“A writer well known to the world, Russian by birth, Orthodox by baptism and education, Count Tolstoy <…> has insolently risen against the Lord and His Christ,” the ‘Decree of Excommunication of Tolstoy’ stated. It was published by the Holy Synod (supreme administrative governing body) of the Russian Orthodox Church on February 24, 1901.

According to it, Tolstoy “repudiated the Orthodox Mother Church, which reared and educated him” and devoted his literary activity and talent “disseminating among the people teachings repugnant to Christ and the Church”.

As a result, for “anti-Christian and anti-Church false teaching”, the Synod announced Tolstoy's excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church.

A conversation about religion

A.I. SolomatinBack in the early 1880s, Tolstoy, a deeply religious man, stepped into a period of deep spiritual crisis. He rethought the issues of religion and stopped following the accepted church rituals, believing that true faith does not need such intermediaries as priests and the church.

The main religious works of Tolstoy were the novel ‘Resurrection’, as well as philosophical treatises ‘Confession’ and ‘What I Believe’. In them, he expressed quite daring ideas, for example, the denial of the divine origin of Christ and the miracles he performed.

Tolstoy himself explained that, with his religious teachings and his philosophical articles, he tried to overcome the crisis of faith that occurred in Russian society in the late 19th century. He believed that it was necessary to save faith from the outdated Church and urged people to pray on their own. And Tolstoy had many followers, the so-called ‘Tolstoyans’.

Already in the 1880s, prominent clerics began to polemicize with Tolstoy. John of Kronstadt, one of the most influential priests of that time, called Tolstoy “a heretic who surpassed all the heretics” (Read more about their polemics here).

Leo Tolstoy on his walk from Moscow to Yasnaya Polyana

Public domainThe day after the Synod's decision was issued, it was reprinted by all the newspapers in the Russian Empire. A real scandal had broken out: the most famous Russian writer, a real star of the world, was excommunicated from the Orthodox Church!

Tolstoy himself protested and wrote an answer, saying: “I do not say that my religion is the only one true for all times, but I do not see any other one more simple, clearer, more responding to the requirements of my intellect and my heart. If ever I should learn of such an one I should immediately adopt it, because truth is the only thing God desires.”

At the same time – and this was also what Tolstoy complained about – he wasn't excommunicated in a proper way, according to all church rules. Which actually made this decree legally invalid.

In the past, excommunication was reserved mainly for Old Believers schismatics like Archpriest Avvakum or criminals of the state, such as Grigory Otrepiev (‘False Dmitry’) or rebels like Stepan Razin and Yemelyan Pugachev. Interestingly, from 1869 until the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, no one was excommunicated, as it was considered to be too serious a punishment.

So, officially, Tolstoy was never really excommunicated. The Synod's message was composed in careful terms, not in accordance with all the rules, and Tolstoy was not technically excommunicated, but, rather, had “fallen away” from the Church. It was said that the Church did not reckon him as its member, like a kind of prodigal son. At the end of the decree, the Synod stated that the Church would pray that God would send Tolstoy repentance and turn him back to the holy Church.

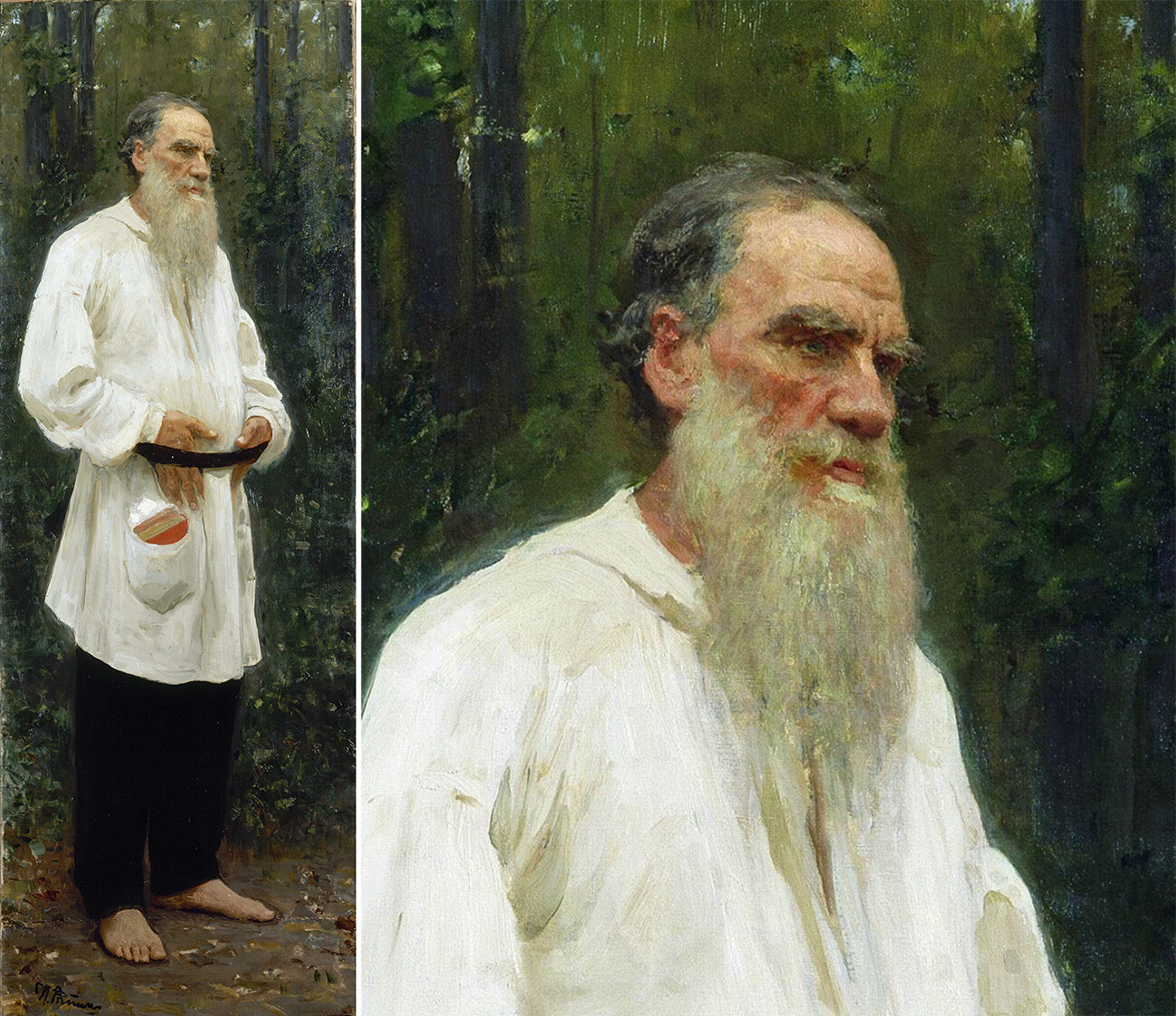

Ilya Repin. Leo Tolstoy Barefoot, 1901

State Russian MuseumAt that time in Russia, Tolstoy's moral authority and popularity in the educated secular milieu was much higher than that of the Church. According to Tolstoy expert Pavel Basinsky, the public, which adored Tolstoy, laughed at the Synod's Decree and applauded the writer. And, at the March 1901 art exhibition, Tolstoy's portrait by Ilya Repin was showered with flowers. In the same year, Tolstoy was even nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Censorship banned Tolstoy's religious works from being printed. But, like any ban, this only caused a flurry of interest and Tolstoy became an even increasingly cult figure. And the “excommunication”, which was calculated to save believers from Tolstoy's “false teachings”, had exactly the opposite effect.

“The banning of Tolstoy's religious (and not only religious) works from publication in Russia and the persecution of those who distributed them contributed to the popularization of Tolstoy's ideas, which were seen as the truth hidden from the people by the state and the official Church,” Basinsky writes.

Although Tolstoy himself suffered little, the real persecution began against his followers, the ‘Tolstoyans’. The most active ones ended up in exile and prison (especially those who refused to join the army during World War I, because of their religious beliefs).

To this day, Tolstoy has never been “rehabilitated” and wasn't returned to the bosom of the church. As a result, there was no official liturgy at his funeral and only one unknown priest agreed to read a prayer over the grave.

Leo Tolstoy and his sister Maria, who was a nun in Shamardino Convent

Public domainIt is known that at the end of his life, Tolstoy sought closeness to the Church: he came to the monastery of Shamordino, where his sister lived as a nun. He even wanted to go to the Optina Monastery, that he visited more than once before, to carry a strict obedience there. He also sought communication with the Optina elder monks. But, as contemporaries recalled, penance was out of the question. Rather, it became part of his spiritual metamorphosis.

Optina Pustyn monastery

Public domainAlready in the 2000s, several requests were sent to the Russian Orthodox Church to reconsider the 1901 decision of the Synod. But, because Tolstoy didn't publicly repent and didn't recant his convictions, the Church responded negatively each time.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox