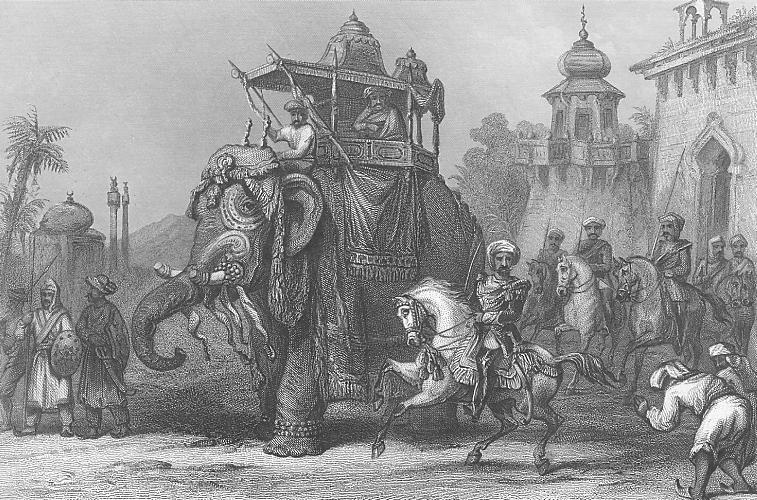

Maharaja Duleep Singh (1838-1893), Maharajah of the Punjab. Engraved by D.J. Pound (ca. 1860s)

At the end of the 19th century there were persistent rumours in India that legendary Maratha aristocrat and fighter Nana Sahib was still alive. The worst enemy of the British Raj in India disappeared after the fall of Kanpur. All the other leaders of the 1857 Indian War of Independence were either killed in battles or hanged by the British. Only the fate of Nana Sahib was unclear. He was “seen” in different parts of India, but many people believed that he left the country and went to Russia to seek the help from the Russian Tsar.

Actually there is no any evidence that Nana Sahib ever visited Russia. Most likely, these rumours were spread by his supporters who didn’t want to believe that their leader died in 1857. But there is no fire without smoke. Several members of Indian aristocratic families really did live in Russia during the 19th century. Some of them were just adventurers who wanted to gain fame and popularity. It was not very difficult, because the sight of an “Indian prince” was extremely interesting for the Russian public.

Nana Sahib with his escort. Steel engraved print of 1860

Nana Sahib with his escort. Steel engraved print of 1860

Some Indians dreamt of independence from the British Empire and wanted to get support from the Russian government. But the biography of any of them can be used as a plot for an adventure film.

A young man claimed to be a descendant of the kings of Bijapur. It is almost impossible to understand if he was an impostor. One can only discern that he was an Indian, who was educated in France and converted to Christianity. He was given the name Alexander and the surname Porus in honour of an ancient Indian king, who fought against Alexander of Macedonia. The ‘Prince of Bijapur’ came to Russia in the late 1770s. He had a career in the Russian Army. During the reign of Paul I he became a colonel of a Hussar regiment. Prince Porus of Bijapur was well known in St. Petersburg due to his passion for various incredible projects. The ‘Indian prince’ gets mention in several Russian literary works. He is mentioned in the famous comedy ‘Woe from Wit’ by Alexander Griboyedov. The ‘prince’ married a Russian woman and we can trace the history of his family till the middle of the 19th century.

Ramchandra Balaji claimed that he was a nephew of Nana Sahib. With a high degree of probability, he really comes from a noble Maratha family and was brought to Europe after the War of 1857. Ramchandra Balaji joined the Russian Army during the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878. After the end of the war he came to St. Petersburg.

The name of Nana Sahib was well known among the Russian public of that time, and his ‘nephew’ soon got acquainted with famous Russian geographer Pyotr Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky, who recommended Ramchandra for a scientific expedition to Central Asia.

The main purpose of the expedition was to explore the nature and geography of Turkestan, which had become a part of Russia only several years earlier. Ramchandra, who was a well-educated person, took part in all the scientific activities, but he also had his own goals – to establish contacts with Indian diaspora in the region and to return to his homeland via Afghanistan.

Ramchandra was in the middle of the ‘Great Game’ between Russia and Britain. Unfortunately, both sides considered him to be the agent of their enemy. In 1881 Ramchandra Balaji had to leave Russia by the order of the authorities. Further details of his life remain unclear.

The royal status of Maharaja Duleep Singh cannot be questioned. He was the youngest son of Ranjeet Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire.

After the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-1849), Punjab was annexed by the East India Company. Duleep Singh, who was 11 years old in 1849, became a “honourable prisoner.” In 1854 he was sent to exile to Britain. The British government wanted the young man to be a loyal subject of the empire. He was given a solid stipend and Queen Victoria was the godmother of his children.

However, by the beginning of the 1880s the relationship between Duleep Singh and the British authorities had soured. Duleep wanted to visit India, but the colonial administration was afraid of the reaction of the Sikh community. Some Sikhs still considered Duleep as their legitimate ruler.

Duleep also wanted the British administration to return his family estate in Punjab but the authorities refused.

Duleep Singh then decided to break off all his connections with Britain and establish contacts with Russia. At that time, the Britain-Russia relationship was extremely cold, as the ‘Great Game’ in Central Asia was at its peak. The deposed Sikh Maharaja hoped that Tsar Alexander III would help him re-establish a monarchy in Punjab.

The Russian government in St. Petersburg was rather sceptical of Duleep Singh’s proposals to start a rebellion in Punjab. But he managed to get in touch with Mikhail Katkov, the editor of influential Russian newspaper ‘Moscow News.’

Russian Indologist Alexey Raikov wrote in his book ‘Rebel Maharaja’ (2004) that Katkov invited Duleep Singh to Russia. The erstwhile ruler of the Sikh Empire came to Moscow in 1887 with his family.

The arrival of an Indian prince attracted a lot of attention in Moscow. Duleep gave dozens of interviews to the Russian press and proclaimed himself as the “ruler of Punjab.”

However his real influence wasn’t so great. Duleep Singh’s supporters in Punjab were arrested by the colonial authorities, and the Russian government did not want to start a conflict with the British Empire.

Duleep Singh nearly spent two years in Moscow, but finally decided to re-establish ties with London.

Given the fact that the borders between India, Afghanistan and Central Asia were porous, it is very likely that there were a larger number of Indians who actually made it all the way to Russia. A greater amount of research could help uncover fascinating and hitherto unknown links.

(The information about Ramchandra Balaji’s stay in Russia was sourced from a collection of documents titled ‘Russian-Indian Relationships in the 19th century,’ Moscow 1997).

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox