Do you think vampires come from Europe? No, they don’t. It's practically an indigenous Russian phenomenon.

“You (God knows why) call them ‘vampires’, but I can assure you that they have a genuine Russian name, ‘upyr’; and since they are of purely Slavic origin, even though they are met with throughout Europe and even in Asia, there is no basis for holding on to a name deformed by Hungarian monks who took it into their heads to turn everything into Latin and out of ‘upyr’ made ‘vampire’.”

This is a quote from the beginning of the novella ‘The Vampire’ (1841), which, in Russian, is titled exactly ‘Upyr’. The author is Alexei Konstantinovich Tolstoy, a third cousin of Leo Tolstoy, the famous Russian writer and satirist.

In Russian literature, there were already works that featured unclean forces and the dead, a kind of “horror”.

The master of the genre was Nikolai Gogol and his cycles of short stories and novels ‘Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka’ (1831-32), ‘Petersburg Stories’ (1830s) and ‘Mirgorod’ (1835), in which ‘Viy’, one of the most terrifying works of Russian literature, especially stands out.

All of Gogol's fantastic works are divided into two types:

– Either they are stories with humor, where the unclean force is not scary and organically lives next door to people. In ‘The Night Before Christmas’, a blacksmith saddles the devil and makes him help himself.

A still from 'The Night Before Christmas' movie

Alexander Rou/Gorky Film Studio, 1961– Or, on the contrary, there are very scary, pseudo-realistic stories, where the dead rise from their graves and scare ordinary people at night.

A. K. Tolstoy's tale stands somewhat apart.

The novella ‘The Vampire’ begins with a scene in a crowded ball. A young, but already completely gray-haired man named Rybarenko tells the protagonist, Runevsky, that the ball is full of vampires. And lists who exactly is among them. Rybarenko claims that he himself attended funerals of many of them and, now, they are here, ready to drink the blood of young people.

Runevsky is confused and, at first, refuses to believe it, considering the interlocutor to be crazy.

A still from 'Drinking blood'

Evgeny Tatarsky/Lenfilm, 1991The character falls in love with a young lady named Dasha, whose grandmother is also rumored to be a vampire. And even Dasha's mother allegedly died very young… and her blood was found on her grandmother's dress…

Over time, according to some details and circumstantial signs, Runevsky begins to believe in vampires. And then, it begins to seem to him that his beloved Dasha is also not of this world.

Immersed in his thoughts and doubts, Runevsky meets his interlocutor, Rudenko, who asks not to think of him as crazy.

“Yes, kind friend, I, too, am young, but my hair is gray, my eyes are sunken, I have become an old man in the bloom of years – I have lifted the edge of the veil, I have looked into a mysterious world.”

Rybarenko tells a mysterious story. Once, being in Italy, he and his friends snuck into an abandoned gothic mansion, which everyone in the neighborhood called a “damned house”. At night, mystical things happened. And none of them could understand what was delirium and dream and what was reality or even maybe someone's malicious prank?

It turned out that, long ago, there had been a pagan temple in that place, where lamias, or empuses, who were very similar to Russian ghouls, practiced their trade.

A still from 'Upiór', the Polish film adaptation

Stanislav Lenartovich/Kadr creative group, 1967In Moscow, Runevsky meets Vladimir, the brother of his beloved Dasha, who happened to be with Rybarenko in that house in Italy. And Vladimir tells a completely different story about that time (that someone added opium into their wine glasses).

In the finale, the reader is left with a choice: who to believe? Crazy Rybarenko, who blindly believes in vampires? Or Runevsky, who doubts, but thinks that there is some mysticism? Or Vladimir, who explains everything logically, without a shadow of mysticism.

‘The Vampire’ by Tolstoy was twice adapted for the screen. In1967, a Polish movie with the same name was released and, in 1991, the thriller ‘Drinking Blood’ was released in the USSR.

It is believed that Tolstoy wrote ‘The Vampire’ (1841) under the influence of ‘The Vampire’ (1819), a novel by English writer John William Polidori. In it, for the first time, the wild bloodsucking monster is presented as an aristocrat.

Bram Stoker's ‘Dracula’ came out much later, in 1897. It was Lord Byron himself who prompted the plot of ‘The Vampire’ to Polidori. However, the similarity of the story to Tolstoy is limited to the outline of the plot.

A still from 'Vourdalak', based on Tolstoy's 'The Family of the Vourdalak'

Sergei Ginzburg/Gorad, 2017Even earlier, Tolstoy wrote a gothic story titled ‘The Family of the Vourdalak’ (1839), securing in the Russian language Pushkin's neologism ‘vourdalak’ as a synonym for ‘vampire’. But, the story was published only in the 1880s, after the author's death.

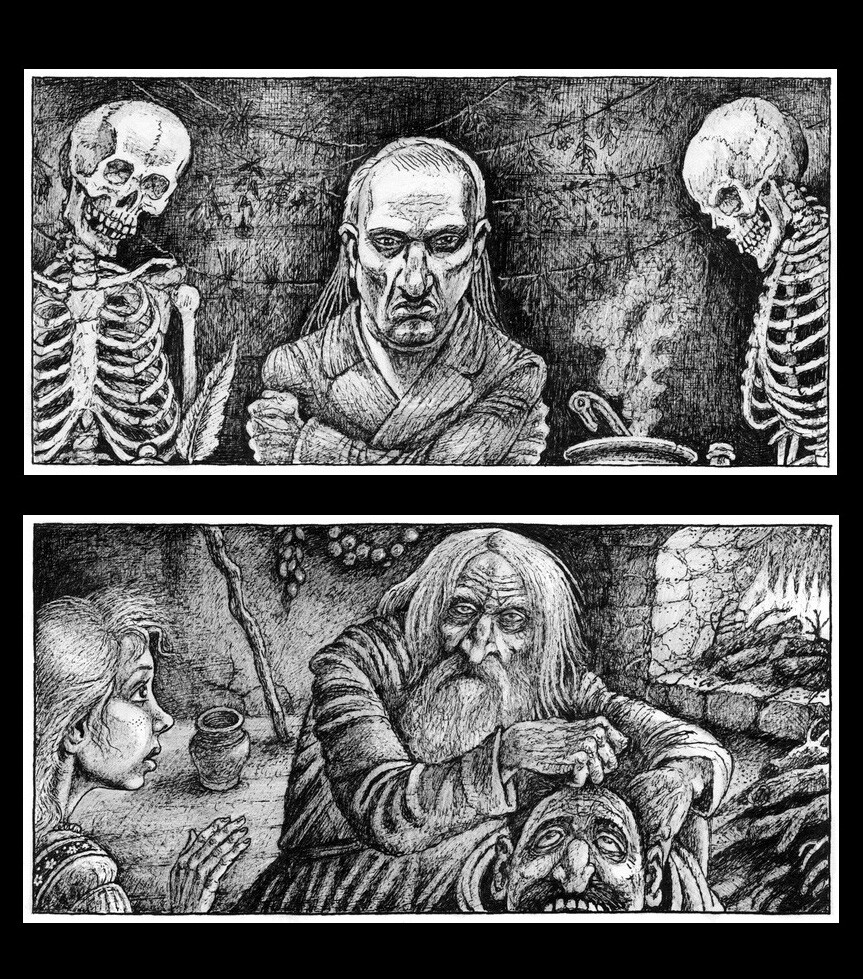

‘Upyr’ is a primordial Russian word. There were such characters in Slavic mythology: the dead, rising from their graves and sucking the blood of the living. Some ‘Upyrs’ were heroes of Russian folk tales, as well. But, most often, they were people excommunicated from the church and one could be protected from them only by splashing holy water on them.

Upyr, a character of Russian folk tales

Ivan Ivanov/Fenix, 2020‘Upyrs’, in general, resemble Western European vampires and linguists believe that the words ‘upyr’ and ‘vampire’ have a common origin. For example, their word relatives, ‘vupyr’ in Belarusian and ‘vapir’ in Bulgarian, are very similar. In Turkic mythology, there is also a bloodthirsty creature called an ‘ubyr’, whose name comes from the word ‘suck’, ‘absorb’.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox