Russian culture and Soviet education left a deep imprint on Tagore

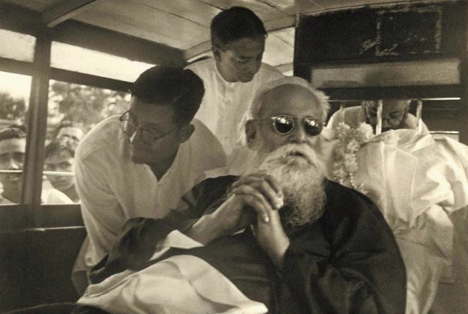

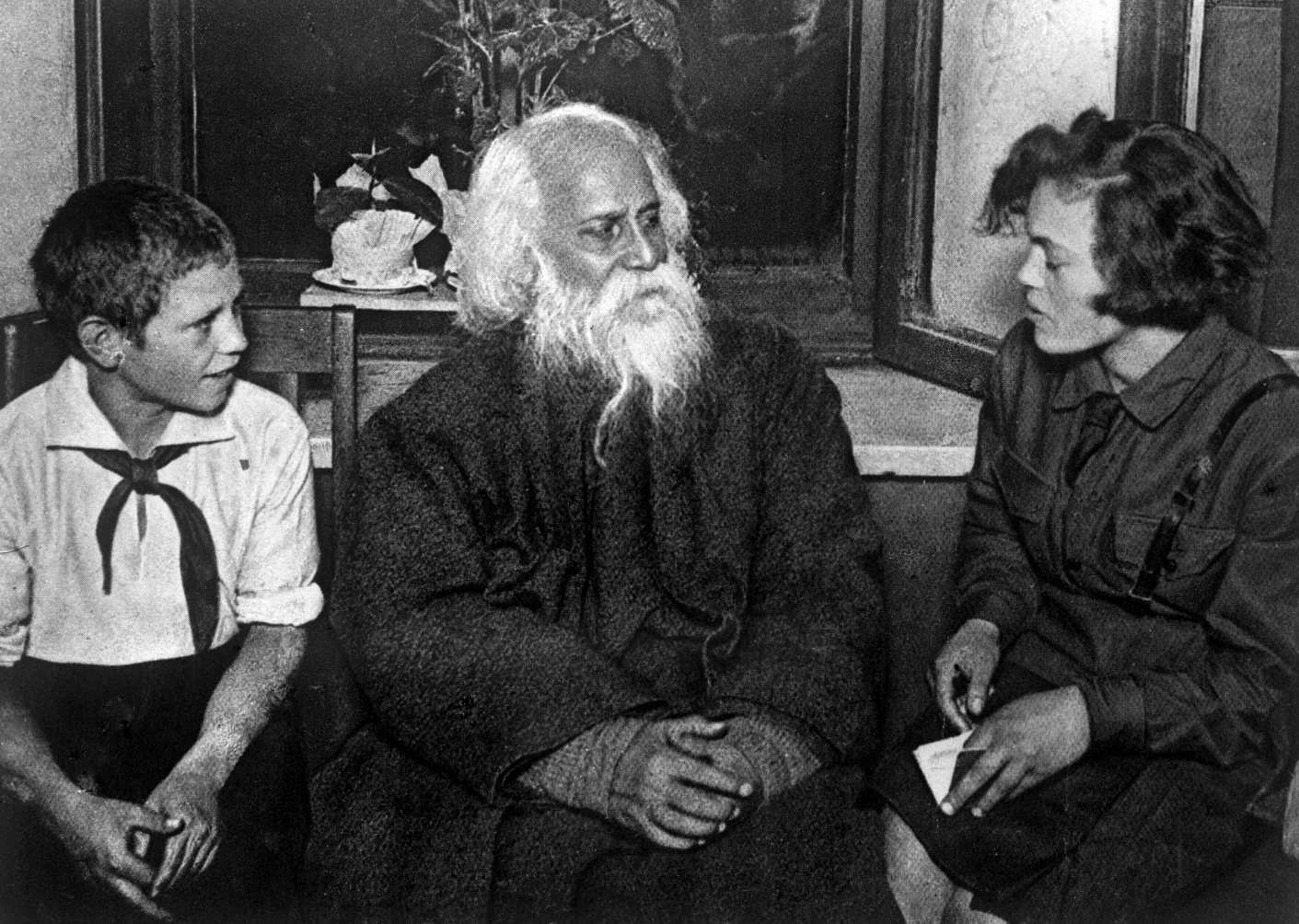

Indian poet and educator Rabindranath Tagore with Soviet schoolchildren.

RIA Novosti“On August 7, 1941, in Calcutta, a man died. His mortal remains perished, but he left behind him a heritage, which no fire could consume. It was a heritage of words and music and poetry, of ideas and of ideals and it has the power to move us today and in the days to come. We, who owe him so much, salute his memory…” This is how the famous film director and author Satyajit Ray described the great humanist, poet, writer and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, who is being celebrated this year to mark the 155th anniversary of his birth.

Last year, Russia commemorated another momentous date associated with the name of the great poet. September 2015 marked 88 years since Tagore’s visit to the Soviet Union (11-25 Sept 1930)

Tagore was known and loved even back in pre-revolutionary Russia. His poems were translated and republished on numerous occasions and actively promoted by Russian symbolists. In 1917, several translations of his famous collection Gitanjali (An Offering of Songs), which won him the Nobel Prize for Literature, were simultaneously released, including those edited by future Nobel Prize recipient and writer Ivan Bunin.

The memoirs of Nicholas Roerich attest to Tagore’s popularity in Russia: “Gitanjali came like a revelation. The poems were read at gatherings and at private ‘at homes’. Only true talent could create such a precious mutual understanding. Now everyone at once became imbued with love for Tagore. It was evident how most contradictory people, the most irreconcilable psychologists were united by the call of the poet.”

The tradition of poetic translations of Tagore into Russian continued later as well, with Boris Pasternak translating his works in the 1950-1960s and Anna Akhmatova doing the same in the 1960s.

The Soviet government decided to publish the collected works of Tagore in 1926. His poems and reviews of his work began appearing in many Soviet magazines.

In his article “The Indian Tolstoy”, Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Soviet people’s commissar (minister) of education, stated, “Tagore’s works are so full of colour, subtle spiritual experiences and truly noble ideas that they now constitute a treasure of human culture”.

Tagore tried on several occasions to visit Soviet Russia, but it proved to be a difficult venture to pull off. By late 1917, all ties between Russia and British India had been cut off.

While travelling in Europe in September 1926, the poet met with Alexander Arosyev, the Soviet Union’s Ambassador in Stockholm.

“You can’t imagine how long I have wanted to come to your country, which I love for its literature. And now that your people have become completely new and different compared to how they used to be, as my friends tell me, I am even more eager to come there. I want to get to know your music, your theatre, your dances and become acquainted with your literature,” Tagore said during the meeting.

In Berlin, Anatoly Lunacharsky personally extended an invitation for Tagore to visit the USSR. A flurry of activity began at all levels to prepare for the long-awaited guest. A special commission was set up and all Soviet missions were required to provide all necessary assistance for the poet’s trip. Soviet society also got involved in preparations for the meeting with the writer. Academic Sergei Oldenburg wrote, “When we meet the great Indian poet here, we will be meeting a person who, in Bengali words, has said what we all understand and feel”.

Tagore arrived in the Soviet Union on 11 September 1930.

“The sole purpose of my trip to Russia was to learn about the methods for spreading education and its results. I had very little time,” Tagore wrote. No matter before what audience Tagore spoke, he always emphasised why he had undertaken this trip, “I am not a politician. My sole purpose in life is enlightenment”.

On 14 September 1930, Tagore visited the first commune of pioneers named after Alisa Kingina, an orphanage. “Upon entering the orphanage, I saw that a group of boys and girls had assembled in two rows along the stairs in solemn silence in order to greet me. Once I entered the room, they sat down around me as if I was also from their group,” Tagore recalls. The children told him about their lives and studies. Tagore sang a song in Bengali called Jana Gana Mana, which later became the national anthem of the independent Republic of India. The poet was moved by his reception. In the pioneer guestbook, he wrote, “I shall always remember the wonderful evening I spent with these pioneers. I learned much from them that will be extremely beneficial to my people in India, for which I am grateful to them. I wholeheartedly feel sympathy for these young builders of the fate of a people and wish them success. R. Tagore”.

Tagore was struck by the scope of the cultural construction underway in the Soviet Union. “If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I could have never believed that in just ten years they have not only led hundreds of thousands of people out of the darkness of ignorance and degradation and taught them to read and write, but also fostered in them a sense of human dignity. We need to come here specifically to study the organisation of education,” Tagore wrote in his letters.

He was amazed by how a people who had carried out a revolution, endured dreadful famine and a bloody civil war could so actively visit art galleries, museums and theatres. This aspect was extremely important to the poet, as art was the foundation of his educational system in Shantiniketan.

He wrote with delight of the Tretyakov Gallery. “In Moscow, there is a renowned collection of paintings called the Tretyakov Gallery. In just one year, from 1928 to 1929, it was visited by approximately three hundred thousand people. The building does not have enough room for everyone who wishes to visit, therefore people sign up in lines before the weekend,” he wrote.

The overcrowded theatres left an indelible impression on Tagore. “In earlier times, the theatres were only open to the royal family and the nobility. Today they are packed full with people who till recently went around in filthy rags, barefoot, dying of starvation, living in constant fear before God, seeking any favour they could with priests, worried about the salvation of their souls and having been infinitely humbled, lying in the dirt at the feet of their masters”.

In September 1930, an exhibit of Tagore’s work opened at the State Museum of New Western Art featuring more than 200 watercolours. “An exhibit of my paintings was organised in Moscow. Needless to say, the paintings are unusual… yet the people came in endless crowds. Five thousand people visited the exhibit in just a few days,” he wrote.

The exhibit of paintings was a huge success among Muscovites. Soviet artists presented Tagore with the gift of a marble mask of Tolstoy, which is stored at a museum in Shantiniketan.

Tagore’s visit ended on 24 September 1930 with a festive concert at the Pillar Hall of the House of Unions, where the most important state events were traditionally held. Russia’s best singers and dance ensembles took part in the concert. The author’s poems were read from the stage of the Pillar Hall in Bengali.

Tagore shared his impressions of his trip to the Soviet Union in articles that comprise the collection ‘Letters from Russia’. These letters were written to relatives and friends during his trip and published in Bengali in the ‘Probasi’ magazine. In 1934, the English translation of Letters from Russia was banned, after Tagore’s criticism of the British administration concerning the eradication of illiteracy in India, which he compared with the policy of the young Soviet government. The English translation of Letters from Russia only saw the light of day after India was granted independence.

In the USSR, Letters from Russia was only translated into Russian for the first time in 1956. In addition, the publication excluded two of the fifteen letters, in which Tagore made negative comments on some aspects of Soviet life. Way back in the 1930s, Tagore foretold the political processes that would take place in the country at the end of the twentieth century. Speaking about the imminent collapse of Bolshevism, Tagore wrote, “It is possible that in this age Bolshevism is the cure, but medical treatment cannot be permanent; the day when the regime prescribed by the doctor is lifted will be a celebratory one for the patient”. He also prophesied the fate of socialism in the USSR: “… they cannot rely upon what they ultimately built in a short time with the use of cruelty since this construction is not capable of bearing the burden of eternity,” he wrote.

The poet was critical of the lack of freedom in the Soviet Union. In an interview with Izvestia newspaper, he said, “I must ask you: do you think fomenting the minds of the people you educate with anger, class hatred and vengeance in relation to those you consider enemies will be beneficial to your ideals? The freedom of thought enables one to grasp the truth, while fear kills it… Together with all mankind, I hope that you will not call into being the evil spirit of violence and cruelty, which it will then be too late to stop”.

In his letters and interviews, Tagore tried to speak objectively about the economic and cultural achievements of the Soviet Union. He managed to identify several positive aspects of the new government, while not overlooking the shortcomings.

“After my trip to Russia, today I am leaving for America,” he wrote at the end of one of his letters. “But the memory of Russia continues to dominate all my being. The thing is the other countries I have visited did not stir up my imagination in the same way. Their business-like energy is scattered around various types of activities, be it politics, hospitals, schools or museums. And here… everyone is united by common aspirations. Such a profound unity of souls is impossible in countries where property and energy are separated into personal interests”.

Tagore remained interested in the Soviet Union until the end of his life. Speaking on Indian radio on 8 May 1941, he again noted the Soviet Union’s successes in education.

“In the Soviet Union, I saw genuine efforts being made to combine the interests of different nationalities living on its territory. Tremendous funds are spent on people’s education here”.

The article was first published in 2012.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox