This Russian artist turns embroidery into STREET ART (PHOTOS)

Alexander Braulov is a successful artist with personal exhibitions, as well as a ‘Rosneft’ analyst and co-owner of the ‘52factory’ design studio. He “embroiders” Soviet buildings, the memories of his own childhood, scenes from Russian movies and simple phrases familiar to everyone.

He made his first embroidery in kindergarten

Alexander, in an interview with ‘The Art Newspaper Russia’, said that he tried embroidery for the first time back in kindergarten – his group was taught contour embroidery. For many years, he didn’t return to this art, until, during the third-fourth year of university, he tried to embroider again, simply because he lacked some creativity in his life.

Later, Alexander, together with his future wife, started to engage in mail art – sending artistic letters or items by post or creating an art object from the letter itself. The artist then created his mail art project titled ‘150 embroidered faces’. That’s how embroidery came back into his life.

Avant-garde heritage and Russian cinema

One of the frequent narratives in Alexander’s works – Soviet architectural modernism. Embroidering Soviet buildings, the artist tries to carry over the idea of their value and the necessity of preserving unique buildings. Currently, the artist has about 240 such works.

Aviator’s House in Moscow. Built in 1973-1978.

Aviator’s House in Moscow. Built in 1973-1978.

Left photo: GES-2 power station in Moscow. Built in 1905-1907, reconstructed in 2021 and turned into an art space.

Left photo: GES-2 power station in Moscow. Built in 1905-1907, reconstructed in 2021 and turned into an art space.

Another recurrent theme in his works – Russian cinema. Alexander embroiders vivid moments from modern Russian movies.

"You’ll change nothing

Do like everyone else does".

Film In Limbo, 2021. Directed by Alexander Khant. This is the story of two teenagers’ protest against learned helplessness that ends in tragedy.

"You’ll change nothing

Do like everyone else does".

Film In Limbo, 2021. Directed by Alexander Khant. This is the story of two teenagers’ protest against learned helplessness that ends in tragedy.

Film Leviathan, 2014. Directed by Andrey Zvyagintsev. This is a social drama about the conflict between unjust power and a powerless man with references to the Bible.

Film Leviathan, 2014. Directed by Andrey Zvyagintsev. This is a social drama about the conflict between unjust power and a powerless man with references to the Bible.

Documentary embroidery

Alexander also puts this hashtag under his works about everyday life: a grandma buying some groceries, a girl swinging on a swing, children sitting on a sled near a snowman.

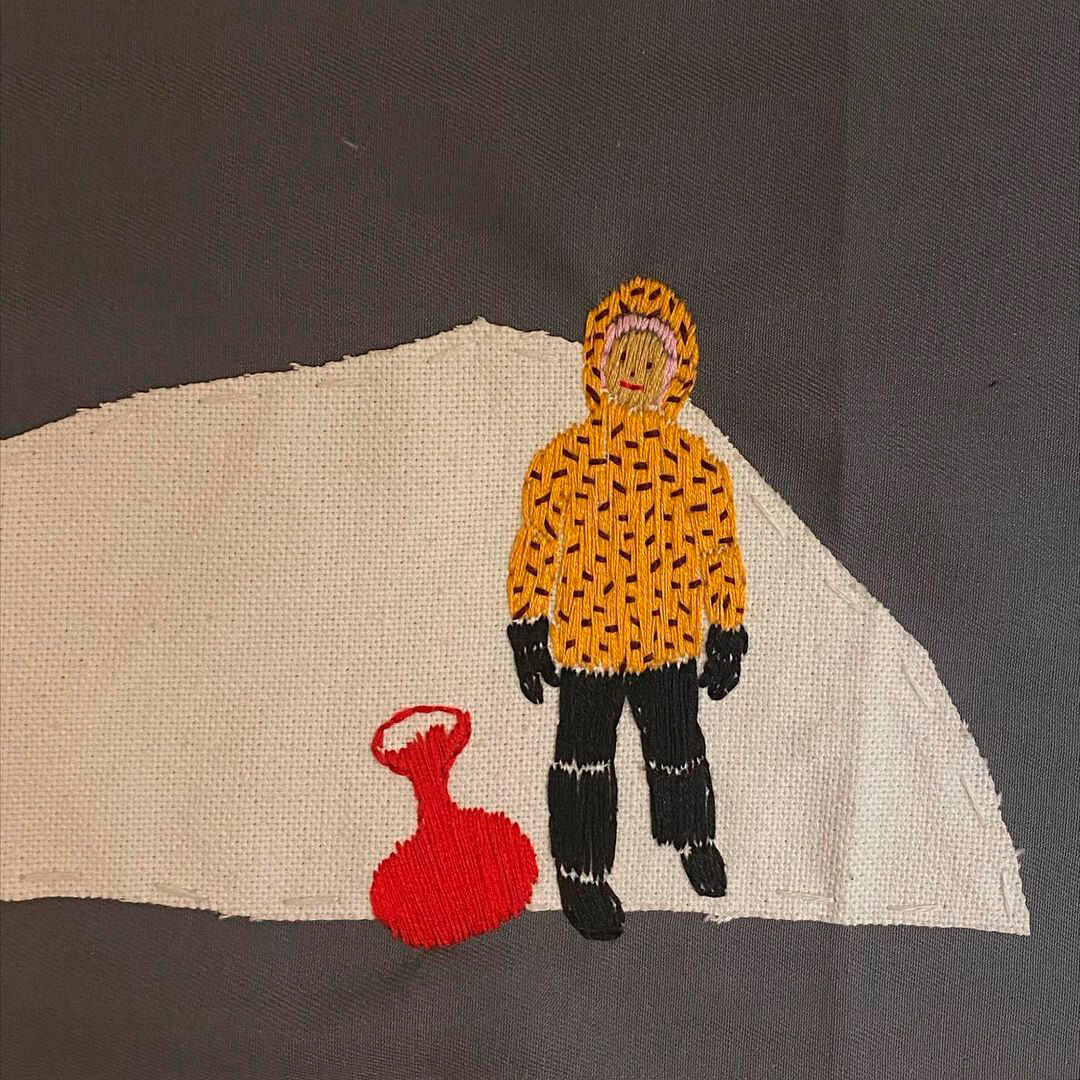

A lot of works of the artist are dedicated to children and that’s not just an attempt to evoke nostalgic feelings in the viewer. Alexander purposefully picks good-hearted and naive narratives to create an impression that the embroidery was made by his six-year-old self.

The red thing next to the kid is a snow saucer, a round piece of plastic with a handle – the simplest device to sled down an icy hill after just a piece of cardboard.

The red thing next to the kid is a snow saucer, a round piece of plastic with a handle – the simplest device to sled down an icy hill after just a piece of cardboard.

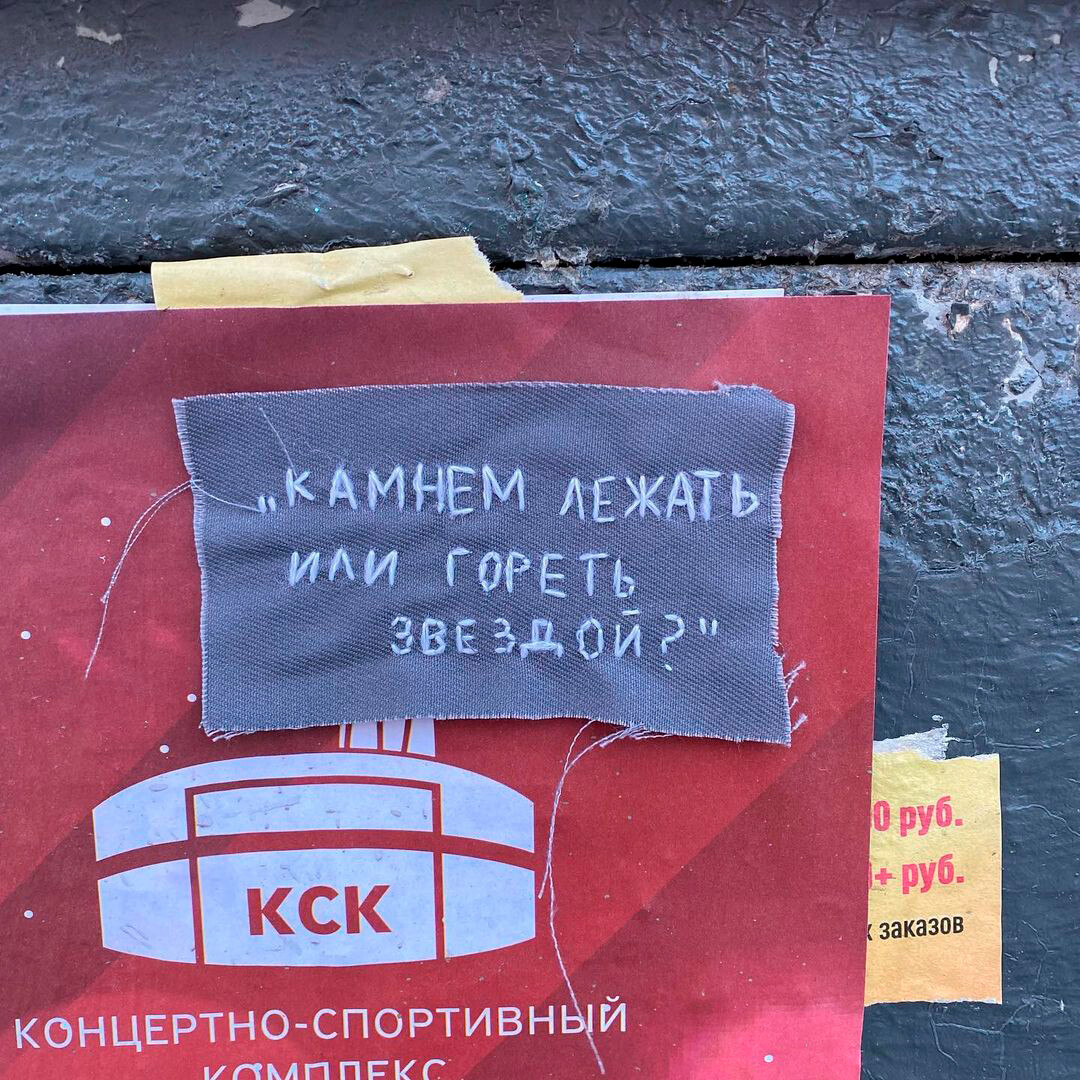

Embroidery on the streets

Alexander often displays his works on the streets of Kolomna, a district in St. Petersburg. Not to damage the buildings, he tries to put up his works only over old advertisements and posters. Usually, the artist picks positive images to put on walls – with mood-raising narratives or famous quotes from Soviet cartoons, songs and poems.

"Do the good and throw it in the water".

A quote from the Soviet cartoon Wow! A Talking Fish!, 1983. Directed by Robert Sahakyants.

The main leitmotif of the cartoon, expressed in the quote, calls for unconditional help and kindness – just because every human can be kind.

"Do the good and throw it in the water".

A quote from the Soviet cartoon Wow! A Talking Fish!, 1983. Directed by Robert Sahakyants.

The main leitmotif of the cartoon, expressed in the quote, calls for unconditional help and kindness – just because every human can be kind.

"Don’t be a fool! Be something others weren’t".

A quote from Joseph Brodsky’s poem Don’t Leave The Room, 1970. Brodsky was a famous Soviet poet and a Nobel laureate, expelled from the USSR.

"Don’t be a fool! Be something others weren’t".

A quote from Joseph Brodsky’s poem Don’t Leave The Room, 1970. Brodsky was a famous Soviet poet and a Nobel laureate, expelled from the USSR.

“Lie as a stone or burn like a star?”

A quote from Viktor Tsoi’s “Cuckoo” song, 1991. Everyone in Russia knows rock-musician Viktor Tsoi. The songs of his band, Kino, are still iconic. His texts always very piercingly speak of the meaning of human life and its hardships in this world.

“Lie as a stone or burn like a star?”

A quote from Viktor Tsoi’s “Cuckoo” song, 1991. Everyone in Russia knows rock-musician Viktor Tsoi. The songs of his band, Kino, are still iconic. His texts always very piercingly speak of the meaning of human life and its hardships in this world.

Also, Alexander is not at all against other people taking the embroidery, should they find it. It wouldn’t stay on the streets for long, anyway – in such conditions, threads quickly fade and tear.

Large format

Not all of Alexander’s embroideries are small. He has large works, as well: ‘Be strong and kind’ (2.5*1.45 meters) and ‘Fear nothing’ (1.4*2.4 meters).

"Be strong and kind".

"Be strong and kind".

"Fear nothing".

"Fear nothing".