"Why don't we have a shot at William, our Shakespeare?" This question, posed by the director of an amateur theater in the cult Soviet comedy Beware of the Car, has become a popular catchphrase. It fully reflects Russian attitudes to Shakespeare. He’s more than a favorite author, poet and playwright rolled into one. He’s one of us, he’s "ours".

It was easier for Russians to read Shakespeare than for the British, because his work came to the country in translation. Shakespeare was rendered into the modern Russian language by skilled translators who themselves had literary talent. It was therefore much easier for Russians to read Shakespeare in Russian than for the English to read him in the original, for which they had to struggle through a labyrinth of archaic English words and syntax.

The effusive love affair in Russia with the Bard, as he is known in England, started at the beginning of the 19th century with a general wave of anglomania. In a short period of time, there were numerous translations of Shakespeare's works, and Russian authors themselves were totally blown away by the English playwright.

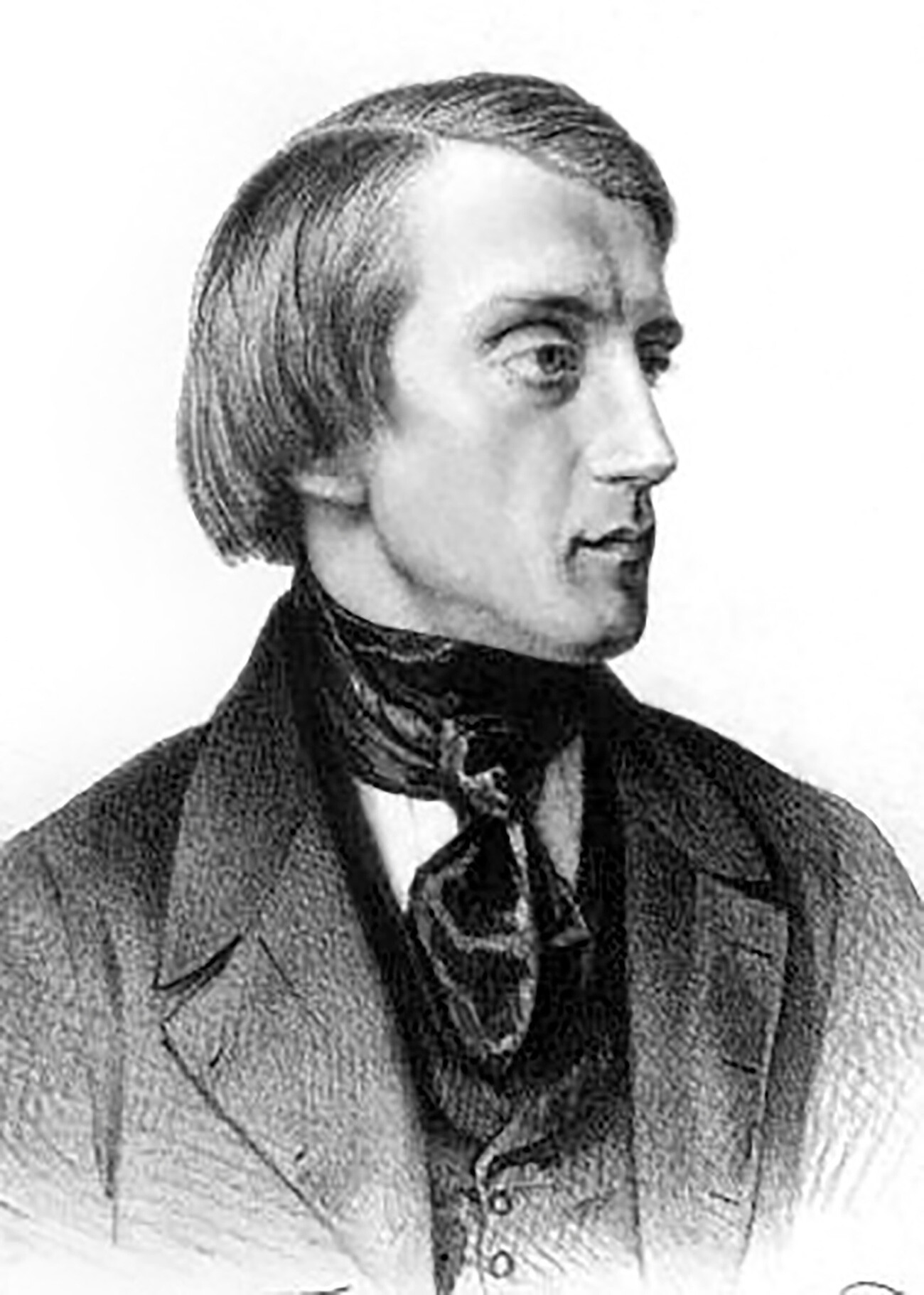

Early 19th century contemporaries said that the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was enthralled with Shakespeare. “Reading Shakespeare leaves my head spinning. It's as if I am looking into an abyss… What a man this Shakespeare was!" Pushkin wrote to his friend Nikolay Raevsky in 1825. "I still can't recover. By contrast, how trivial is Byron the tragedian!"

Pushkin, who was basically raised on French dramas, was struck by the fact that Shakespeare didn't write according to accepted canons, and he admired the "life-like naturalness" of the language of Shakespeare's characters. In Eugene Onegin Pushkin even inserted a direct quote in English from Hamlet: "Poor Yorick!" Lensky says at the cemetery.

"The characters created by Shakespeare are not like Molière's - who are types personifying a particular passion or vice - but real human beings full of numerous passions and numerous vices; and circumstances show the viewer the development of their varied and multifaceted personalities. With Molière, the Miser is miserly and nothing more, while Shakespeare's Shylock (The Merchant of Venice) is miserly, shrewd, vindictive, an affectionate father, witty…" wrote Pushkin.

Pushkin admitted that Shakespeare had had a huge influence on him and, in particular, on his tragedy Boris Godunov, a highly acclaimed work of Russian literature. Moving away from the classical canons of French drama, Pushkin structured his tragedy "according to the manner of our father Shakespeare". In following the Bard's example, Pushkin said, "I confined myself to depicting the era and the historical figures without chasing after stage effects or romantic pathos", and he admitted that he had "imitated him in his free and broad portrayal of characters, and loose and simple depiction of character types."

"Shakespeare's every character is a real human being who has nothing abstract about them but appears to be taken bodily from everyday life, warts and all," wrote Vissarion Belinsky, a prominent 19th century Russian literary critic and theorist, in his article "Hamlet".

In particular, Belinsky explained how Shakespeare's work was superior to French drama. With the French, the protagonist is an aggregated image of a single human trait. "The villain had to be an assortment of all possible villainies, and the man of virtue an assortment of all the virtues, and thus to have no personality at all".

“Hamlet represents a whole distinct world of real life, and just look how simple, ordinary and natural this world is for all its singularity and loftiness. And is not the story of mankind itself lofty and singular precisely because it is simple, ordinary and natural?”

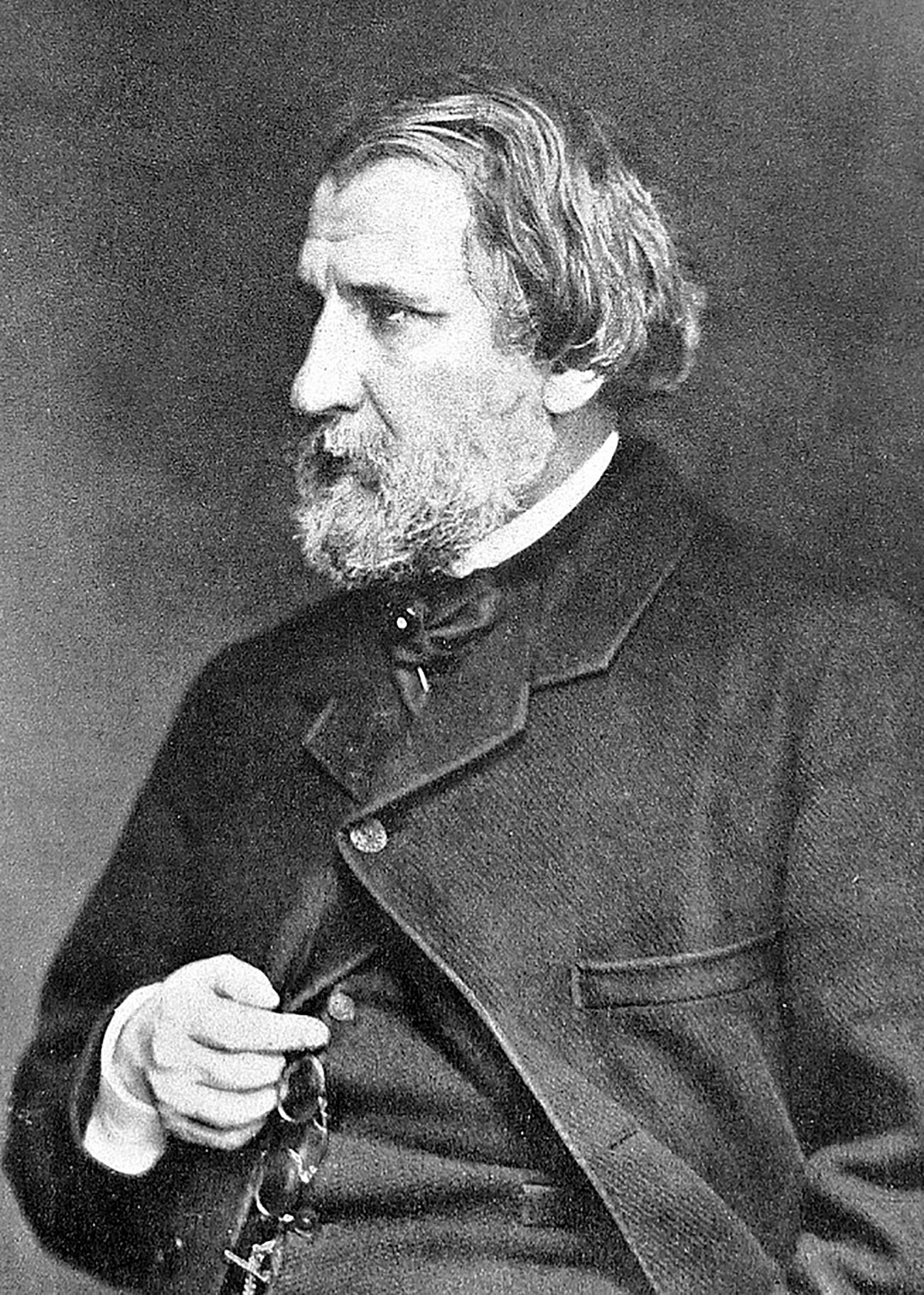

Another prominent Russian writer, Ivan Turgenev, translated Shakespeare extensively. He recognized the Bard's indisputable talent, although he was annoyed by the fact that a whole cult had formed around Shakespeare. As soon as Russian playwrights became acquainted with his work, they started to imitate him and borrow his theatrical effects.

In 1847, Turgenev wrote: "The shadow of Shakespeare weighs heavily on all dramatic writers and they cannot rid themselves of their memories of him; these unfortunates have read too much and lived too little."

Turgenev also was not immune to this. He wrote two works whose titles and subjects contain direct allusions to Shakespeare: A Hamlet of Shchigrovsky District, and A King Lear of the Steppe. Transposed to a Russian provincial setting, both stories lose their lofty and tragic pathos and acquire the hallmarks of farce.

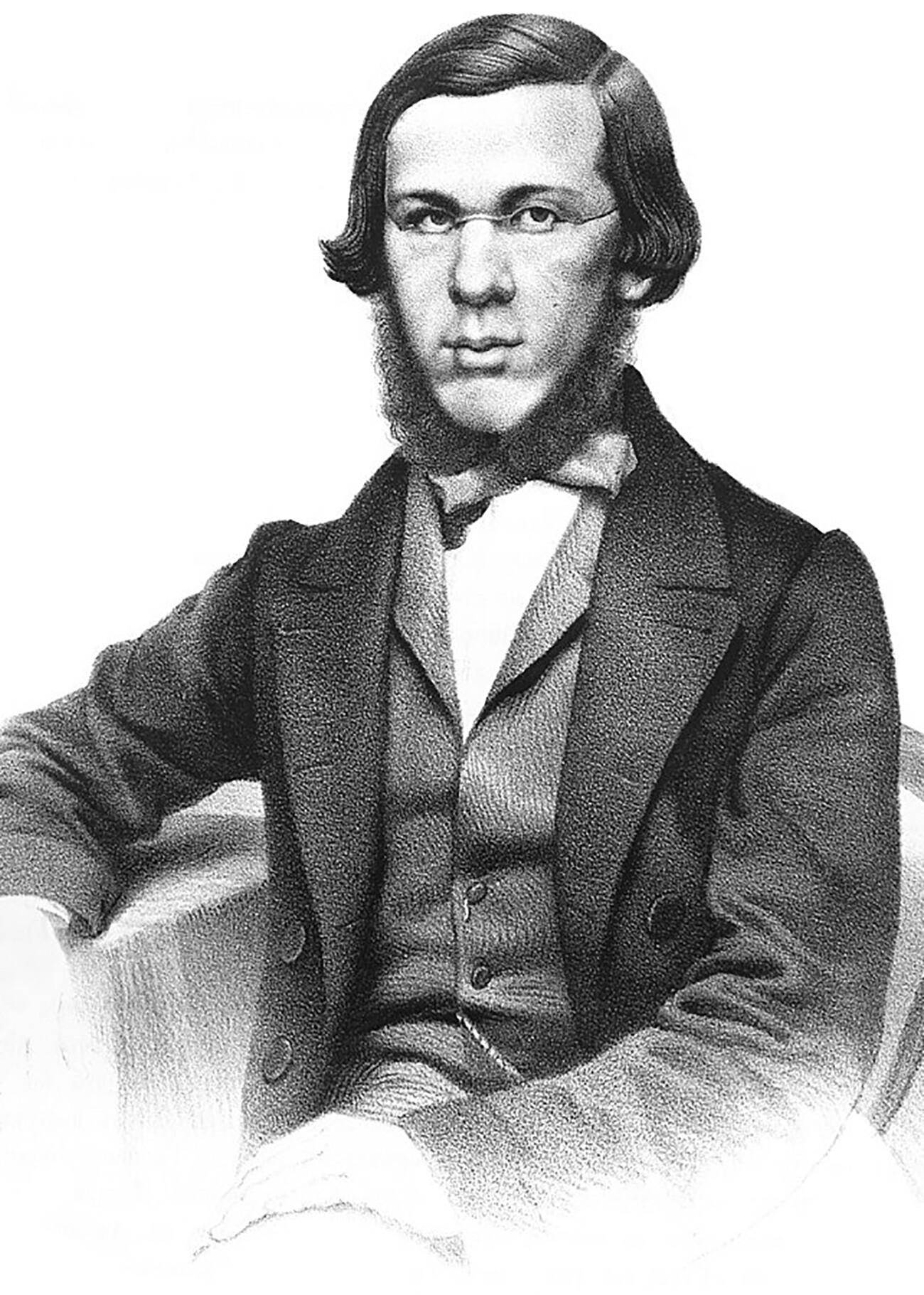

"The truths that philosophers have only conjectured in theory, writers of genius have managed to capture in life and depict in action," wrote another major 19th century literary critic, Nikolay Dobrolyubov, when speaking of Shakespeare.

He put the Bard on the same pedestal as a visionary exerting influence on the whole of mankind, as if seeming to designate new stages of its development.

Dobrolyubov explains why Shakespeare has such universal significance: "Many of his plays can be described as revelations in the realm of the human heart; his literary work advanced people's general awareness by several stages, which no one before him had reached and which only certain philosophers had distantly adumbrated."

"Shakespeare is profound and lucid, reflecting in himself, as in a faithful mirror, the whole of the enormous world and everything that it is to be human," the great writer Nikolai Gogol believed.He said Shakespeare was his literary teacher and had particularly influenced him in the writing of Dead Souls.

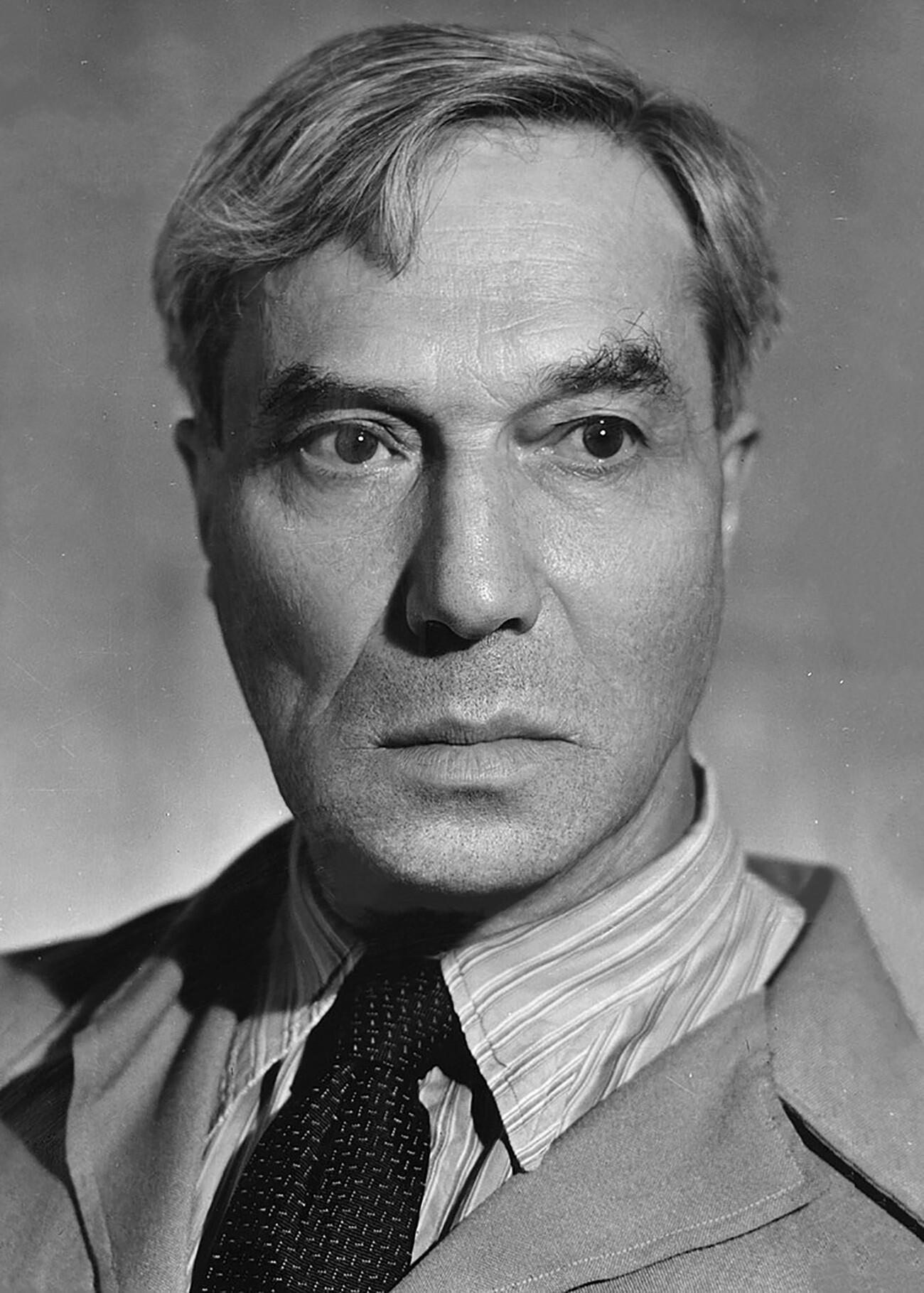

In the 20th century, the outstanding poet and writer Boris Pasternak translated Shakespeare extensively, and the Bard was a major influence on his work. In fact, one of the most important poems in the novel Doctor Zhivago is titled “Hamlet”.

In his article “Remarks on translations of Shakespeare”, Pasternak admitted that the Bard's vivid speech was a mixed bag, sometimes "colloquially natural" and at other times "the loftiest poetry" and rhetoric with an accumulation of semi-articulated allusions.

"Shakespeare was an amalgam of wide stylistic extremes. He combined so many of them that several authors appear to co-exist inside him," Pasternak wrote. Shakespeare's prose, he opined, was accomplished and polished as if written by a "meticulously precise comic writer" of genius. His blank verse, on the other hand, was the complete opposite: its internal and external chaos having "been a source of annoyance for Voltaire and Tolstoy".

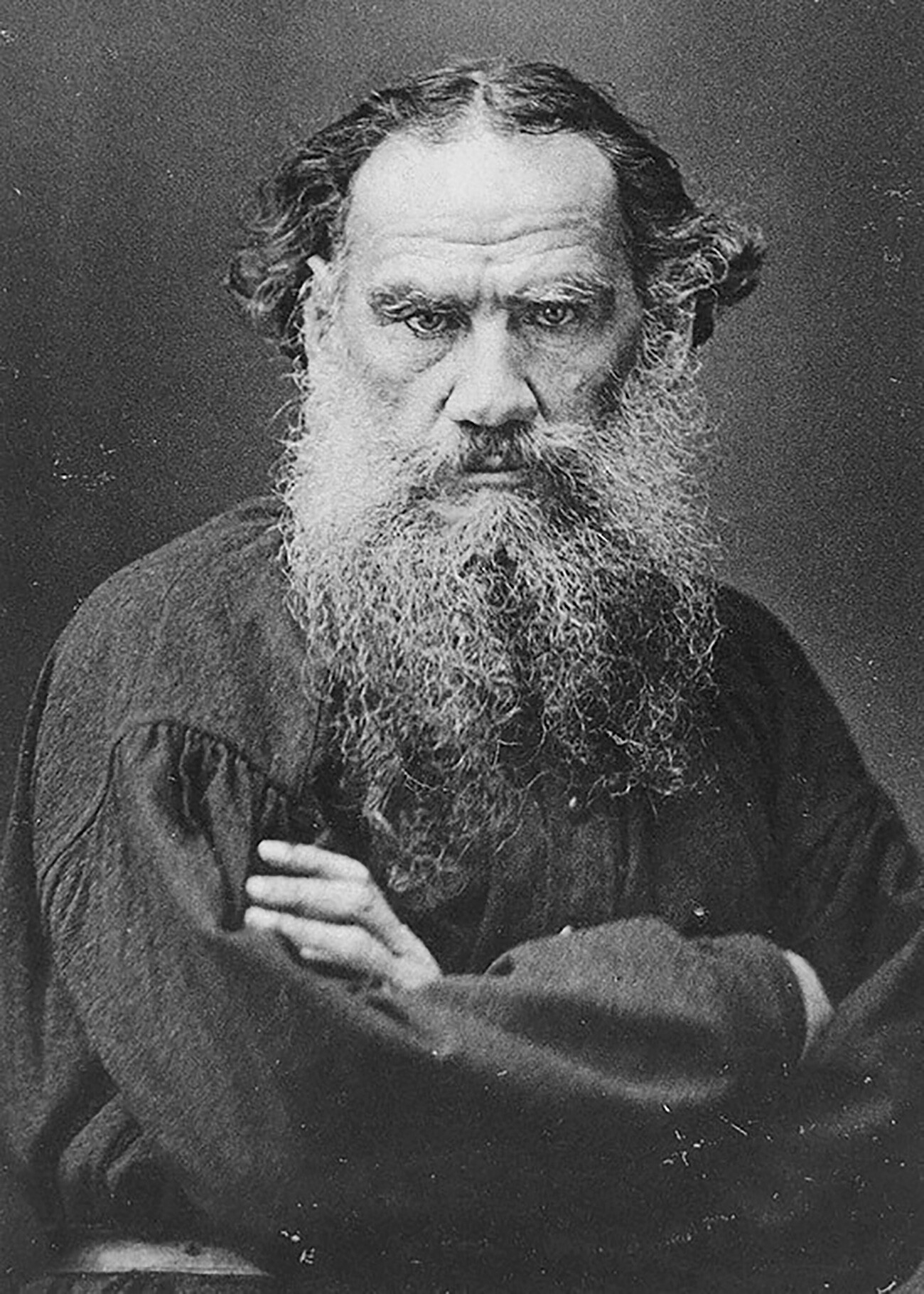

Leo Tolstoy did not recognize society’s established authorities and was highly independent and original in his beliefs. He was the odd man out for his era. The author of Warand Peace was "in utter disagreement with this universal veneration of Shakespeare".

"I recall the surprise I felt when first reading Shakespeare. I had expected to get considerable aesthetic enjoyment…but I felt an overpowering aversion, tedium and bewilderment."

He described KingLear as a preposterous drama and, in a detailed deconstruction of the play, pinpointed a multitude of shortcomings. Tolstoy was primarily unhappy with what he saw as the lack of verisimilitude in the circumstances of the tragedy presented in the play.

Tolstoy described Shakespeare's plays, including Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet and Macbeth, as "worthless and plain bad works". He admitted to having re-read Shakespeare several times in the course of 50 years both in Russian, English and German in a bid to understand him, but each time he had experienced "aversion, tedium and bewilderment".

Tolstoy was repelled by the "immorality" and "vulgarity" of Shakespeare's plays. He branded Shakespeare's language as falsely sentimental and reproached the playwright for his inability to endow his protagonists with a distinctive personality, while Shakespeare's Hamlet seemed completely unconvincing.

"Lovers, those preparing to die, men engaged in battle and the dying are remarkably and unexpectedly voluble on subjects that have nothing to do with the situation they find themselves in," Tolstoy wrote. He also condemned the endless puns and banter, which he found completely unamusing and pointless.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox