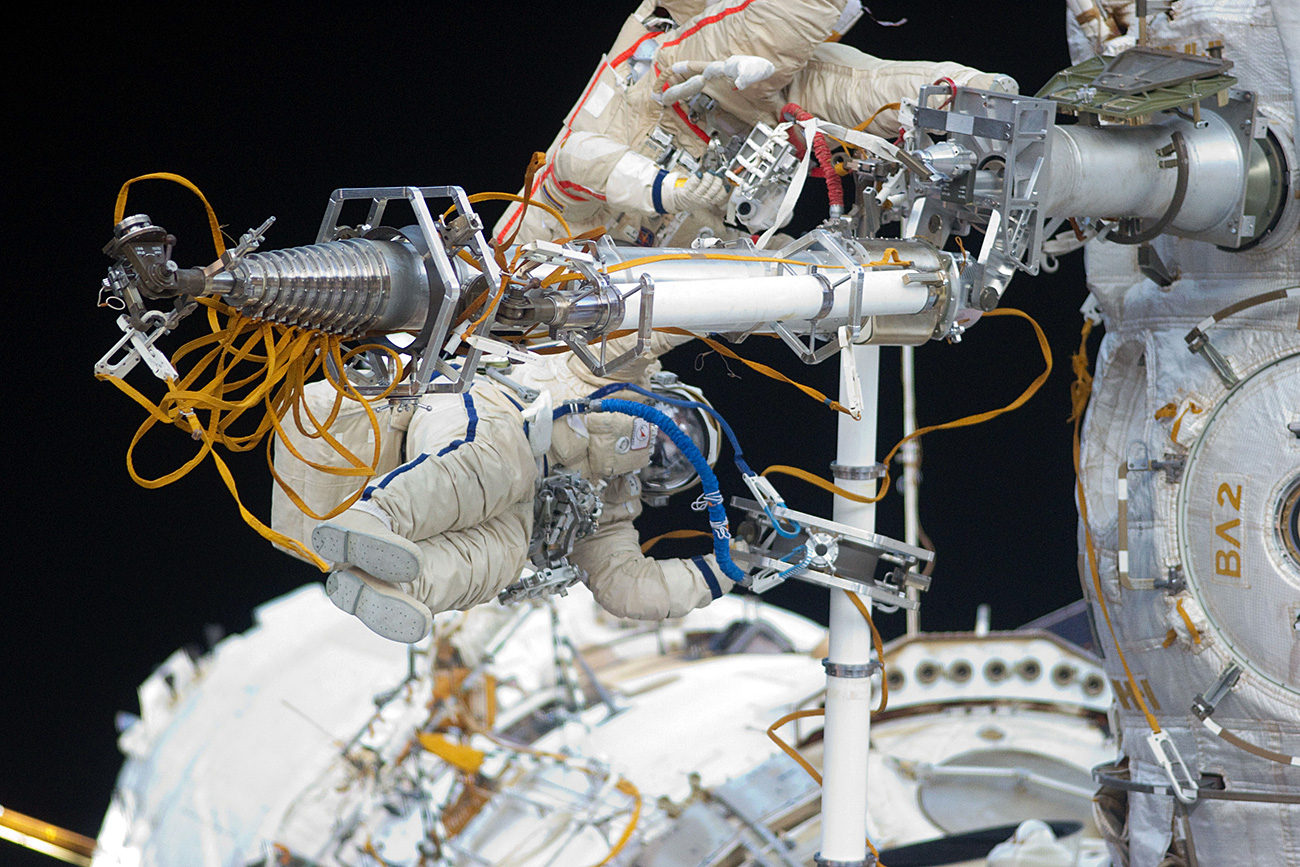

Member of the main crew of ISS-52/53 Mission to the ISS Sergei Ryazansky.

Eugene Odinokov/RIA NovostiCan you imagine a biologist who is also the commander of a spaceship? And how is it possible – to be a cosmonaut and at the same time to have never been to outer space? There was a time when this would have been a big deal but now, it isn’t.

This contradiction is personified by the cosmonaut Sergey Ryazansky, who set the record for the longest Russian spacewalk (8 hours and 5 minutes) and took the first Olympic torch into space. But until these opportunities arose, Ryazansky had never even dreamed about such things.

His next expedition to the International Space Station (ISS) will be in July 2017. Ryazansky was selected as the commander of a space crew, which also includes Italian Paolo Nespoli and American Randy Bresnik.

European Space Agency astronaut Paolo Nespoli, Roscosmos cosmonaut Sergei Ryazansky and NASA astronaut Randy Bresnik after the comprehensive training using the 'Teleoperator' simulator at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center. / Eugene Odinokov/RIA Novosti

European Space Agency astronaut Paolo Nespoli, Roscosmos cosmonaut Sergei Ryazansky and NASA astronaut Randy Bresnik after the comprehensive training using the 'Teleoperator' simulator at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center. / Eugene Odinokov/RIA Novosti

“The rocket launch at night is insanely beautiful. Especially when you look at it from the cosmodrome. But when you are inside the shuttle, first of all, you can’t see anything. Second, you start to suspect that something is wrong here: that in fact, you are sitting on a huge barrel of gunpowder. Eventually, right on time, there is a “boom” and then, just 528 seconds after takeoff, you are in orbit.

The ISS is a long iron tube, 60 meters in length with six cabins. Nevertheless, at one point we had nine crew members. Well… someone lived in the laboratory, someone in the storeroom and someone on the ceiling. By the way, even in an absolutely round module, we have a designated floor and ceiling. It is really important for your health to keep things oriented like the Earth in your mind.

Baikonur Cosmodrome. / Global Look Press

Baikonur Cosmodrome. / Global Look Press

One orbit around the Earth from the ISS takes 90 minutes, which makes the day 45 minutes long and the night 45 minutes long. The difference to us is between a day off and a working day. People from Earth cannot contact you first, but when you wake up the task list is awaiting you, as usual.

Every day, a cosmonaut has two hours of sports activities. And, please, nobody eats from tubes. We have a lot of freeze-dried food as well as canned goods.”

“One time the ISS lost 70 percent of all electricity and, as a result, 70 percent of all computers. There was an emergency situation in the American segment. We were calling to the Mission Control Center and saying something like ‘Houston, we have a problem.’ ‘Houston’ said: ‘Accepted. Just go to sleep.’ So, that was a really stressful situation. The worst case scenario, of course, was that we would have to return home (the chance was around 60 percent). But while we were sleeping, NASA brought together astronauts, everyone who had been working on this project—from all over the world— by plane, and got them to practice working through the situation (a space simulation). To be honest, I didn’t think it was possible. But the next day we had instructions on what we had to do.

By the way, the worst thing about space is not the troubles there. It is when there is something that you have forgotten to do on Earth.”

Russian cosmonauts. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

Russian cosmonauts. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

“For example, a cosmonaut has to be able to jump out of a plane with a parachute and solve a task before the parachute opens. There is also the stress resistance test. I was surprised but, on the average, I do that twice as fast as on Earth (12 sec against 24 sec).

Another test is that you are locked in a tiny room without sleep for three days and are forced to be constantly doing something–writing, talking, completely focusing on a task. If you are forced to carry out an emergency landing, you will need to be able to react quickly because one missed second in such a situation equals an 80-200 kilometer detour from your destination on Earth.”

An astronaut aboard the ISS enjoys a weightless snack. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

An astronaut aboard the ISS enjoys a weightless snack. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

“I had dreamed of being a biologist since I was a child. And after graduating as a biochemist, I began working at the Institute of Biomedical Problems. At some point, the Russian Academy of Sciences announced openings for scientists to conduct space experiments. For some reason, we seemed to have scientists who were either very smart or very healthy. I’m the second type, so only I was selected as a research-test cosmonaut.

By 2005, my training was complete. Two years before that, NASA’s space shuttle Columbia had disintegrated in the Earth’s atmosphere and killed everyone in the seven-member team. And so the problem was that NASA had bought out all the scientific sites until 2017. And no one wants to pay a man who will not go anywhere for the next 12 years. ‘Nothing personal, it’s just business,’ I said to myself. And it was only at that moment that my desire to go to space really appeared.

Stargazing from the International Space Station. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

Stargazing from the International Space Station. / ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

I did not go to space, but I participated in the 105-day mission of the Mars 500 program–a simulation of an Earth-Mars shuttle spacecraft. During the press conference after the mission, the Military General and head of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, asked when I was going to go to space and my answer was ‘Never.’ ‘But aren’t you a cosmonaut?’ he asked. ‘Yes’ ‘So when are you going to go to space?’ he repeated. ‘Never.’ I said again. He could not understand all the restrictions regarding the spacecraft that launches the cosmonauts into space, and he decided to make me an exception. They allowed me to become the first flight engineer without a formal engineering education.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox