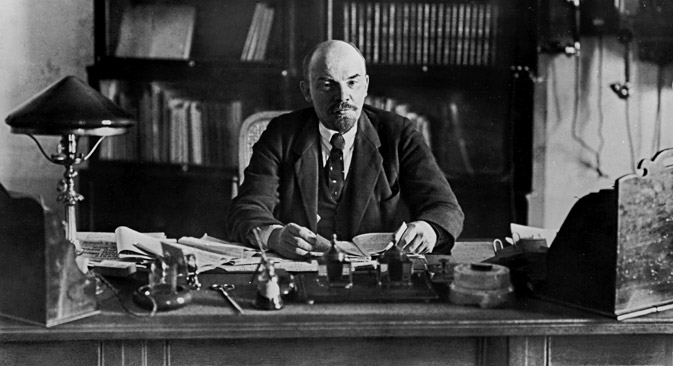

“There is no end to the acts of violence and plunder which goes under the name of the British system of government in India,” Lenin pointed out in his work 'Inflammable Material in World Politics'. Source: Denis Evstafev / RIA Novosti

It was the first Russian Revolution, in 1905, that fired up the imagination of Indian revolutionaries. Mohandas Gandhi regarded it as “the greatest event of the present century” and “a great lesson to us”. India was also switching to this “Russian remedy against tyranny,” Gandhi said.

The revolution made a big impact also on the minds of Indian revolutionaries who, unlike the ‘Moderates’ and the ‘Extremists’ of the Congress party, intended to get absolute independence by adopting revolutionary methods as practised by Russians.

The Bengalee newspaper declared in a May 25, 1906 editorial: “The revolution that has been affected in Russia after years of bloodshed...may serve as a lesson to other governments and other peoples.”

The Yugantar issued a threat: “In every country there are plenty of secret places where arms can be manufactured.” It advocated the plundering of post offices, banks and government treasuries for financing revolutionary activities. The newspaper also observed that “not much physical strength was required to shoot Europeans”.

The Indian Sociologist said in its December 1907 issue: “Any agitation in India must be carried out secretly and the only methods which can bring the English to their senses are the Russian methods vigorously and incessantly applied until the English relax their tyranny and are driven out of the country.”

These incendiary articles had an immediate impact, and within a year bombs were exploding and bullets flying across India. On April 30, 1908, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose threw a bomb on a carriage in Muzzafarpur in order to kill Douglas Kingsford, the chief presidency magistrate, but by mistake killed two women travelling in it.

Praising the bomb throwers, the newspaper Kal wrote: “The people are prepared to do anything for the sake of Swaraj (self rule) and they no longer sing the glories of British rule. They have no dread of British power. It is simply a question of sheer brute force. Bomb-throwing in India is different from bomb-throwing Russia. Many of the Russians side with their government against these bomb-throwers, but it is doubtful whether much sympathy will be found in India. If even in such circumstances Russia got the Duma, then India is bound to get Swarajya.”

Chaki committed suicide when caught and Bose, just 18 years old, was hanged. Bal Gangadhar Tilak – known as Gandhi’s political guru – defended the revolutionaries and demanded immediate self rule. He was arrested and a British kangaroo court sentenced him to six years in a Burma jail.

Days after Tilak’s trial, Russian leader Vladimir Lenin published an article titled 'Inflammable Material in World Politics'. He wrote that the British, angered by the mounting revolutionary struggle in India, are “demonstrating what brutes” the European politician can turn into when the masses rise against the colonial system.

“There is no end to the acts of violence and plunder which goes under the name of the British system of government in India,” Lenin pointed out. “Nowhere in the world – with the exception, of course of Russia – will you find such abject mass poverty, such chronic starvation among the people. The most liberal and radical personalities of free Britain…become regular Genghis Khans when appointed to govern India, and are capable of sanctioning every means of “pacifying” the population in their charge, even to the extent of flogging political protestors!”

Blasting the “infamous sentence pronounced by the British jackals on the Indian democrat Tilak”, Lenin predicted that with the Indians having got a taste of political mass struggle, the “British regime in India is doomed”.

“By their colonial plunder of Asian countries, the Europeans have succeeded in so steeling one of them, Japan, that she has gained great military victories, which have ensured her independent national development. There can be no doubt that the age-old plunder of India by the British, and the contemporary struggle of all these ‘advanced’ Europeans against Persian and Indian democracy, will steel millions, tens of millions of proletarians in Asia to wage…a struggle against their oppressors which will be just as victorious as that of the Japanese.”

Lenin and Gandhi

Lenin and Gandhi were at opposite ends of the revolutionary spectrum. They differed not only in their national and individual goals but also in the means they advocated to achieve such goals.

Irving Louis Horowitz writes in The Idea of War and Peace: The Experience of Western Civilization that despite their differences, the very fact they were both leaders of masses of mankind in great nations place them in a kinship.

India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, has indicated the character of this relationship of Lenin to Gandhi: “Almost at the same time as the October Revolution led by the great Lenin, we in India began a new phase in our struggle for freedom. Our people for many years were engaged in this struggle with courage and patience. And although under the leadership of Gandhi we followed another path, we were influenced by the example of Lenin.”

When Gandhi said that “nations have progressed both by evolution and revolution”, and that "history is more a record of wonderful revolution than of so-called ordered progress” he demonstrated a community of mind with Lenin that went beyond the simple coincidence of political careers,” writes Horowitz.

Then there is also the Gandhian definition of socialism that Lenin frequently emphasised – the view that socialism is more than a transformation in economic relations, but a transformation in human psychology as well.

Horowitz notes that both Gandhi and Lenin were distinguished by a fierce devotion to principle, while at the same time revealing large reserves of flexibility in the political application of these principles. “Thus, the pacifist Gandhi could even agree to the utility of national armies, small in size to be sure, in times of national crisis; while Lenin could see the utility of middle-class parliamentarianism in the development of class forces. Even in personal characteristics they had much in common. Each of them eschewed personal comforts, practicing instead an asceticism geared to the achievement of their ends.”

Trotting a different path

Leon Trotsky, Russian revolutionary and the founder of the Red Army, however, felt Gandhi was a fake freedom fighter.

In An Open Letter to the Workers of India, written in 1939, just before World War II broke out, he wrote: “The Indian bourgeoisie is incapable of leading a revolutionary struggle. They are closely bound up with, and dependent upon, British imperialism….The leader and prophet of this bourgeoisie is Gandhi. A fake leader and a false prophet! Gandhi and his compeers have developed a theory that India's position will constantly improve, that her liberties will continually be enlarged, and that India will gradually become a dominion on the road of peaceful reforms. Later on, India may achieve even full independence. This entire perspective is false to the core.”

According to Trotsky, never before in history have slave owners voluntarily freed their slaves. If the Indian leaders were hopeful that for their cooperation during the war the British would free India, they were grossly mistaken.

With uncanny foresight, Trotsky predicted: “First of all, exploitation of the colonies will become greatly intensified. The metropolitan centres will not only pump from the colonies foodstuffs and raw materials, but they will also mobilise vast numbers of colonial slaves who are to die on the battlefields for their masters.”

Trotsky believed India’s exploitation would be redoubled and tripled in order to rebuild war-torn Britain. “Gandhi is already preparing the ground for such a policy,” he wrote. “Double chains of slavery will be the inevitable consequence of the war if the masses of India follow the politics of Gandhi….”

All of Trotsky’s predictions would have come true if the rebel Indian National Army hadn’t driven a stake of fear through British hearts. The 1946 revolt of 20,000 Indian Navy ratings and the very real possibility of the Indian Army and Indian Air Force joining the revolt finally hastened the end of the most genocidal empire on the face of the earth.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox