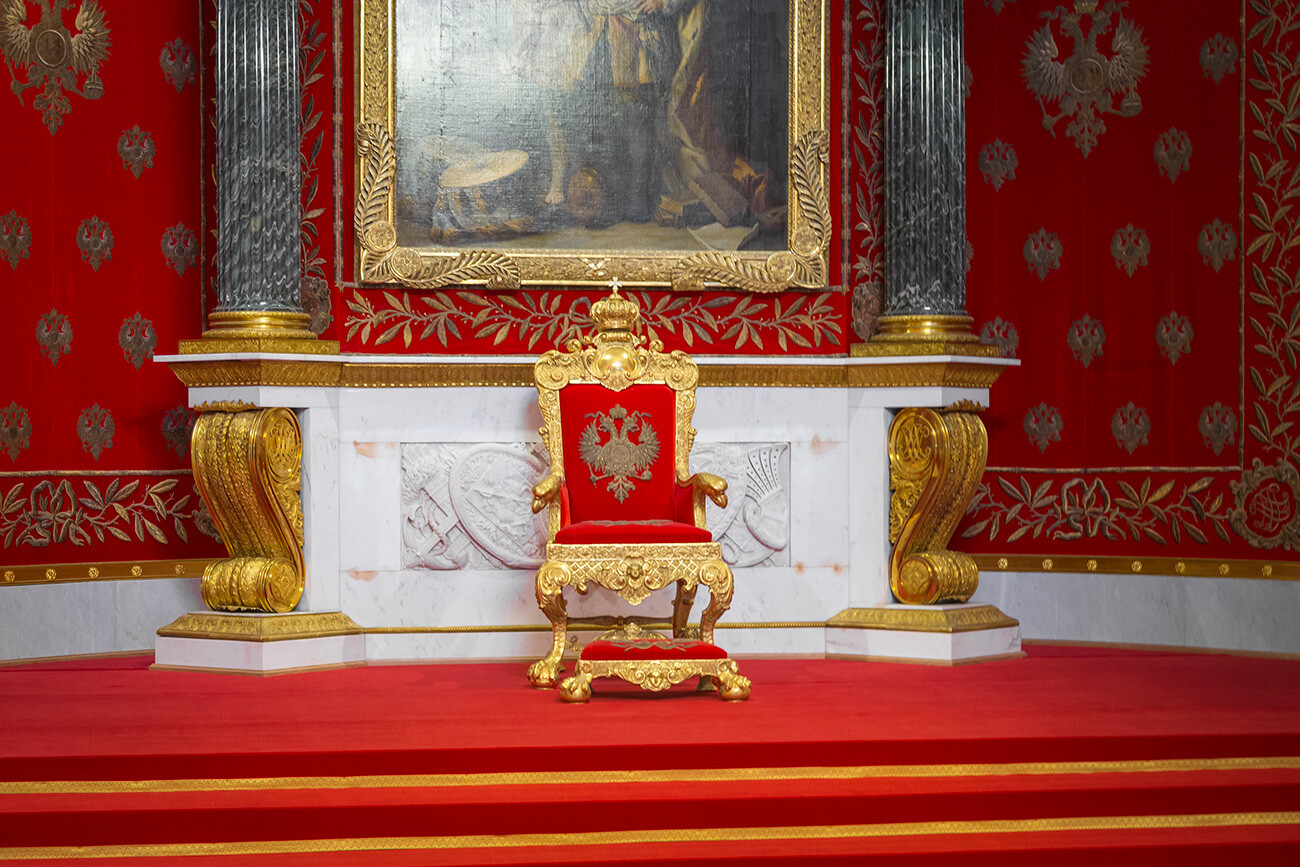

It was created in 1787-1795 according to the project of Giacomo Quarenghi and consecrated on November 23, 1795 – the Day of St. George. The initial interior design was lost in the fire of 1837; it was then restored by architect Vasily Stasov at the beginning of the 1840s.

This, perhaps, is the most ceremonial hall of the Hermitage. It hosted official ceremonies and receptions. Carrara marble and gilded bronze were used in the interior design; the halls’ parquet is made of 16 types of wood. The large imperial throne was made on the commission of Anna Ioannovna in London. Above it, the bas-relief ‘St. George killing the dragon’ is placed – one of the most famous narratives of Russian heraldry.

Created in 1833 by Auguste de Montferrand, the hall also burned down in the fire of 1837. Vasily Stasov was engaged in its restoration.

The hall is dedicated to the memory of Peter the Great. You can see the monogram of the first Russian emperor in the interior (two Latin ‘P’ letters), two-headed eagles and crowns, as well as Jacopo Amigoni’s painting ‘Peter the Great with the Allegorical Figure of Glory’ and other paintings, depicting Peter the Great on the fronts of the Great Northern War, made by Pietro Scotti and Barnaba-Giovanni Medici. The throne, the silver-embroidered panels and silver pieces were made in St. Petersburg at the end of the 18th century.

This is one of the largest ceremonial rooms of the Winter Palace: its area is 1,000 sq. meters. The hall was also designed and decorated by Vasily Stasov in 1839 on the commission of Emperor Nicholas I. The idea of glorification of the might of the Russian Empire became the foundation of its interior.

The entrances to this golden hall are decorated with ancient Russian warriors with banners; shields with the coats of arms of Russian provinces are secured on their poles. The images of the coats of arms of Russian provinces survived on the chandeliers. A vase made of aventurine stands in the middle of the hall.

The idea of creating a grand gallery in honor of the Russian victory in the Patriotic War of 1812 belonged to Alexander I. In 1818-1819, he went to Aachen, Germany, to a Holy Alliance congress, where he met English portraitist George Dawe, who had arrived in the entourage of Edward, Duke of Kent.

The tsar commissioned Dawe to paint a series of portraits of Russian generals – the participants of the 1812, 1813, and 1814 campaigns. During the first year of his work, the painter finished about 80 portraits, then he took on assistants Alexander Polyakov and Vasily Golicke. They mostly dealt with the copies of portraits sent by generals who couldn’t pose in person.

The gallery, designed by Carlo Rossi, was opened in 1826, a year after the death of Alexander I. It was decorated by 332 portraits. In 1837, a fire destroyed the interior of the hall, but all the paintings were miraculously saved. Vasily Stasov later restored the interior of the hall.

This grand parlor, reminiscent of a golden box, was designed by architect Alexander Briullov for the marriage of future emperor Alexander II in 1838-1841. The project was approved by Nicholas I; he took the Throne Room of the Munich Residenz as an example for the design.

The ceiling of the parlor is decorated with a gilded stucco ornament. The curtains, cornices, and furniture upholstery were initially crimson; in the 1960s, during restoration, the textiles were replaced with light blue color.

Initially, this room was called the Jasper Room: in 1830, architect Auguste de Montferrand designed it for Nicholas I’s spouse, Alexandra Feodorovna. The initial interior, too, was lost in the fire of 1837. A grand malachite vase and furniture based on the drawings of de Montferrand were saved, however. Alexander Briullov restored the room in 1838-1839 as the Malachite Room.

From June to October 1917, the Malachite Room even hosted the sessions of the Russian Provisional Government.

This is one of those halls where you don’t know where to look: at the ceiling, the chandeliers, arcades, fountains or the Peacock Clock.

Architect Andrei Stakenschneider decorated this hall in 1855-1858 in the style of Eclecticism, merging in the interior the motifs of Antiquity, Renaissance and the Orient. The abundance of columns and chandeliers, light marble and gilding, lead glass and a mosaic panel on the floor in imitation of Ancient Rome create the feeling of an airy, delicate, ceremonial interior.

One of the most famous pieces of the Hermitage decorates the hall – the Peacock Clock, made in the 1770s by English craftsman James Cox and purchased by Catherine the Great in 1781. This is the only large automaton clock of the 18th century in the world that survives to our day unchanged and operational.

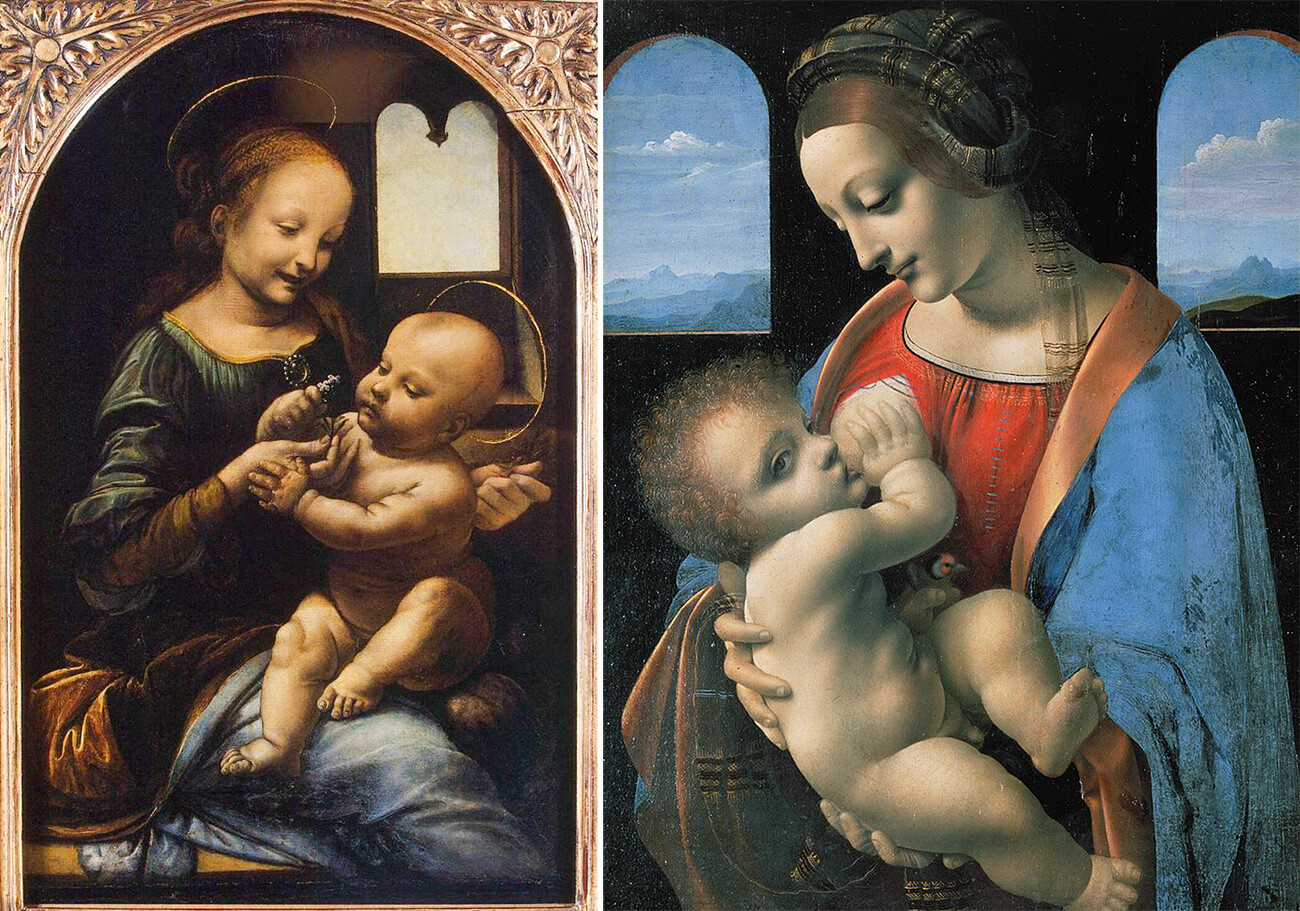

Only two paintings are exhibited in it, but what paintings they are: the ‘Benois Madonna’ and the ‘Madonna Litta’ by Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519). These invaluable paintings were moved to this hall in the middle of the 20th century.

The interior was created by Andrei Stakenschneider in the 1850s in the spirit of the style of Louis XIV.

At some point, this room bore the name of Small Field Marshal Room – in honor of Russian commanders Pyotr Rumyantsev, Grigory Potemkin, Vasily Dolgoruky, Alexander Suvorov, Mikhail Kutuzov, and Ivan Paskevich: their relief images decorate the spaces above the doorways.

In the middle of the 1890s, presents brought by future emperor Nicholas II from the East were stored in it.

The prototype for these loggias was the gallery of the Apostolic Palace in Vatican, painted according to the sketches of Renaissance painter Raphael.

The loggias were designed and built from 1783 to 1792 by architect Giacomo Quarenghi on the commission of Catherine the Great. You can see copies of ‘Raphael’s Bible’ on the vaults of this gallery in the Hermitage – a series of biblical paintings exhibited in the Apostolic Palace.

According to the design of architect Leo von Klenze, the hall for exhibiting antiquity vases was supposed to become one with its exposition. that maintains its function to this day.

Columns separate this space into three galleries; as such, the planning of antiquity temples is replicated. A mosaic from small squares of white, yellow, gray, black and dark red stone decorates the floor. The coffered ceiling is decorated with an ornamental painting. The hall exhibits vases from Etruria and areas of Southern Italy from the end of the 9th – 2nd century B.C.

This is yet another structure you surely can’t miss in the Hermitage – the principal Jordan Staircase, designed by architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli in 1758-1761 in the Baroque style and almost identically restored by Vasily Stasov after the fire of 1837 . A pavilion to sanctify water over the hole that was cut in the ice of the Neva River during the celebration of the Baptism of Jesus was called a ‘jordan’. It was from this staircase that a religious procession would descend to the river.

Two enfilades begin from the Jordan Staircase: the Neva enfilade that leads to the emperor’s personal chambers and the Grand enfilade – towards the Grand Throne (St. George’s) Room and the Grand Church. The ceiling of the staircase is decorated by Gaspare Diziani’s plafond painting ‘Olympus’. This is the largest painting by area in the Hermitage collection.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox