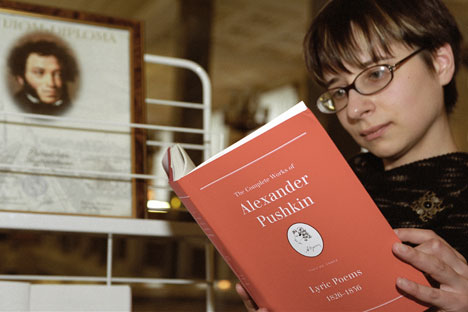

Which Russian books besides classics does the English world know?

Alexander Polyakov / RIA NovostiWhen English-speaking readers talk about Russian novels, they generally mean Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, Bulgakov and Pasternak. How many of us read works by 21st-century Russian writers? And, if not, what kinds of books are we missing? There is no shortage of serious literary fiction coming out of Russia, but the best-selling contemporary authors write, as they do in many languages, horror stories, fantasy and whodunits.

In Sergei Lukyanenko’s Night Watch series, supernatural beings do battle on Moscow’s streets. Andrew Bromfield translated the first book into English in 2006 and it sold millions worldwide, winning an international following. A sixth book, already extensively pre-ordered, is due out next summer. Bromfield also translated Boris Akunin’s successful cascade of effortlessly elegant whodunits, featuring diplomat-turned-detective Erast Fandorin. Part I, set in 19th-century Moscow, London and Petersburg, was published in English as The Winter Queen in 2003. Agnes Kindrachuk from Montreal recommends Akunin for “fun reading”.

Dmitry Glukhovsky found an international audience with his Metro 2033, a post-apocalyptic underground adventure set in the disused tunnels of the Moscow metro. Published in English in 2011, it became a European cult bestseller, shifting nearly two million copies of the printed edition worldwide, with equally large numbers downloading the Russian digital edition. Ksenia Papazova of Glagoslav, a publishing house specializing in translated Russian books, told RBTH that their Dutch translations of Glukhovsky’s fantasy and its sequel Metro 2034 were consistently among their top bestsellers: “He is very famous in Russia, and Dutch science-fiction fans find it very interesting as well.” Metro 2035 came out this year in Russian and will be translated soon.

Glagoslav’s current bestseller is far more surprising: Maria Rybakova’s Gnedich (2015) is a novel-in-verse about a 19th-century poet, Nikolai Gnedich, who translated Homer’s Iliad. Papazova believes that interest in contemporary Russian authors is generated by “the reputation of Russian classics”, but knows there is little chance of attracting “the same number of readers as J.K. Rowling did.” Numbers of readers globally are shrinking, she explains, and most Russian fiction is “serious … not meant to entertain but to make the reader think and question themselves, and search for answers.” Papazova sees an important role for publishers in helping this discerning readership discover contemporary masterpieces: “Tolstoy and Dostoevsky do not need any marketing,” she says, “but new authors do!”

Allesandro Gallenzi of Alma Books also sees a contrast between the easy sales of famous names from the past and the challenge of introducing the unknown modern authors. He told RBTH: “Our Russian classics program is by far the most successful strand in our list. I believe there is a great appetite for Russian culture and literature among English readers – but the trouble, in my view, is that a lot of Russian contemporary novels are too self-referential and Russo-centric. This makes them difficult to export into other languages.”

'Read Russia' at America Book Expo in 2003. Source: Read Russia / press photo

'Read Russia' at America Book Expo in 2003. Source: Read Russia / press photo

“We have published, successfully, many Russian titles, mostly from the 19th but also from the 20th century (Bulgakov, Bunin, Dovlatov),” Gallenzi explains. The only contemporary Russian books Alma has published so far are Dmitry Bykov's Living Souls and Alexander Terekhov's The Rat Catcher. “They both sold reasonably well,” Gallenzi says, but sales were still a fraction of those generated by earlier classics. Terekhov’s gruesome tale of two Muscovite rat catchers exterminating a provincial plague sold better than Bykov’s grimly comic cycle of imaginary Russian civil wars. Gallenzi surmises: “I think The Rat Catcher was more accessible, and its sharp satire more appealing than Bykov's dystopian novel, which required a certain knowledge of Russian history and culture.”

Vladimir Sorokin and Victor Pelevin have also written violent, literary dystopias with some appeal for international readers. Day of the Oprichnik (FSG, 2012) was well reviewed, but Amazon reviews suggest general readers sometimes struggled; Seamus Sweeney from Dublin found “the excess of this dystopian vision rapidly becomes repetitive,” while J. Kevin White, a US-based Pelevin fan, describes it Sorokin’s novella as a book with “almost no redeeming features”. Pelevin’s fiction, especially his late-20th-century classic Omon Ra, is more perennially popular.

Some of the best-loved “Russian” authors actually write in other languages, like Francophone Andreï Makine, whose novels are often set in his native Russia. British reader Henrietta Challinor comments: “For me, Makine writes with the melancholic soul … of the best Russian writers, but his language is rich with a lightness of touch more akin to the great French writers.”

Gary Shteyngart, Keith Gessen and Boris Fishman, all writing in English, join a celebrated tradition of Russian-American fiction dating back at least to Vladimir Nabokov. Their texts are peppered with Russian literary allusions, like Fishman’s antihero in A Replacement Life, Slava Gelman, whose nickname “Gogol” reinforces the novel’s echoes of Dead Souls. Andrey Kurkov had an international hit with his novel Death and the Penguin when it appeared in George Bird’s 2001 translation. Kurkov, who has published prolifically ever since, is a Ukranian author writing in Russian.

The dynamic, expanding Pushkin Press, which – despite the name – only started publishing Russian books relatively recently, has had successes with a couple of Soviet classics. Contemporary writers are represented so far by one adult novel and one children’s book (Mikhail Elizarov’s The Librarian and Anna Starobinets’ Catlantis respectively), but there are plans for more. Gesche Ipsen of Pushkin Press told RBTH, “Try us again in a couple of years; hopefully we’ll have more on board then.”

Papazova sees a chance today to redress Russia’s Soviet-era isolation by promoting authors abroad: “Nowadays we have an opportunity at last to fulfill this mission and to translate the books into English. Thus, the global readership has a chance to re-discover contemporary Russian literature.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox