Traditional Wayang Purwa theater puppets from Java, carved wooden gods from Vietnam, Japanese samurai swords and those very Chinese shoes, which were put on tightly bandaged little feet… One could almost endlessly add to the list of what awaits visitors at the Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow!

It was established as ‘Ars Asiatica’ in 1918 and was housed in two halls of the Historical Museum on the Red Square. The collection was assembled from items from other museums, gifts from private collectors and diplomatic missions, and was later supplemented by exhibits obtained on expeditions by the museum staff.

For 40 years in row, the permanent exhibition of the State Museum of Oriental Art, consisting of tens of thousands of exhibits, has been located in the 19th-century ‘Lunin House’ urban estate on Nikitsky Boulevard in Moscow. Below are its main masterpieces.

This bronze cup is an ancient Chinese ritual utensil. During the Shang Dynasty, it was used for libations of sacrificial wine. The goblet is shaped like an elegant flower.

A unique ancient Greek silver goblet with gilding was found on the territory of modern Adygea in a sanctuary mound. Today, it is kept in the museum's ‘Special Storage Room’ together with other archeological artifacts.

Another masterpiece from the archaeology section is a small-sized Buddha's head, which was found in the cult Buddhist center of Kara Tepe on the territory of modern Uzbekistan. Behind the curly head we see a fragment of a preserved nimbus. It is assumed that, originally, there was a whole sculpture of Buddha, of which only this part has remained.

In 1948, these Hellenistic ivory wine vessels were found in the ancient settlement of Old Nisa on the territory of modern Turkmenistan. Their lower part (protoma) is made in the form of an animal or fantastic creature. There are four rhytons in the Oriental Museum’s collection. The photo depicts vessels with a winged centaur (left) and with a winged lion-griffin (right).

Among the hundreds of art works from Japan, this wooden statue of a bodhisattva stands out in particular. The meter-high temple sculpture was believed to bring good luck.

This was a gift from Japanese Emperor Meiji for the coronation of Nicholas II in 1896. The 2.3 meter tall sculptural composition is made of wood and ivory. The wingspan of the eagle reaches 164 cm. The whole composition is exhibited against the background of a screen on which Japanese masters embroidered a raging sea.

This black Japanese silk robe embroidered with traditional motifs (flowers and birds) is stunning. ‘Furisode’ literally translates as “long, swaying, flowing sleeve” and, with a length of 183 cm, its sleeves span 140 cm.

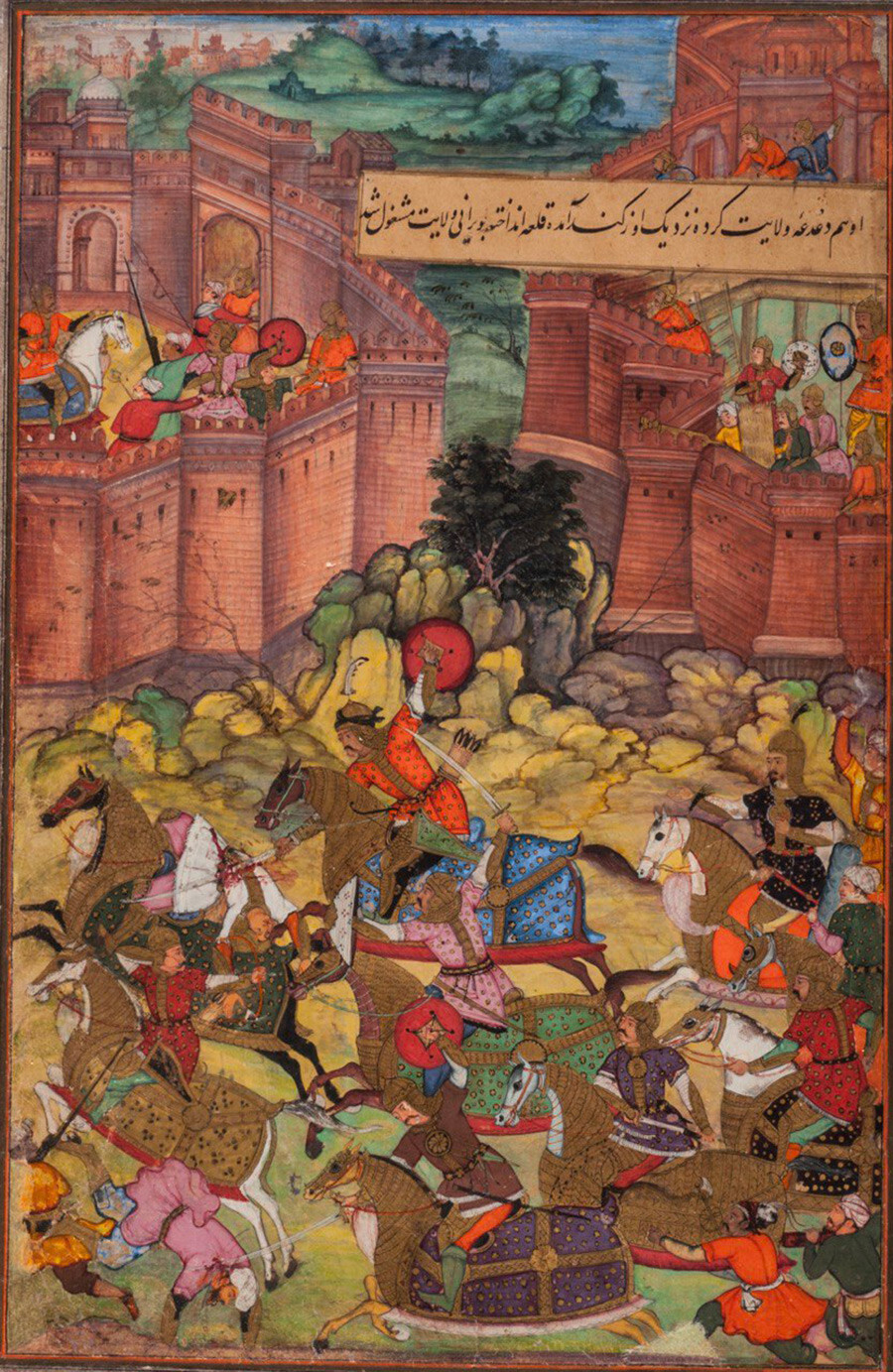

A 57-page manuscript with miniature depictions is an illustrated biography of Shah Babur, founder of the Mughal dynasty. It shows battle scenes, palace life, hunting trips and feasts. This miniature depicts ‘The Battle of Uzgen at the attempt of Abu Bekr Douglat to seize Fergana’. The rarity was acquired by Russian collector Alexei Morozov from Persian merchants at the Nizhny Novgorod fair in 1906.

The jewel of the hall dedicated to Iranian art is this painting of a young girl dancing in the Shah's palace. This is a landmark of the art of the Qajar dynasty. The court painter painted the dancer with special attention to traditional ornamentation and color. In addition, one can endlessly gaze at the details of her costume. Similar paintings adorned the palace itself and were a frequent diplomatic gift.

This is one of the most famous paintings by the Georgian master of primitivism and naive art, Niko Pirosmani. In his distinctive style, he depicted a traditional Georgian feast. And according to eyewitnesses' recollections, he painted from life and quickly, right while the subjects were still having a drink.

The Memorial Cabinet of Nicholas Roerich in the Museum of Oriental Art is decorated with Roerich's portrait painted by his son. The main Himalayan landscape painter and explorer of Tibet and India is depicted in oriental clothes. Four figures can be seen behind him, holding objects representing wisdom: a sword, a casket, a lamp and a book. The retrospective exhibition of the works of Nicholas and Svyatoslav Roerich was the museum's first exhibition in its current building in 1984.

This avant-garde painting was created in Uzbekistan. It combines cubo-futurist art and motifs of traditional oriental painting. You can distinguish the silhouettes of camels and their riders, as well as the rhythm of the dunes. In the Museum, right next to the painting, there is a 3D tactile copy for blind people and, it seems, it will be an aid to those who have not felt the full effect of the canvas.

This portrait of a high-ranking bureaucrat is a striking example of Joseon-era Korean painting. Portrait painting was very common and its characteristic feature was the accurate reproduction of a person's appearance. This is why even the pigment spots on the face are visible in the portrait.

This Joseon-era ceremonial helmet was used not in battle, but in court ceremonies. The hieroglyphs on the medallion under the visor indicate that the armor belonged to a commander. The front part of the helmet's top is adorned with a dragon representing strength and valor.

Traditional Chinese portraits were done after the death of the person depicted, but still with attention to the details of appearance. The author of this portrait is unknown, because it was thought that the portrait genre was the domain of artisans. The inscription says that Chiang Mei The Long Eyebrows bid farewell to the world after 85 years of life. Well, from the portrait, we can see why the patriarch had the nickname “long eyebrows”.

This unique jug combines two eras and two different countries. The base is valuable Chinese porcelain with a cobalt pattern of lotuses and chrysanthemums on a white background. Most likely, the original vessel split, so Iranian masters gave it a second life, making a metal frame. It bears an elegant chased pattern and the curved spout ends with a round rosette with colored inserts.

The Oriental Art museum's collection abounds with ritual attributes of Asian peoples, including masks. This frightening piece is a mask of Maru Raksha, the demon of 18 diseases. The figure of the demon himself is in the center and, on the sides, are images of diseases and mutilations. Such items could be used during ritual actions (in this case, healing) or they could serve as an amulet at home.

It was believed that such a dagger was a sacred object that had magical powers. Its wavy blade refers to the mythical ‘naga’ serpent, the ruler of the underworld. Its head in a crown is forged at the base of the blade.

Such masterpieces of bone-carving art were a kind of entertainment. One could spend hours gazing at the master's filigree work and trying to count how many balls were carved inside the main one. Such openwork Chinese balls became very fashionable in Europe in the late 19th century.

A whole exposition of the Oriental Art museum is devoted to artistic products made of bone by the Chukchi peoples. Engravings on walrus tusks is one of the traditional art forms of the Chukchi and Eskimos. Most often, artists depicted scenes from life and folk legends. This tusk features reindeer sled races, during which Chukchi young men chose brides. The work is made by artist Lidia Teyutinina, a hereditary bone carver and engraver. Her grandfather and father were also carvers, while her mother was the first female engraver in Chukotka.

Russia Beyond is grateful to the Museum of Oriental Art for its help in preparing this material.

To find out opening hours and plan your visit to the museum, visit their website at: orientmuseum.ru.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox