The painting measures 2.1 x 3.7 meters, and it was Vasily Surikov's first work about Russian history, as well as his first large-scale painting that was publicly displayed. "The arrival of [Surikov's] 'Streltsy Execution' was a sensation in the art world. A statement of that kind had never been made before. He took no time to settle in or adjust – he simply struck with the force of a lightning bolt," recalls Aleksandra Botkina, the daughter of the Tretyakov Gallery founder, Pavel Tretyakov.

The artwork was first exhibited in St. Petersburg at the 9th Peredvizhniki ("Wanderers") exhibition in 1881, and right after that event Tretyakov quickly acquired the painting for his private collection.

The name streltsy literally means "musketeers" in Russian. These professional soldiers appeared in the 16th century during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, and were composed of village and small town volunteers. Only the most able and gifted were admitted - a fact that earned the division an elite status in Russia's regular army. The streltsy were often compared to the Ottoman Empire's elite Janissary infantrymen, as well as the French musketeers.

Service in the streltsy regiment was lifelong and later on became hereditary. They lived apart from others in their own city district (sloboda), and in exchange for their loyalty to the tsar and the State they received payment in money, as well as all kinds of privileges – free bread and cloth, as well as court and tax privileges. They were easily recognized by their impressive uniforms that included a kaftan and hat with fur trimming, as well as the right to carry firearms.

They participated in many military campaigns as a part of the infantry – starting with the campaign against the Kazan Khanate in 1552, and until the Great Northern War of 1700-1721. At the same time, however, they earned a reputation for crushing popular revolts. Under Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich their position was the most privileged. They were considered the main bastion of the old order, but everything changed under Peter the Great.

At the end of the 17th century popular revolts were common, in large part because of the reforms of Peter the Great that often were radical and harsh, and which impacted all segments of society. The streltsy were not an exception.

Their pay at the time was quite meager. Peter's reforms that called for the entire Europeanization of the country only made life more difficult and oppressive for the streltsy. Foreign colonels were put in command, and the streltsy found them tyrannical and despised them, especially because they withheld the men’s pay. In addition, the new regiments that Peter had according to European models were considered elite troops, while the streltsy were now viewed merely as city police.

The streltsy filed an official complaint, a so-called chelobitnaya, to the upper echelons of power, in which they threatened to take action against their superiors if their problems weren’t addressed. But those issues were never resolved. In 1698, while Peter the Great was in Europe, four streltsy regiments (about 2,200 people) mutinied, but they were quickly stopped and suppressed by Peter’s new and highly loyal regiments.

The tsar reacted brutally to the mutiny. He took it not as a socio-economic protest but as a coup attempt, orchestrated by his sister and former regent Tsarevna Sophia. Peter believed that she was the one who persuaded the streltsy to mutiny. So, he decided to punish them severely and participated in the tortures himself, extracting testimonies against the hated Sophia. After facing horrendous torture, 799 of the streltsy were publicly executed. Some – in Moscow on Red Square.

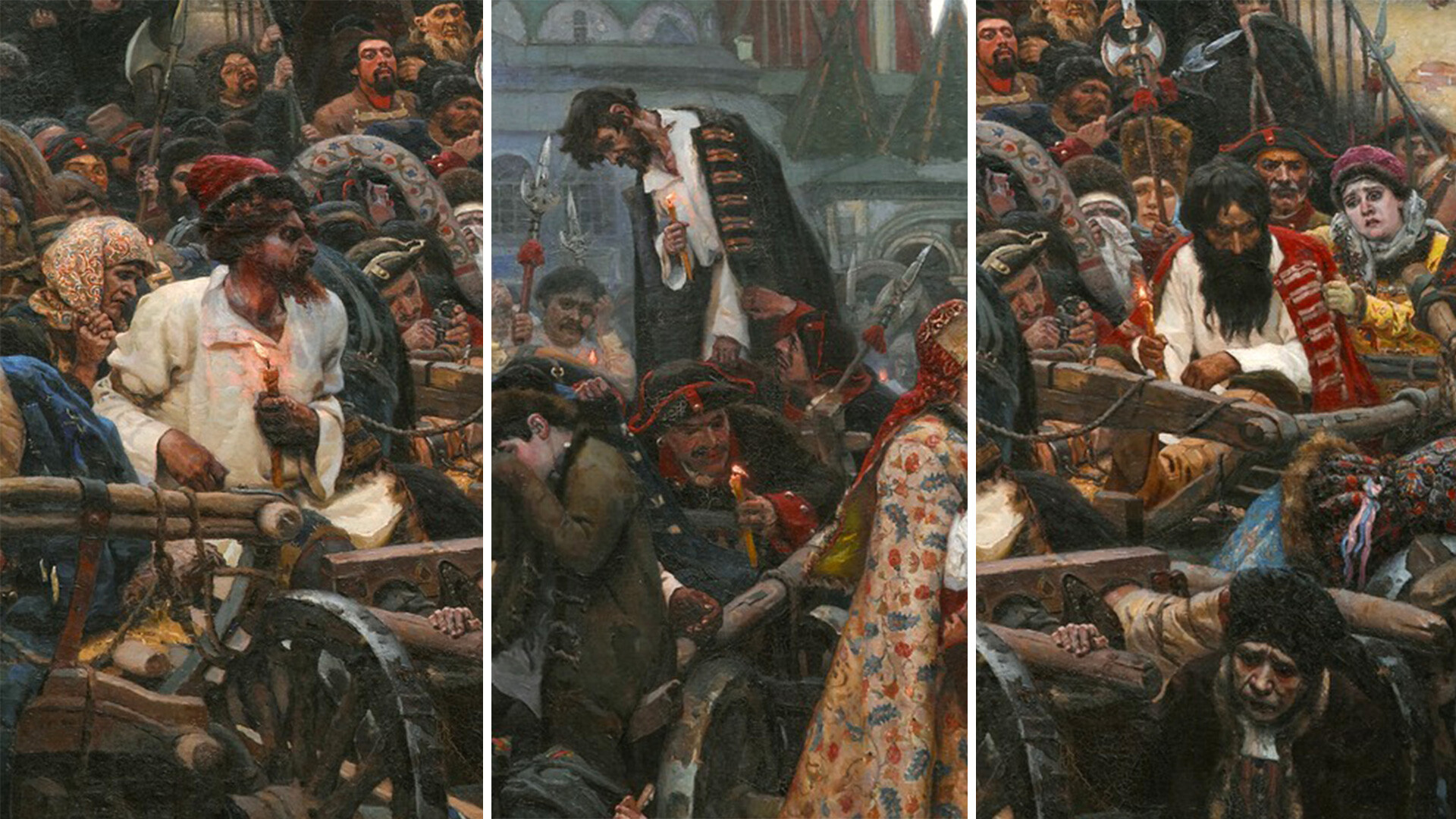

Surikov painted an early morning before the streltsy execution in the fall of 1698. The events take place on Red Square in Moscow. We see how the convicted are taken to Lobnoye Mesto, where gallows have been erected along the Kremlin wall. A motley and dispersed crowd – composed of streltsy (they are dressed in white "death" shirts), their families, and common bystanders – is set against the evenly arranged rows of the new regimental guards and the emperor himself.

"No blood is depicted in my painting, and the execution hasn't started yet," Surikov said. The painter deliberately didn't depict a single hanged man in order to not divert attention from the focal point: the solemnity of the historical execution. In fact, along with the life of these mutineers, an entire era was coming to an end - that of Old Rus'. It was replaced by a State built according to the European model.

Historical narrative paintings were popular in the 19th century, but they were usually painted in an academic manner: solemn and pompous. Surikov was an opponent of such academicism and advocated for realism, which distinguished him from most other painters of his time.

While working on this painting, Surikov scrutinized the old-style clothing and the details of life during the late 17th century. He spoke with historians and read the diaries of contemporaries who witnessed these events. In particular, to portray the atmosphere of 200-year-old reality with meticulous accuracy, the painter referred to the diary of Johann Korb, the secretary of the Austrian envoy who witnessed the streltsy execution. As for the tsar, Surikov painted him based on his portrait. He found live models for everyone else.

An important detail is the lit candles in the hands of the streltsy. As the painter admitted, this image - a lit candle during the day - is associated with tragedy, death, and hopelessness (only memorial candles are lit at funerals that are held during the day). He carried this image within him for many years until he brought it to life in this painting. "I wanted these flames to glow... for that, I gave the main tone of the painting a dirty hue," he wrote. The lit candles in the morning is precisely what instilled anxiety in the audience.

Also, one very peculiar feature of the painting is that it has very little free space; the crowd takes up almost 80% of the space on the canvas, and because of this, the painting appears astonishingly chaotic. However, in fact, the crowd is the main character. Surikov referred to art of this kind as "choral". On the left, the mass of people is "crowned" by St. Basil's Cathedral, symbolizing the image of Old Rus. On the right, there is an even row of soldiers and the tsar, personifying harsh discipline and the State. This division between society and the State in the painting is emphasized by the duel of gazes between Peter and a ginger-bearded strelets.

At the same time, an incredibly important aspect is the strelets heading to his execution and a soldier in uniform who supports him by the shoulder. As art historian Ilya Doronchenkov points out, if we take these people out of the painting's context, we might think they are both pals who are returning home, where one warmly and friendly supports the other. This feeling of two people, forced apart by the will of history yet remaining united, is "an astonishing quality of Surikov's painting."

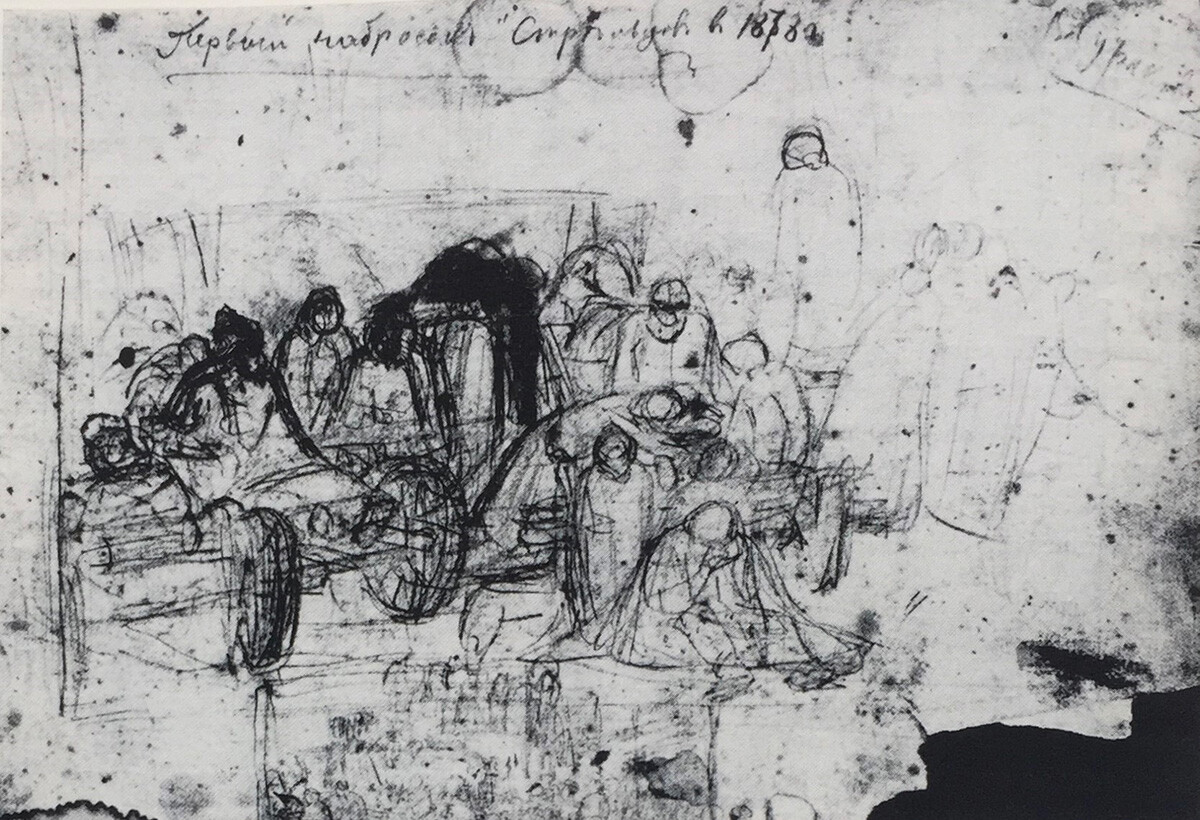

According to the painter, he first thought of the streltsy theme when he traveled to St. Petersburg from Siberia, his birthplace. However, only when he arrived in Moscow and went to Red Square did all the images appear before him in the most minute detail: "I stopped not far from Lobnoye Mesto, lingered to admire the silhouette of St. Basil's Cathedral, and suddenly the scene of the streltsy execution flared up before my eyes, so vividly that my heart started beating faster. I felt that if I painted what I had just seen, it would be an amazing painting."

Surikov spent three years painting that fateful day of execution and wouldn’t allow himself to be distracted by other topics. He worked where he lived, in a small apartment on Zubovsky Boulevard. The painting stood almost diagonally in a small room with low windows, such that when Surikov painted one part of the canvas he couldn't see the other. To view the painting in its entirety, he had to look at it from another room. At night, he would dream of executions, deeply troubled by what he was painting.

The painting received much praise from critics, which inspired the painter to further explore the dramatic events of Russian history. After that, in the 1880s, he painted two more monumental canvases that are sometimes considered part of the artist's historic trilogy: ”Menshikov in Beryozovo” (1883) and “Boyarina Morozova” (1887). We discussed the latter in detail here.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox