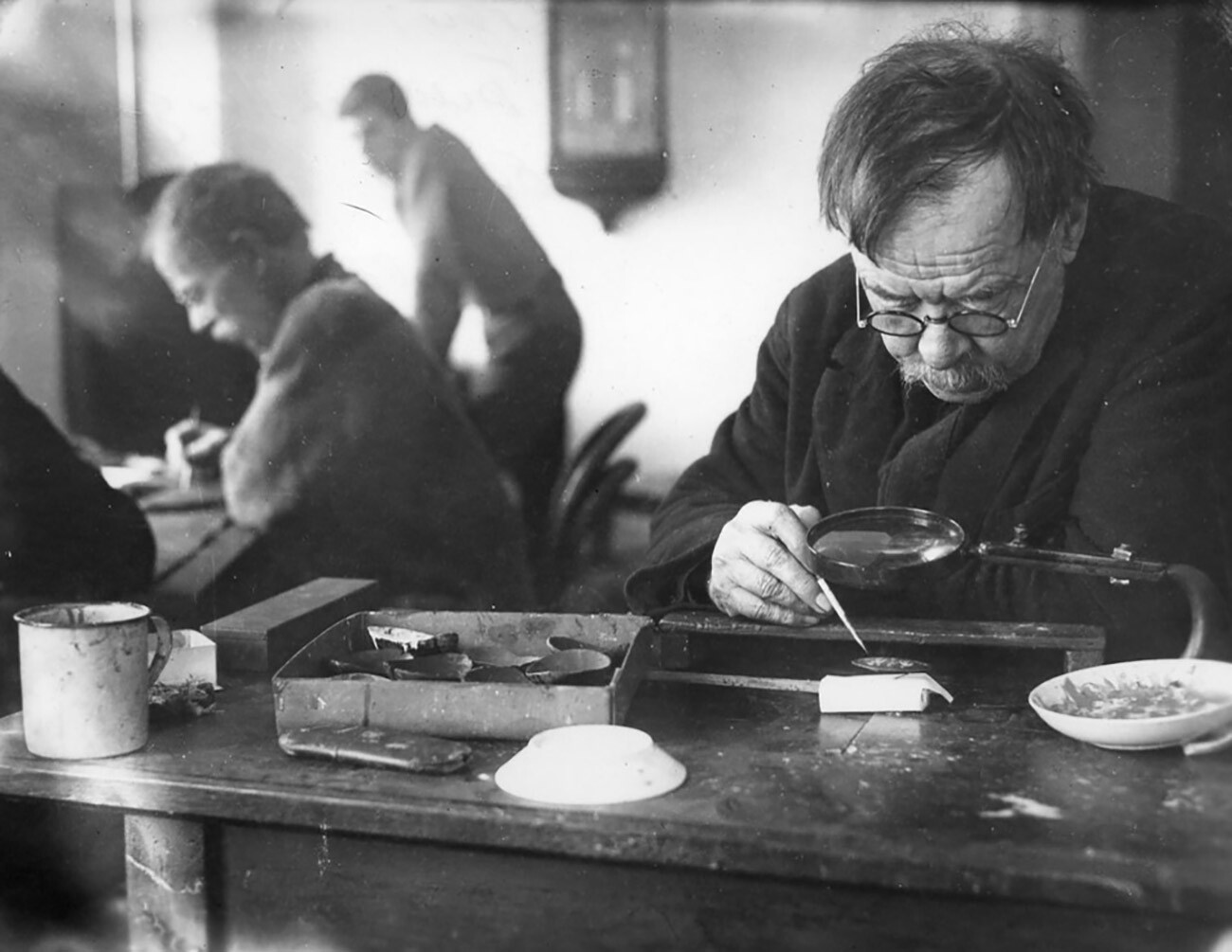

The preparation of gold leaves, with which the painting is covered, also requires effort: gold wire is rolled into the thinnest sheet possible and then glued to the box; or gold is dissolved in gum arabic – the resin of wild Acacia tree. “This is a very complicated process. The finesse of the painting style is in the skill of painting with this dissolved gold. It’s unlikely there are craftsmen like that anywhere else in the world,” the artist says. The paint brushes are still, to this day, only made by the artists themselves – from squirrel tails, as Shchirova says: “The brushes are unlike those from the store – you can only see their tip through a magnifying glass. Such brushes are needed to thinly paint with gold.”

An artist with a magnifying glass

Svetlana Shchirova archiveThe Palekh miniature is distinguished not just by its golden ornaments and strict traditional canons, but also by the thin paint layer technique, which Shchirova describes this way: “If, for example, a fence is green, it’s just green. In Palekh miniature, the green color is glowing and consists of several color tones. For example, there’s yellow underneath that green. Emulsions are thinly applied so the colors are transparent. This complex technique is needed for the play of colors.”

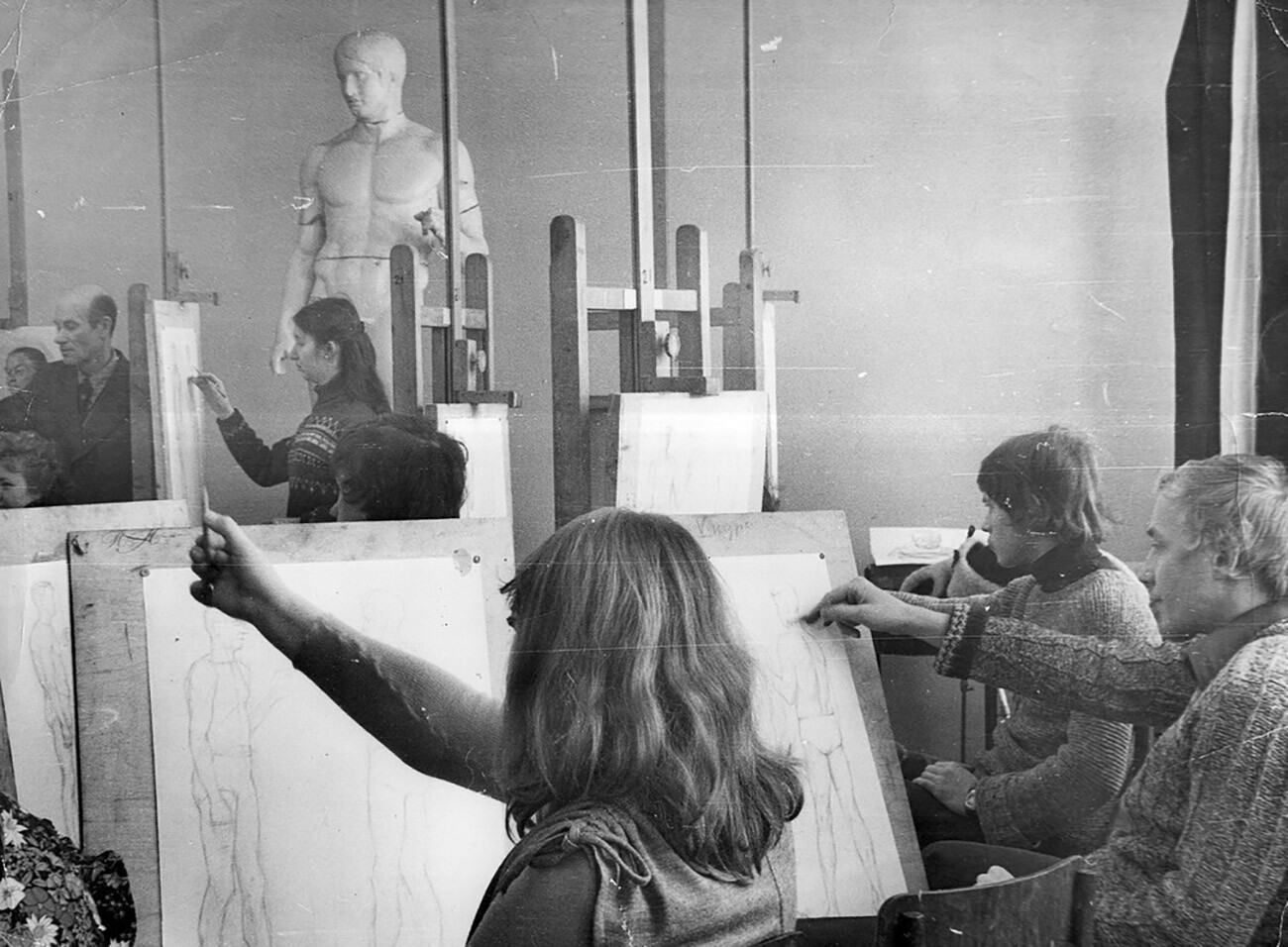

The Palekh Art School

Svetlana Shchirova archiveWith the collapse of the USSR the workshops of the Old Painting Artel were split in two: the Palekh Artists Association and the Palekh Partnership. Their artists still only deal with miniatures; however, the craft found itself on the verge of extinction, despite support from the government and the Palekh Art College that has been operating since the 1930s.

“There’s no continuity,” the head of the Palekh Artists Association, Svetlana Shchirova, states. “Young artists nowadays work at home, they have no opportunity to learn from each other like before. A person graduates from the art college and, only seven years later, realizes why the colors of the painting are glowing like that. I’m 59 years old, not a single one of the children of my peer classmates became a miniature painter. One needs to study long and hard after the art college to produce a good miniature with a hair-thin brush – a miniature that a collector, who appreciates high art, would purchase. And although the art college here was created to teach miniature, it appears it fails to fulfill this function. And it doesn’t foster a love for miniatures.”

Drawing in the art school

Svetlana Shchirova archiveJust like in the USSR, in Russia, the Palekh handicraft, until February 2022, has been working for export: collectors abroad waited for piece products that they deemed pieces of art. Russia doesn’t have many collectors and the handicraft has no souvenir production.

“The Palekh art is very complex and unique: every work is a unique piece, there are no copies. Only the students of the art college make copies when they study. A common person can’t understand this art: why is it so expensive, why are there these motifs, composition, black background? Why are all the figures so stretched? Basically, why did the art traditions shown on the boxes come from icon painting,” Shchirova shares the troubles of the craft.

Old Painting Artel, early 1950s

Svetlana Shchirova archiveShe also adds that one small box can’t cost less than 5,000 rubles, otherwise you know it’s a fake. A miniature is not a loaf of bread – the artist explains – from this 5,000 rubles a craftsman, after paying their taxes, electricity bills and for raw materials, will only have 1,000, while the painting of a box takes a week. A single work can be sold for 100,000 rubles, but that’s the price of an art piece of an honored artist.

Palekh artists

Svetlana Shchirova archive“Our association has workshops; about 50 artists work in them, we gather all the young people, but there’s still only about 10 of them, the age of the rest is on average 65 years. The dynasties are still around: the young from the Palekh families can gain experience from their parents. The others, who, after college, went to work from home, don’t see their mistakes, they can’t put together a composition – that’s the beginning of the handicraft’s demise. After art colleges they go on to paint churches or nails. That brings more money. Churches have a large amount of work and you don’t have to look through two pairs of glasses and a magnifying glass.”

Soviet Palekh association celebrating the 50th anniversary of its work

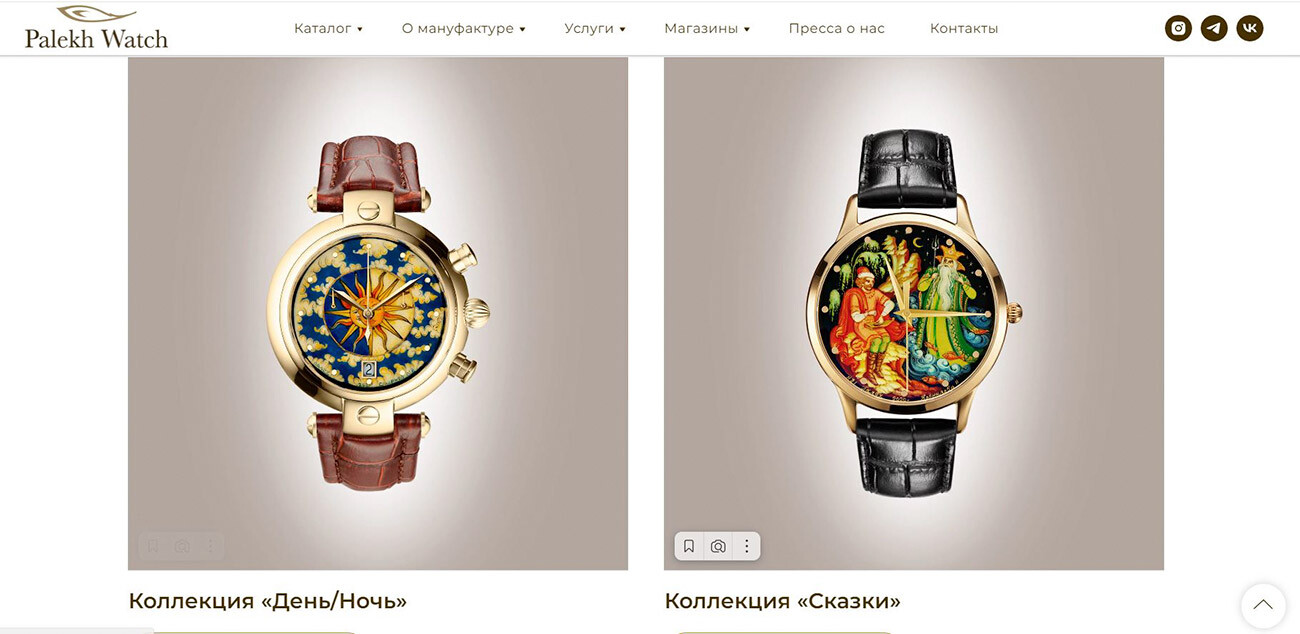

Svetlana Shchirova archiveDespite all the difficulties, Svetlana Shchirova is confident the Palekh lacquer miniature will survive. She talks about how, with the government’s help, Palekh artists started working with the ‘Polyot’ watch factory and painting clock dials in great detail: “This is a miniature of a miniature, even among our artists, not everyone can handle that. Those who are older can’t anymore: the work is too fine, their eyesight doesn’t allow it. Some simply failed at it: only 10 artists are left from twenty. But Palekh can do anything!”

Palekh & Polet watches

Palekh WatchDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox