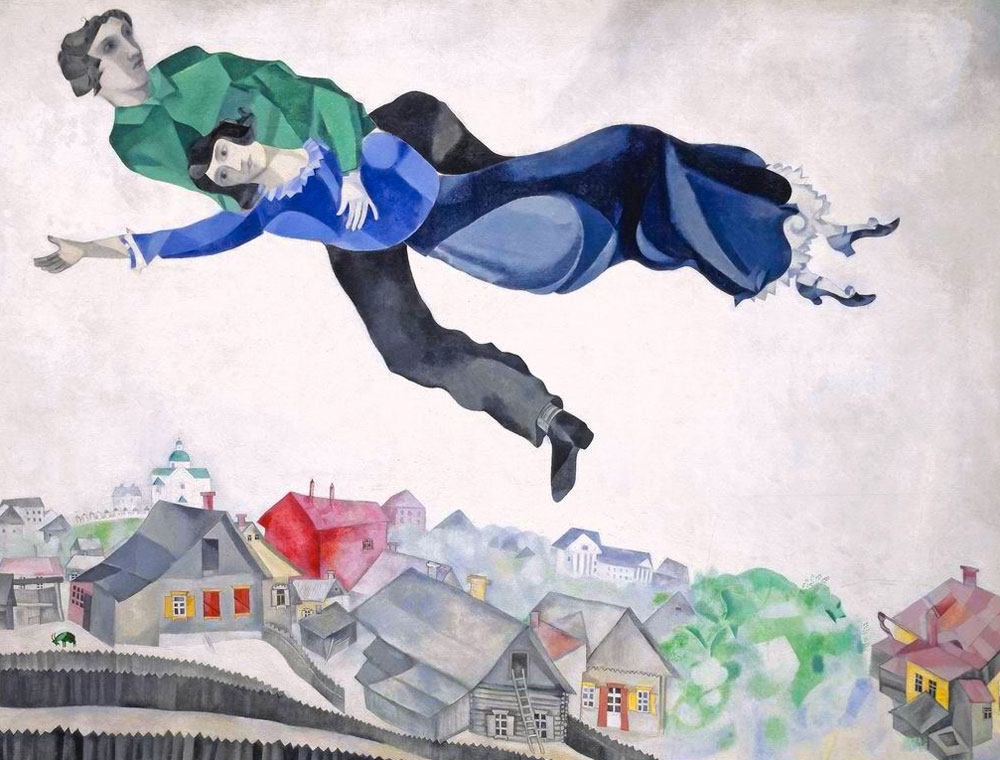

Marc Chagall’s bittersweet impressions of Russian life

Over the town

State Tretyakov GalleryMarc Chagall was born on July 6, 1887 in Vitebsk (now in Belarus) into a poor and traditional Jewish family. During his childhood and youth, anti-Semitism and pogroms were common in the Russian Empire. In My Life, which was written in the early 1920s, the artist provides a lighthearted look at his life in Russia.

Chagall shared many pleasant memories and there are interesting historical anecdotes from his childhood, including the time Tsar Nicholas II visited Vitebsk to review regiments that were about to go to the Far East to fight in the Russo-Japanese war.

“Hosts of boys, excited and sleepy, were met along the way, and headed in long lines towards fields covered with snow,” he wrote.

After waiting for hours in ankle-deep snow, the boys saw the train carrying the entourage. From a distance he saw the tsar who wore a private’s uniform and looked “very pale.”

At age 19 Chagall moved to St. Petersburg, where he was a student of renowned Russian painter and theater designer Leon Bakst. He struggled materially during his student days and could only afford to rent half a room. He described an incident when he witnessed a drunken roommate forcing his wife to have sex with him at knifepoint.“I realized then that in Russia, Jews are not the only ones who have no right to live, but also many Russians, crowded together like lice in one’s hair,” he wrote.

The artist was relieved to experience more freedoms when he moved to Paris in 1910. Although he was happy in the French capital, Chagall craved to be back in Russia. But his love for the works of European artists kept him in France. After a visit to the Louvre, which had the works of Manet, Delacroix and Courbet, Chagall “wanted nothing more.”

“Here in the Louvre… I understood why I could not ally myself with Russia and Russian art,” he wrote. “Why my very speech is foreign to them.”

Back to Russia

In the autobiography, Chagall describes meeting his future wife Bella Rosenfeld.

“Her silence is mine, her eyes mine,” he wrote. “It is as if she knows everything about my childhood, my present, my future, as if she can see right through me.”

My life, 1994. Source: amazon.com My life, 1994. Source: amazon.com |

In 1914, he visited Vitebsk to marry Bella. What he expected to be a short visit turned out to be an eight-year stay as the outbreak of the World War I forced Chagall to remain in Russia.

Over the next few years, the artist became famous throughout the country and his works were displayed in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, he became the Commissar of Arts for Vitebsk and founded the Vitebsk Art College. Chagall later moved to Moscow with his wife, but experienced little professional success. Facing poverty and a difficult life in the Soviet Union, he applied for an exit visa in 1921. He began penning his memoirs as he was waiting to move back to France.

Despite the harshness of Russian life and the discrimination that Chagall faced, from his autobiography it was obvious that he harbored little ill will towards Russia. His greater attachment, of course, was to his hometown Vitebsk, but nonetheless on the page there is a clear yearning for acceptance by his native country.

Marc and Bella Chagall, August 1934, Paris. Source: Getty Images

Marc and Bella Chagall, August 1934, Paris. Source: Getty Images

The book concludes with his final thoughts as he was about to leave for Paris: “And perhaps Europe will love me, and with her my Russia.”

Nine decades later, Marc Chagall is fondly remembered in Europe as one of the great artists of the 20th century and Russia has reclaimed him as one of her own sons.

IN PICTURES: 10 most expensive paintings by Russian artists

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox