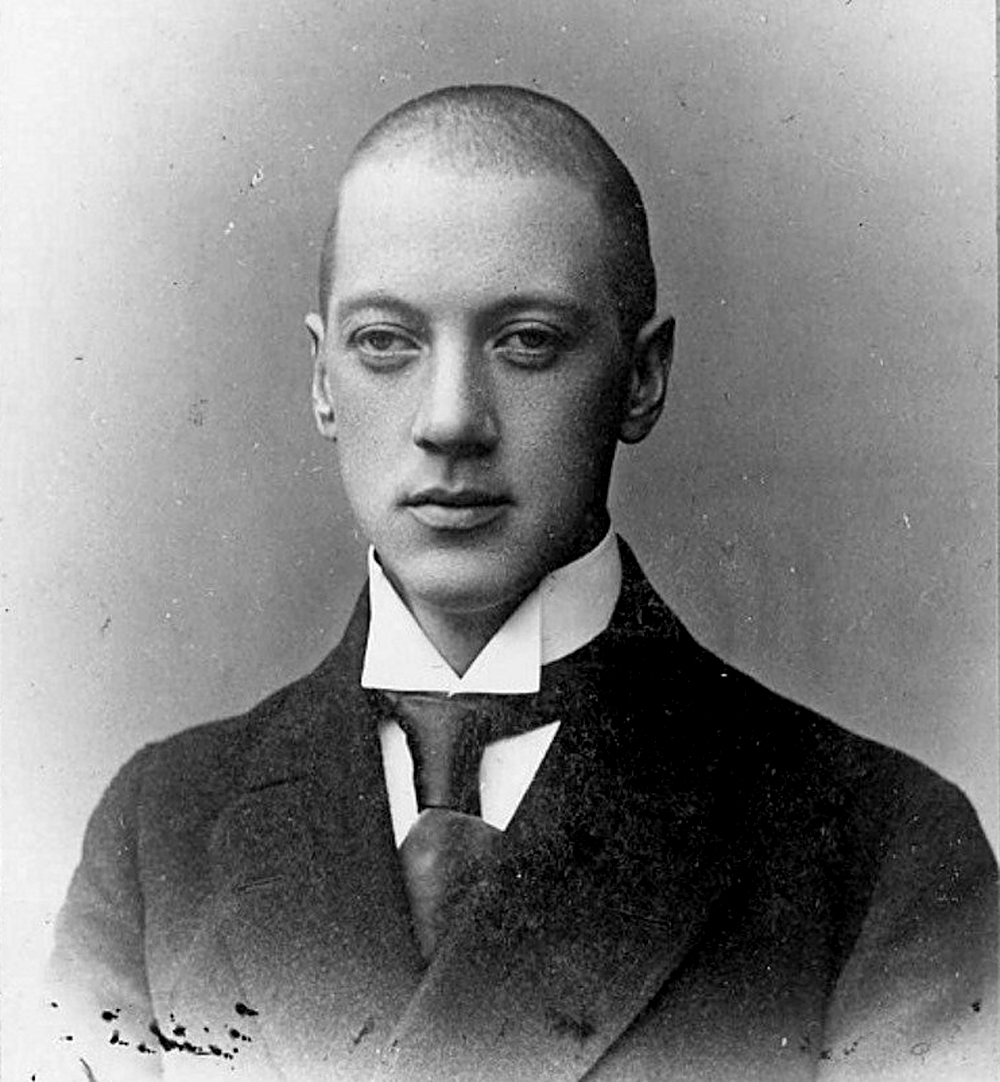

Nikolay Gumilyov

Karl BullaNikolai Gumilev had many guises in his life: romantic, leading light of Russian Silver Age poetry, officer, intrepid traveler, explorer and womanizer. He went from being a war hero in his younger years to an enemy of the state, falling foul of the Soviet authorities in the prime of life.

Gumilev was born in Kronstadt near St. Petersburg. Living next to the sea filled him with wanderlust from an early age, and he travelled extensively around Europe, before making several expeditions to Africa, where he visited Egypt, Somalia, Ethiopia and Djibouti. These trips were very dangerous, with the threat from wild animals and aggressive tribes compounded by food and water shortages. The party of Petersburg intellectuals even had to hunt for food at one point. In 1914, however, an expedition led by Gumilev brought a large collection of local works of art and items back to the Tsarist capital. Africa inspired Gumilev to write several poems and songs, including “The Galla”, “The Giraffe” and “The Sahara”, quoted below:

All deserts are one tribe, from the beginning

of time, but Arabia, Syria, Gobi —

they’re only ripples of the vast Sahara

wave that roared its satanic spite.

The Red Sea heaves, and the Persian Gulf,

and Pamir stands thick with snow,

but Sahara's sand-floods

run straight to green Siberia.

(Translated by Burton Raffel and Alla Burago)

Several literary movements emerged in Russia in the early 20th century, and in 1912 Gumilev declared the foundation of Acmeism – a reaction to Symbolism’s extreme and abstract elements. Acmeism centered around direct expression through images and the accuracy of the word. The movement was joined by major Silver Age poets, including Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam and Sergey Gorodetsky, and it grew to encompass painting and music as well as literature.

Gumilev was without doubt a ladies’ man, and his love affairs included an actress, poet, dancer and even a revolutionary. He had a checkered love life that included a duel, several suicide attempts, three children and two marriages.

His first wife was the famous Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, who he met as a young man. They had a passionate romantic and literary life, dedicating numerous lyric poems to each other. The marriage lasted eight stormy years before finally breaking down. The pair had already split up by the time Gumilev was declared an enemy of the people, but Akhmatova did not denounce him and helped preserve his poetic legacy.

Their son, Lev Gumilev, went on to achieve multi-disciplinary success as a scientist, ethnographer, historian and writer.

Gumilev greatly enriched Russian literature by his incredibly varied translation work. As well as European poets such as Shakespeare, Baudelaire and Southey, he translated Chinese poetry, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and Abyssinian folk songs that he encountered while travelling in Africa.

When the First World War broke out, Gumilev volunteered immediately. He proved himself to be a brave soldier with a keen desire for glory and was decorated twice with the Cross of St. George, ultimately becoming an officer.

Although many renowned poets from that era composed poems with a patriotic or military theme, only two volunteered to fight: Gumilev and Benedikt Livshits.

Gumilev was against the Bolshevik Revolution but refused to emigrate. He made no secret of his views, openly crossing himself in front of churches and announcing his tsarist sympathies. As he was an influential literary figure, he soon came to the attention of the authorities, and was arrested on suspicion of involvement in an anti-Soviet conspiracy. He was executed at the age of just 35. We still do not know precisely when or where this took place, or where the poet was buried. Researchers also disagree whether Gumilev participated in the conspiracy, or if the case against him was completely fabricated.

Gumilev was the only great Silver Age poet to be executed. The others were either exiled, imprisoned, driven to suicide, or died from mental and physical distress before their sentence could be carried out.

Gumilev’s poem The Lost Tram seems to predict that he would suffer this fate:

The executioner, with a face like an udder,

red-shirted, stout as an ox,

has chopped off my head. Along with the others,

it lies at the bottom of a slippery box.

(Translated by Boris Drayluk)

Nikolai Gumilev’s poetry was banned for more than 60 years after his death, and it was only during perestroika that his case was reviewed. He received a posthumous acquittal for the charges of counter-revolutionary conspiracy, and his poetry was restored to the official canon of Russian literature – far later than that of Tsvetaeva and Mandelstam.

Go to www.gumilev.ru for English translations of Gumilev’s poems.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox