We recently published an article with the provocative title: ‘5 reasons you shouldn’t read Russian literature’. In it, we controversially suggested that classic Russian novels are boring, too wordy, long and disconnected from the modern world.

We intentionally omitted disclaimers about the piece’s ironic nature, playing into an anti-genre we describe as “Bad Advice”, where the context means the exact opposite of what is written. Needless to say, our stance on the value of Russian literature is quite the opposite!

Our readers on our Telegram channel, meanwhile, passionately defended the likes of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Their powerful responses, filled with personal insights and appreciation, highlighted the true value of Russian literature. Below is a summary of their compelling arguments (some direct quotes have been edited for clarity).

A still from 'Idiot' movie, based on Dostoyevsky's novel

Ivan Pyryev/Mosfilm, 1958Oliviana Pandan Nikolai shares her experience of reading Dostoevsky’s ‘The Idiot’ and ‘The Brothers Karamazov’.

“I found both depressing, which had a huge impact on myself, especially my daily life. But, I can cope with that. Life is life. There were ups and downs,” she writes.

A still from 'Anna Karenina'

Alexander Zarkhi/Mosfilm, 1967Xiaolongnü cites a popular meme: "In Russian literature, the character, author and sometimes the reader, suffer. When all three suffer, it becomes a masterpiece.”

Beyond the humor, Xiaolongnü eloquently expresses how these works offer profound insights into the human psyche and experience, urging action against injustice and inspiring moral choices.

One common theme in Russian literature is the depiction of characters in inescapable situations, notes Xiaolongnü. Figures like Onegin and Raskolnikov often feel alienated and superior, but, ultimately, cannot change their circumstances. This literature frequently portrays tragic love stories, such as those of Anna Karenina and Alexey Vronsky, which seldom have happy endings.

A still from 'Eugene Onegin'

Roman Tikhomirov/Lenfilm, 1958“If we can't appreciate it, we are at a loss,” Liza Maciejewski argues. She notes that many people today might lack the mental capacity for such deep emotional and psychological exploration.

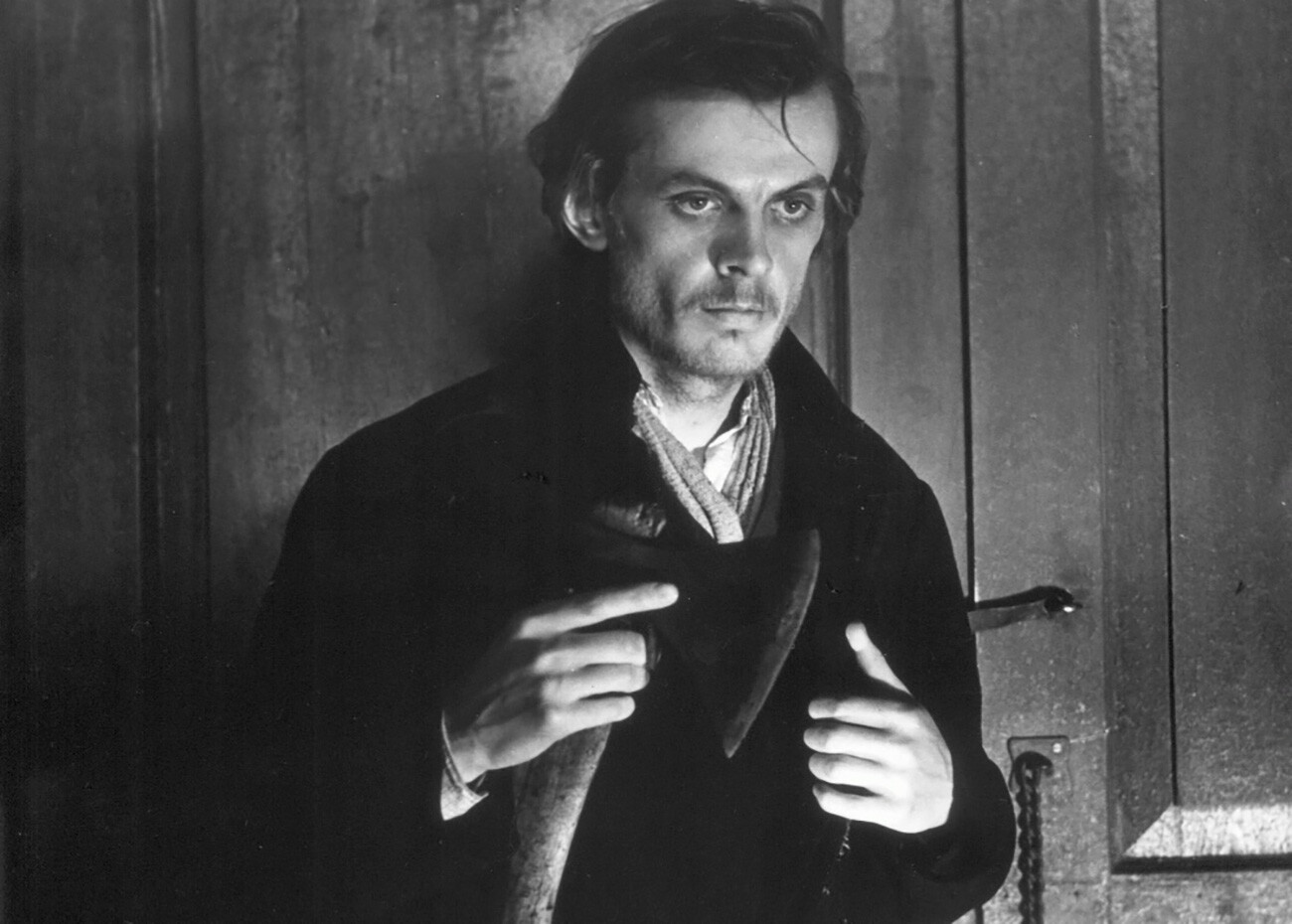

A still from 'Crime and Punishment'

Lev Kulidzhanov/Gorky Film Studio, 1969Peter Byrne, re-reading ‘Crime and Punishment’ after over 50 years, finds it as impactful as ever.

“It’s bloody magnificent. We live such superficial lives, many of us. It’s important to listen to voices that penetrate the psyche and reveal layers of human sensibility that enrich, expand, challenge and perhaps fulfill us,” Peter says.

He believes that such literature reveals universal human truths that transcend cultural and temporal boundaries.

A still from 'The Brothers Karamazov'

Ivan Pyryev, Mikhail Ulyanov, Kirill Lavrov/Mosfilm, 1968Ernest Tomic, meanwhile, points out that classics, in general, are timeless. Yes, there are elements within them that may no longer reflect today's values, but they also serve as windows to the past, offering insights into the thoughts and feelings of people from another era. These works can still be valued for many reasons, not least because they are often well-written and tell compelling stories.

“There are stories in the Bible, for example, which are shocking. Should we therefore delete, change, or censor those passages to accord with current values? I think that would be a very big mistake,” Ernest writes.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox