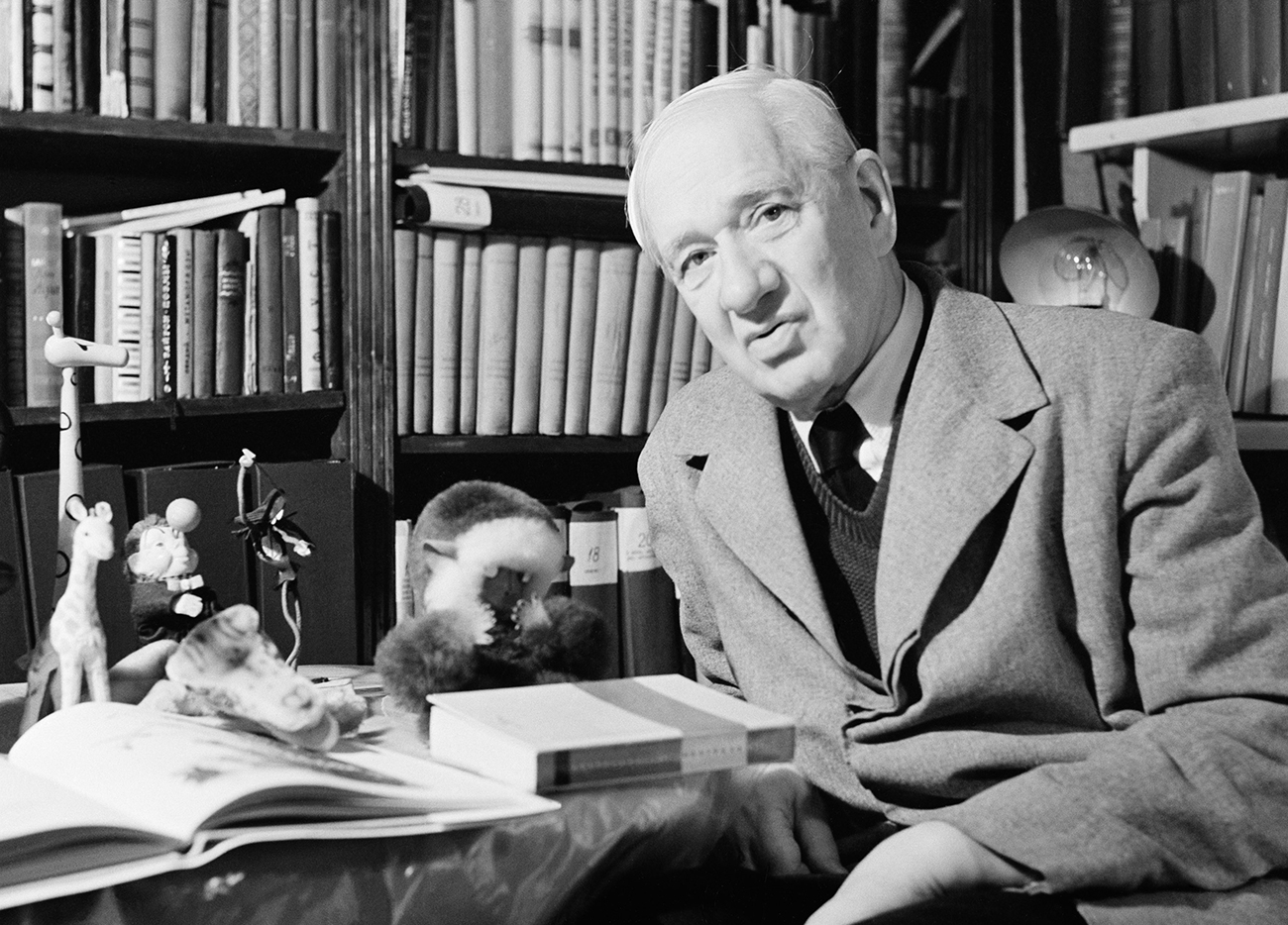

Korney Chukovsky in his study.

Vladimir Savostyanov/TASSThere are very few people in Russia whose youth was not influenced by the works of Korney Chukovsky. His poems and tales are read and reread so often they’re practically imprinted on the collective memory of the nation. The renowned children’s author still tops the bestsellers lists, despite passing away in 1969. Perhaps the secret of his enduring popularity is that he never moralized, was exceedingly jovial, and truly loved children. His books are imbued with a belief that good will triumph over evil, and wherever he went crowds of adoring children followed. However, Chukovsky was forced to overcome a number of obstacles in his life so he could continue writing his much-loved fiction.

Korney Chukovsky was born in St. Petersburg and later went to school in Odessa. However, he was forced to leave after only five years, expelled for his “lowly origin” (his mother was a maidservant in his father’s house). The young Korney studied by himself, read a lot, and taught himself English and French.

In 1901 Chukovsky started writing articles for the Odesskiye Novosti newspaper. Two years later he was sent to London as the paper’s correspondent. By the writer’s own admission, he was a bad journalist: Instead of attending parliamentary sittings, he would spend whole days in the Reading Room of the British Museum, devouring the classics of English literature.

When Chukovsky returned to Russia during the 1905 revolution, he was swept up by the events and started publishing the satirical magazine Signal, for which he was later arrested but acquitted thanks to his lawyer’s efforts.

Chukovsky was an active translator from English into Russian. He was the one who introduced Russian readers to Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, and Rudyard Kipling, and he would later be awarded the honorary title of Doctor of Letters from Oxford University (the gown is still displayed in the museum dedicated to him in Peredelkino).

However, Chukovsky found fame as an author of poems and tales for children rather than a translator. “One should write for children as well as one does for adults, only better,” he used to say. His poems “The Crocodile”, “Moydodyr” (roughly translated as “Wash-‘em-Clean”), and “The Monster Cockroach” quickly became popular and are still read to Russian children. Chukovsky was also one of the first people to start writing for very young children.

Suddenly from Mummy's bedroom,

Crooked-legged, old and lame,

Straight towards me came the

Wash-stand,

And he scolded as the same:

"Oh, you nasty little slacker!

Oh, you naughty little sqirt!

There's no chimney-sweep who's

Blacker,

There's no pig as fond of dirt!

Take a look into the mirrow.

(An excerpt from Wash-‘em-Clean, translated by E. Felgenhauer)

He firmly believed that the purpose of the storyteller was, above all, “to cultivate humanity in the child at whatever price – this marvellous ability to worry about other people’s misfortunes, to rejoice at other people’s joys, and to experience another person’s destiny as one’s own.”

At the same time, Chukovsky began studying child psychology and children’s speech. He described his observations of their verbal creativity in the book From Two To Five, which Japanese teachers, for instance, regard as one of the best studies of child psychology.

Unfortunately for Chukovsky, even children’s stories came under scrutiny by the Soviet authorities. In the 1930s a hate campaign initiated by Nadezhda Krupskaya, the wife of the USSR’s founder Vladimir Lenin, was launched against him. It was claimed that his format and content did not fully correspond to the aims of Soviet pedagogy. The author was deeply affected and subsequently could not write for a long time.

The main character in The Monster Cockroach (1925) reminded some readers of Joseph Stalin. The tale is about how “a terrible giant, a redheaded and moustachioed cockroach” appears in the animal kingdom and begins to intimidate everyone, demanding that they give him small animals for dinner. The animals turn into a trembling, fearful herd until a sparrow comes along and eats the cockroach. Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, arrested during Stalin’s purges, extended the metaphor by writing in his “Stalin Epigram” in 1934: “His cockroach whiskers laugh, and the tops of his boots shine.” But the question as to whether Chukovsky himself was portraying the Soviet leader remains open.

Chukovsky did not accept many things in Soviet society. He was the only Soviet writer to congratulate Boris Pasternak when the latter was awarded the Nobel Prize. On discovering Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s talent, Chukovsky was the first person in the world to write an ecstatic review of his Gulag novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and allow the author to stay at his dacha when he was being persecuted. Chukovsky also made efforts to defend the poet Joseph Brodsky, who was put on trial for “parasitism.”

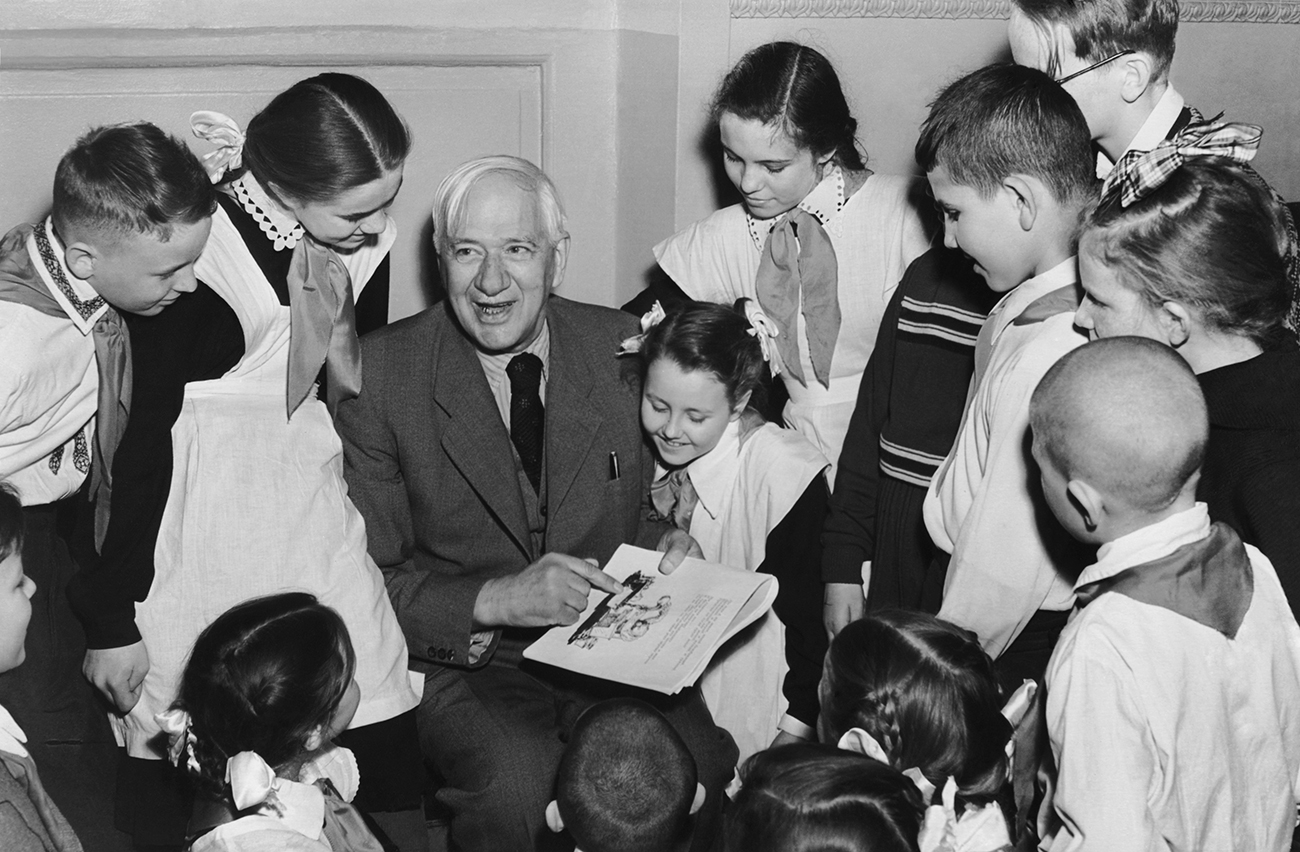

Korney Chukovsky (C) reading out his fairy tales at the Children's Book Week in Moscow. Source: Alexander Batanov/TASS

Korney Chukovsky (C) reading out his fairy tales at the Children's Book Week in Moscow. Source: Alexander Batanov/TASS

Later Chukovsky started working on retelling the Bible for children, but the project became very difficult due to the state’s anti-religious ideology. The whole of the first print run of the book The Tower of Babel and Other Ancient Legends was destroyed by the authorities, and it only became available to readers in 1990.

From 1938 onwards, the author spent more and more time at his dacha in the writers’ colony in Peredelkino near Moscow. Chukovsky had a magnetic effect on children, and when he went out for a walk, he was always followed by a group of local kids. He opened a library for them in Peredelkino with his own money; it still endures today, one of many legacies left by one of Russia’s foremost storytellers.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox