On the Trans-Siberian

At the Vladivostok train station. Photo by Errol Chopping

We’d heard about the Trans-Siberian railway running all the way across Russia and several years ago, when we asked Valeriya if she regularly used it that way she was aghast.

"No way. Do you know it takes 7 days?"

The Trans-Sib idea just lingered in our minds. We were too busy to do much about it then. When we got the chance to go we figured it was now or never.

We knew the railway station well, it’s almost right in the centre of Vladivostok and just adjacent to the port. Downtown celebrations always included at least one large ship docked there which I remember sounding its horn in the middle of the fireworks.

We’d also visited the monument on the platform, which marks the distance to Moscow.

The distance to Moscow. Photo by Errol Chopping

No Google for us. No travel agency, no translators, and no $15000 Australian dollar cost either. As well, most people, especially tourists, go in the direction Moscow to Vladivostok and have a major itinerary and lots of English-speaking fellow travellers. Not us.

We were there, on the spot and intending to head West, from the place the locals consider the start of the journey. We just turned up at that very special Vladivostok railway station on a warm afternoon in September. We strolled through the doors and into the main waiting room. That turned out to be wrong and we ventured out again. Around the side and in the lower door got us to the ticket sales room. We spoke to the woman there.

We spoke to the woman there. Photo by Errol Chopping

I’m sure it could be done with just signals, but by then we were total experts! Well, anyway, we could manage these three words:

билеты, Москва, Пожалуйста (Tickets, Moscow, Please).

There were three classes. First class had two beds per compartment, food and full bathrooms. This was the kind of carriage that tourists use. Kupe (the 2nd class) had four beds per compartment and the compartments were separate and closable. You have to share, but sharing is what life’s about. In platskart, there were six beds and the compartments were open. We chose kupe.

A deal was done, a credit card produced, a little paperwork and lots of great advice. I’m sure it was good also to buy the ticket like we did, at the source. There were no extra layers, no intermediaries, no money changers, nor agents. The price reflected this too. Not $15000, but just $600 Aussie dollars for the whole 7 days. Laughing.

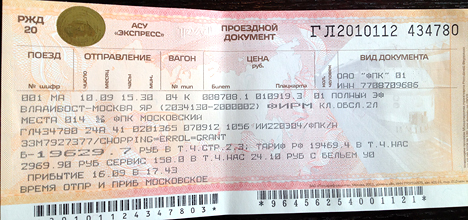

A pretty impressive ticket. Photo by Errol Chopping

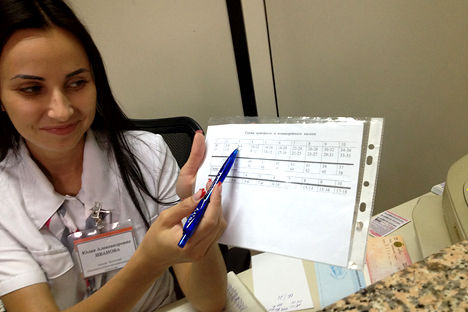

A kind of excitement grabbed us when we got the ticket, which was pretty impressive. It noted the train, the class, the date and time, the carriage and compartment, and our name. Whoa, the departure time is 3:30 this afternoon. We’d better hurry. She saw our problem.

"No no, this train runs on Moscow time." and she wrote 22:30 (the local time equivalent) on the ticket border with that dark blue pen of hers. Later we got used to using the clock inside the train, and the timetable there. The whole trip runs entirely on Moscow time and in Vladivostok, that’s 11 zones away.

So we had plenty of time to get to the supermarket. We bought noodles, grapes, biscuits, coffee, sausage, sweets, soup, nuts and so much more. We had time that night also to host a farewell dinner in the Republic restaurant and bar. It’s an airy and informal place, enjoyable and social too. Plates of wedges and calamari were common property. We chatted with Natalia, Roman, Nick, Veronika, Stephanie, Alex, Oleg, Alesandra and others and enjoyed some quiet beers and finger food.

At 10pm on that warm evening, we arrived on the platform, easily found carriage number 4 and our compartment, and chose the top two bunks of the four available. That turned out to be a good choice actually. The top bunks tend to stay as beds for the whole trip and also adjacent to the top bunks is a large storage area for food and bags. The lower bunks become beds during the night, and there’s no need to climb down from them using the door handles, but by day they are seats and the occupants feel a need to share. On balance the top bunks were best for us.

On the Trans-Sib, once you enter the carriage, you slip into a time warp. It’s like stepping into a boat that sails off into the sea, far away from reality. You are free from noise and rush. You spend some time looking out the window, watching the towns pass by. Early on you sneak sideways looking at your fellow passengers without speaking. You get used to interpreting the timetable and noting the many stations and stops along the way, and the times of arrival.

The timetable. Photo by Errol Chopping

There is time to think. Time to read and write. You sleep while the train forges ever westwards, clacking and rocking as it goes like a lullaby for rest. Out the window the cities give way to forests. You see birches and rivers and villages of dachas. In the distance, sometimes a highway. When you look into the forests, you daydream of what it would be like to be there when it’s snowing. There are workers’ huts every few miles along the track. Each one is small, about 2 metres by 1.5, with a sloping roof for the snow. Inside and along one side is a metal stove and its chimney reaches up and out into the open. You imagine how much these huts are necessary for survival in winter.

Forests, birches and rivers. Photo by Errol Chopping

Each carriage has a проводница (railway conductor, pronounced provodnitsa). She knows her passengers and prowls the corridor between stops. She keeps the carriage clean and tidy and makes the bathrooms clear and clean each day. At each stop she stands in uniform on the platform, by the carriage door, like a soldier guarding the entrance. She makes the stops more formal and she’s feisty too.

Although like everyone on the train, we had our own supplies, and there was plenty of sharing offers, there was also fresh food for sale on or adjacent to each platform at the stops. We were not surprised to see noodles and soft drinks there but we also found икра (caviar, pronounced Ikra) and пельмени (dumplings, pronounced pelmini). Also, with a little foreboding, we sampled the smoked рыба (fish, pronounced rebu). "I’ll eat it now. If I’m still alive in the morning, you can have some."

Smoked fish. Photo by Errol Chopping

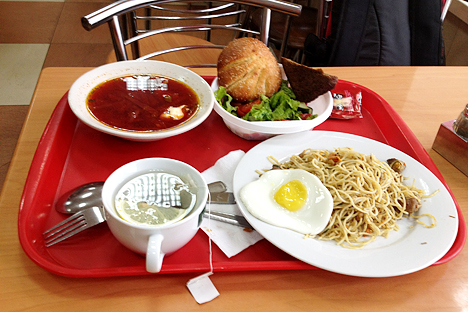

There was a buffet car. Old world, comfortable and well provisioned. The hostess had her own table, overflowing with accounts and paperwork near the counter and she was lodged there and unmovable. She ruled the roost. She barked orders from time to time at the others, a cook and a waiter. She supervised. A well-preserved woman of undetermined years also worked there. She worked with the passengers too. Always a friendly greeting, always a dinking partner.

"Will you buy me a vodka?" You could probably get more if you were in the mood.

In the buffet. Photo by Errol Chopping

On tourist trips there would be many excellent parties in that buffet, lots of toasts and songs well into the night, but as far as we could tell, as the only two non-Russians on the train we were often the only two customers in the buffet. One cup of coffee and a small salad lasted us 4 hours there and 4 hours was just enough time to pass by Lake Baikal.

Lake Baikal. Photo by Errol Chopping

More time to think and sleep and read and write. Stations came and went. Goods trains flicked past too and their 65 carriages just added to the background sounds. Our compartment lost its married couple and we talked for a day with a young mining engineer. When he left, a middle-aged woman locked us out for an hour or so, then left as quietly as she had arrived. We observed a young woman wrapped in a blanket who slept for two days.

When the last compartment in the carriage became empty I took up residence there, to write. I eventually noticed the unhappy provodnitsa but she figured I didn’t know it was out of bounds, and so she lets me stay. Eventually, Oleg joined me. He was 66 years old (I know this) and had been on trains all his life. He worked on steam, on diesel and electric and could identify the numbers beside the tracks.

Oleg and the family tree. Photo by Errol Chopping

"The obelisk is coming soon, marking the line between Asia and Europe," he told us, and we watched and counted.

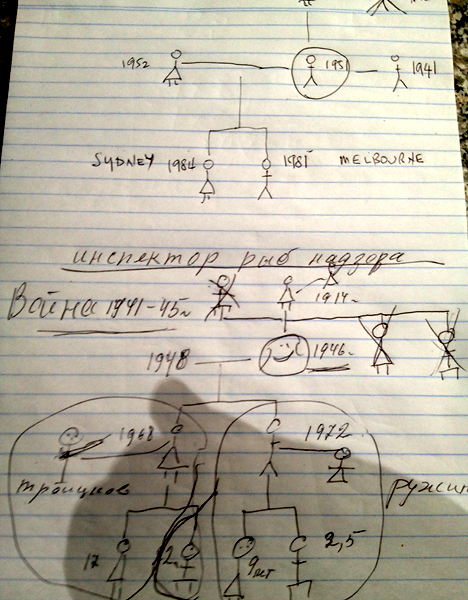

Even without the language, we communicated. I remember drawing my family tree on a writing pad. Women with dresses, men with legs, dates of birth and lines of genealogy. So simple. When I turned it to him his face lit up and in return he drew his family tree in detail.

The family tree. Photo by Errol Chopping

At Eкатеринбург (Catherine’s city) he dashed away. Out of the train and onto the platform, and up the flights of stairs leaping two at a time. Across the ramp he went and through the waiting room (I imagine the locals thinking what’s the hurry). Down into the township he ran, into the shops. We were worried. "He’s gone?"

Within the allocated time he was coming back, up the outer flights again and back through the station rooms. We caught a glimpse of him again above the platform, holding something. He was skipping down the steps this time and found our car again. The provodnitsa glowered as he lurched inside. He was carrying a bottle of cognac.

What he couldn’t know was that while he was away, we had a guest arrive. The compartment we were minding became occupied by a lady. When Oleg got back she was there. When Oleg showed the bottle of cognac she was pleased!

Cognac toasts. Photo by Errol Chopping

All together we drank a toast to the Trans-Siberian, and talked more about the kinds of things one talks about with fellow travellers. Where there’s a common language it’s easy, but even when there’s not, there’s no barrier either.

Before we knew it, we arrived at Yaroslavsky railway station in Moscow. As we passed through the barriers all the passengers disappeared. Some to friends, some to appointments, some to further travel or home. We were met and whisked away to the Taras Bulba restaurant with Sergey. Where did those 7 days go?

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox