How literature was used to 'temper' Soviet people

A screenshot from "How the Steel Was Tempered" movie, 1975. Vasily Konkin (L) as a main character, Pavka Korchagin.

kinopoisk.ruNikolai Ostrovsky, who wrote the cult novel How the Steel Was Tempered and died at 32, overcame much in his short life. He survived a difficult childhood, adolescent involvement in underground political groups, combat military service, work as a party functionary and a serious illness at 25 that left him writer bedridden and gradually blinded him. In another era, this biography could have served as a wonderful foundation for a romantic myth. But in Russia in the early 20th century, it became something much bigger. Instead of a story of an individual whose willpower and talent overcame the painful blows of fate, Ostrovsky’s life story was remade by the Soviets into a tale about how a "new man" could be forged from heterogeneous and often worthless "human material." This new man was a participant and co-creator of the new socialist society.

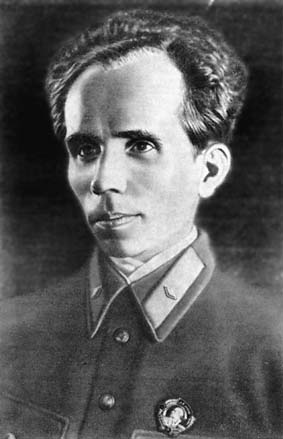

Nikolai Ostrovsky. Source: Archive photo Nikolai Ostrovsky. Source: Archive photo |

Ostrovsky was not the only writer who helped build the socialist future. In the beginning, radical Russian avant-garde artists Velimir Khlebnikov, Marc Chagall, Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky were ardent supporters of the Communist Revolution. Not without reason, they saw in the Bolsheviks the same leftist ideals they embraced.

"To accept or not to accept? For me (and other Moscow futurists) this question did not exist. My revolution. I went to the Smolny. I worked. I did everything I had to," wrote Vladimir Mayakovsky wrote in his 1928 autobiography.

Soviet literature from the Stalinist period is full of stories in which people are likened to pieces of iron out of which Communism, like a hammer, forges new people. The theme is evident even in the titles of works from the period. Alexander Serafimovich's The Iron Flood (1924) is a novel about the Tamask Army's campaign in the summer of 1918 during the Russian Civil War, in which the disconnected and demoralized soldiers transform into a united super-being; Ostrovsky's How the Steel Was Tempered (1932) is a story of a talented yet undisciplined youth who turns into an impeccable "party soldier" — a typical Soviet existence; Mikhail Sholokhov's Virgin Soil Upturned (1932, 1959) uses the same metaphor of something wild turning into something civilized, but in a village rather than on the battlefield; Boris Polevoy's Story of a Real Man (1946), based on a true story, tells the tale of a pilot who despite his broken legs crawls for many days (in the winter, in the snow) to the front lines and is able to return to combat despite having both legs amputated below the knees.

Polevoy’s hero buckles his prostheses to the pedals of his airplane with special spring-loaded clamps that help him feel their movement — the man has literally turned into a machine. Obviously, Polevoy didn't intend this to be the message of the book. He sincerely admired the pilot's courage, but the matrix of socialist realism dominant in art at the time led him to present the story that way. The same transformation can be seen in Maxim Gorky’s novel Mother (1906) in which descriptions of the most intimate human relations, relations between a mother and son, are substituted by descriptions of how a simple "ignorant" woman turns into a "new person," a fighter and a revolutionary.

Alexei Tolstoy was not so naïve when he consciously reworked The Adventures of Pinocchio into his novel Golden Key (1936). Mindful of the times, Tolstoy transformed this moralistic tale into an allegory bubbling with wit. In the modern work, the fairytale protagonists are transformed into bohemians from pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg and expatriate Berlin. And in the character of Pinocchio himself, the wooden boy who, thanks to his innate courage, fast reflexes and incredible purposefulness becomes the leader of his community and the star of the puppet theater, readers recognize a new person who crawls on unbending legs towards a radiant future.

After the Khrushchev "thaw" in the 1950s, the immaculate protagonists of Soviet literature also, in a literal sense, melted. They acquired contradictions and reflexes. But the protagonists of Nikolai Ostrovsky, Mikhail Sholokhov, Alexander Serafimovich, Boris Polevoy and others remain unshakeable — and serve as both an example and a warning.

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox