Dmitry Likhachov: The spiritual leader of the USSR in its twilight years

It is impossible to fully imagine what a 22-year-old young man, who had been leading quite a sheltered life, must have felt in a communist hell that arose on the ruins of a monastic heaven. Photo: Academician Dmitry Likhachev at home in Leningrad, USSR. 1987

Yuri Belinsky; Oleg Porokhovnikov/TASSIt is common knowledge that in order to win recognition in Russia, one has to live a long life. Dmitry Likhachov’s life story largely confirms this axiom. Despite the fact that already in the 1970s he was considered to be the country’s best literary scholar, Likhachov won public recognition only during the perestroika years. He was nearly 80 at the time…

Likhachov was born in 1906 into the family of a St. Petersburg engineer. <> It was his memory of the life “prior to the disaster” (as he referred to the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917) that was perhaps one of the things that later helped him not to despair. Unlike those who did not have first-hand experience of “the old times,” throughout all the years of his Soviet life Likhachov very well remembered that life could be different. This memory broke up the socialist reality and prevented him from losing himself in it. Was it perhaps this memory that gave him the strength to survive Soviet rule?

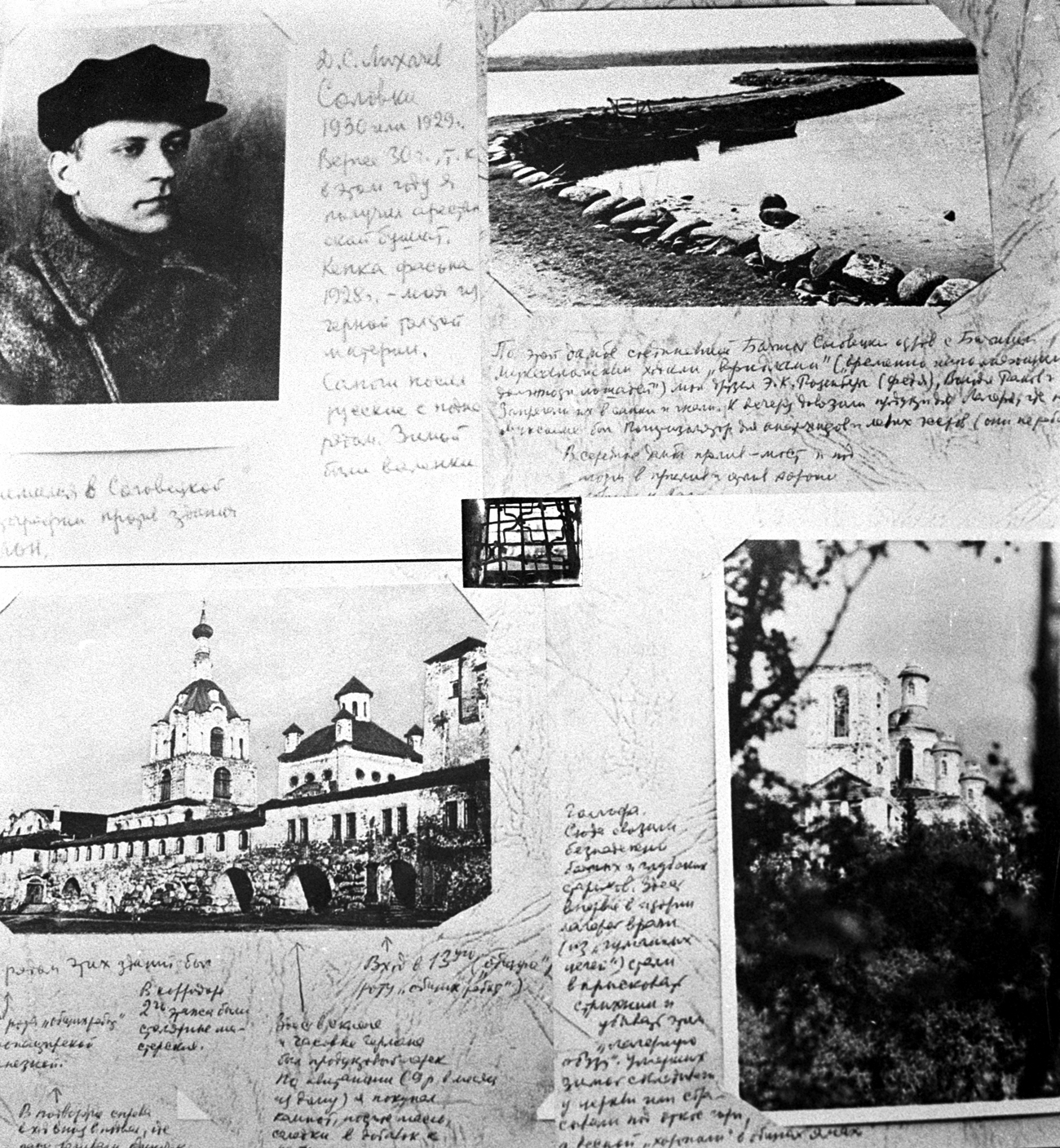

Upon graduation from university (in 1928), Likhachov found himself in a concentration camp on the Solovetsky Islands. It is now hard to understand how one could be given a prison sentence for one’s love of letters (the accusations against him were based on a report Likhachov had written called “On certain advantages of old Russian orthography”), but that is exactly what happened.

It is equally impossible to fully imagine what a 22-year-old young man, who had been leading quite a sheltered life, must have felt in that hell. A communist hell that arose on the ruins of a monastic heaven. The lost paradise of the monks was more than just a metaphor. When the islands were home to a monastery, it did have some quite tangible heavenly features, like the tropical fruit that monks used to grow in their greenhouses there, near the Arctic Circle. The greenhouses were heated by hot water that was used at the local candle-making facility to whiten the wax.

The lessons of Solovki

It was in Solovki that he first realized what death meant. Death came very close when his parents came to visit him in the camps. Likhachov found himself on the list of those prisoners whom the prison authorities had been given the right to execute “as a warning” for the others. Having been tipped off, Likhachov did not return to his barracks that night. Hiding in the log shed, all through the night he heard the firing squad at work. In the morning, when the executions were over, he realized that he had survived.

Likhachov later said that was the moment when he became a different person. He stopped being afraid, and that was an escape to freedom. He thanked God for every day he lived because he realized that from then on every day was a gift. Likhachov never compared himself to Dostoyevsky, who also had been awaiting execution, but one cannot help thinking of this comparison.

A stand at the 'The Solovki Convict Camp' exposition displaying pages from the photograph album of Dmitry Likhachov, Gulag convict in 1926-30 and future renowned historian. The captions are made in his hand. Source: Vladimir Fedorenko/RIA Novosti

A stand at the 'The Solovki Convict Camp' exposition displaying pages from the photograph album of Dmitry Likhachov, Gulag convict in 1926-30 and future renowned historian. The captions are made in his hand. Source: Vladimir Fedorenko/RIA Novosti

War, siege and human nature

After being released from the camps in 1932, Likhachov found a job as a proofreader. "Time misplaced me,” he recalled half a century later. “When I could do something, I was sitting twiddling my thumbs as a proofreader, whereas now, when I get tired so easily, it inundates me with work." In 1938, he started working at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Russian Literature, the famous Pushkin House, where he spent the rest of his life. Likhachov worked for over 60 years at the institute, which became his second home.

It was while working at Pushkin House that he lived through the Siege of Leningrad. There, like at the Solovki camp, life broke into two poles: "In hunger people revealed their true selves, bared themselves, freed themselves of every flippery: Some turned out to be wonderful, unparalleled heroes; others, villains, scum, killers and cannibals. There was no middle ground. Everything was for real. Heavens opened and God was there. Good people clearly saw him. Miracles were happening." These are lines from his book Reminiscences, without exaggeration, a great book.

The years after the war saw the publication of works that brought him international recognition. He carried out research on the poetics of Old Russian literature and its genres, and charted its development. He wrote about Leskov, Dostoyevsky – the list would take too long... One could not say that he was the No. 1 scholar in any of these areas. It is just that he touched most of them in a truly Mozart-like manner: at once elegant and indisputable. There is no sophistry in his works, they are written in a clear and calm language because a profound thought does not require any ornament.

A new spiritual leader

The ascent of Likhachov’s star is generally associated with the talk he gave at the Ostankino TV studio in 1986 (as part of a cycle called "Russia's outstanding writers" – RBTH). It was more than just a talk given by a famous academic. On that day, the country discovered a new spiritual leader. Or – to be more precise – a new type of a spiritual leader. In the Middle Ages, that role was performed by saints and in the 19th century by writers. In the late 20th century, it fell on an academic: such must have been the nature of that period.

I remember him well on the morning of Aug. 19, 1991 (the first day of the attempted coup against Gorbachev in Moscow – RBTH). At that early hour, Likhachov was the only one at work. "What bastards! he exclaimed. For some reason, I found that pithy epithet reassuring. Later – and in a more academic form – Likhachov expressed the same sentiment to tens of thousands of people gathered in St. Petersburg's Palace Square. He was 84 at the time.

Above courage I would probably put another of his qualities – independence. Surprisingly, not all courageous people are independent and therefore, ultimately, courageous enough. That happens when a person becomes a hostage to their reputation. To the point of view of their circle. To public opinion in general. Likhachov never felt himself a hostage: He was always free.

Dmitry Likhachov at his summer house in Komarovo, Leningrad Region, Russia. Source: Vsevolod Tarasevich/RIA Novosti

Dmitry Likhachov at his summer house in Komarovo, Leningrad Region, Russia. Source: Vsevolod Tarasevich/RIA Novosti

Enjoying a good relationship with Gorbachev, Likhachov nevertheless – and without a moment’s hesitation – sent a telegram to the Kremlin protesting against the Soviet troops seizing the Vilnius TV tower. When, however, the ethnocratic nature of the Baltic states became evident, he found some very harsh words to say about them, which – incidentally – was quite at odds with the “democratic” repertoire of the time.

His obviously democratic way of thinking notwithstanding, he was least of all prepared to accept the vaudeville part of “the founding father of Russian democracy,” which was sometimes imposed on him. It was most probably driven by this understanding of his default role that at the start of the Kosovo war an American TV crew came to interview Likhachov on his thoughts about the crimes committed by the Serbs. That was several months before his death. The indomitable academic suggested talking instead about crimes committed by America. He was not afraid of being excluded from the ranks of “progressive society.” He had lived such a long life that he had the right to have his own interpretation of progress.

Published in an abridged version with the permission of the author.

Read more: Eugene Vodolazkin's 'Laurus': Timeless tale of a medieval saint

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox