It was an ordinary day in Blagoveshchensk.

It was an ordinary day in Harbin too. We were there. Well, we’d just arrived actually, the day before, and the very next morning were on the train, northbound. Friends in Harbin were confused and they shook their heads "What?Why are you are going to Blago?" "What’s there?" We were determined. We had a contact there: Olga. We were going. I’m glad we went. It was ordinary, but also charming, and I think close to the essence of a Russian provincial city: unhurried, easy, friendly, unpretentious, clean, truly Russian, and authentic.

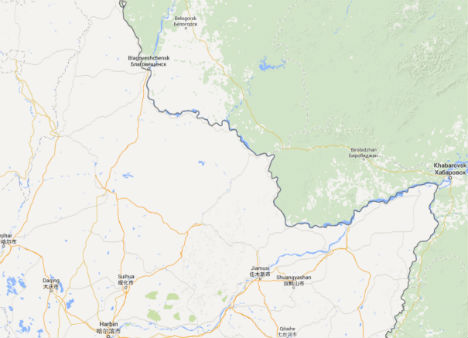

North bound to Blagoveshchensk. Source: Google Maps

We were all night in that train, but without a problem. We talked; we drank coffee, ate noodles and bantered on. Eventually we slept. In the morning we looked out and ventured through to the concourse.

Through to the concourse. Source: Personal archive

We were in Heihe, on the Chinese side of the Amur River. I’ve never seen so many taxis in one place at one time. Well this was an ordinary day in Heihe.

In Heihe, on the Chinese side of the Amur River. Source: Personal archive

It was a short taxi ride to the port. There we lined up like many of the others. A boat awaited just ahead and on the river. We waited in the queue. There was a little more fuss than usual because most of the travellers were Chinese going into Russia or Russians going back. A border city (well, a twin city in a way) has these exchanges and we were not common travellers. At an international border, there’s always a delay and we had become used to it. We weren’t used to the extreme delay coming back though, but more of that later.

The sun was shining, the sky blue, an ordinary day for a boat ride on the Amur River. That river is deep and fast and the boat was churning in the current. It waited for us. Onboard we looked over the side. The river was moving faster than I have ever seen before. I thought about what would happen if I fell overboard and tried to swim. I think I would be carried away with the water. A good swimmer could only counter that current for about a minute. For me it would be less. No wonder the boat was churning.

An ordinary day for a boat ride on the Amur River. Source: Personal archive

The boat was churning. Source: Personal archive

Off the boat and along the shore by the railway tracks, and the Blagoveshchensk port is like any other. A large empty room and we were through the immigration gate without too much trouble. An ordinary day in the city.

We walked for about 10 minutes, no tourists, no market, no noise. Just a sleepy provincial city with elegant buildings, cars and taxis like any other. Down by the river we could see across to China, and on our side see Russian ladies sunbathing.

The civic centre. Source: Personal archive

After the civic centre, tall and grand, and the Lenin memorial, we headed off to the centre of town and something to eat.

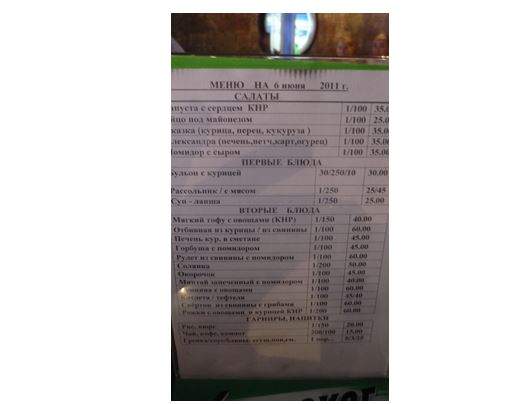

I’ve written of this experience before, but it’s worth repeating here. We were such novices then and had virtually zero Russian language. We ventured into a café in the main street. It was a friendly place but no waiter, no proprietor and no customer spoke English and we had a menu to contend with. It was a simple menu I know, but for us, at that time, it was daunting. I recall that I could make out only one word: ‘Soup’, and that was not going to be enough.

A simple menu. Source: Personal archive

Some of you will know the drill. If you’ve eaten in foreign restaurants before and had to deal with language issues then the scenario might be common. It goes like this: I point arbitrarily at some item on the menu. I have no idea what it is. Like sticking a pin into a map. "один?" she says, meaning "one?" "нет два" say I, meaning "no thanks, two." And so we dance this verbal and culinary dance. I point, she enquires, I suggest two.

Eventually I finish, probably after 4 or 5 circuits, and I wait. She brings back a chicken and ham cutlet, one bowl of minestrone soup, a bread roll, a ripe tomato salad with sour cream, and a beer. Wow. I could have been extra lucky with my arbitrary pointing, but there’s the other probable reason: she realises I am stuck, she knows I am hungry, (well I am in a restaurant), she is smart. She just brings me a sensible meal and we are both happy.

Olga. We mustn’t forget Olga. She’s at the Amur State University.

Outside the restaurant there’s a taxi rank and we walk towards the lead car. In it is a fairly mature gentleman. Grey hair, baseball cap, T shirt, denim vest. We negotiate again. We say every Russian word known to us (not many in those days) and he’s confused. Finally a simple solution. On the back of a name card I write a single symbol ‘?’ and hand it to him, along with the University name. His eyes light up and he smiles. ‘Ah’. He writes on that card ‘310’. A little over $10 Aussie then. It’s a deal and we get in.

Oh Olga if you only knew. The ride from hell.

We were off, down the main street faster than I’d every been on a public road. We were perched in the back of that taxi, up high too, and without any seat belt. We lurched from right to left and back again, bashing our heads together and looking for a grip. Through a roundabout we sailed, some other car was coming around it too and as we lurched again he shot his thin and blotchy arm out through the window and challenged the other driver with his middle finger, while driving faster than I thought was possible too and steering with the other hand. The words he used I now know, but I won’t write them here. We didn’t tell Olga about them either. Eventually we rocketed down a straight and semi rural road and up to brick gates, and stopped in the middle of a large puddle. We hopped out. We weren’t complaining about any wet feet either. No puddle was going to stop us getting out and we were thankful to be alive.

The Amur State University is like any other. A cafeteria with coffee that’s too hot, students, stairs, lecture rooms and impressive buildings. Upstairs and in an office overlooking the quadrangle is Olga, our contact and a charming host. With her help we see the whole place.

The museum is particularly interesting with some artefacts from a relatively recent past and some, like mammoth tusks, from more ancient times. In the corner there’s an earthen bed, the site of first human existence in the place. I remember asking the professor and he simply said "We think it was one of our students."

Olga. Source: Personal archive

Tracking back to the port and immigration hall is a blur now. I don’t even remember risking another taxi ride but I suppose there must have been one. In the hall were 40 or so travellers, and us. We waited our turn again. As each one approached the booth we’d wait about 10 minutes.

We finally approach, hand over our passport and card and visa. Like always, same old. Then our officer hesitates, lifts the phone and makes a call. This is a bit unusual, I think. She speaks into the phone. She hangs up. She says nothing to me. We wait. I observe her. Large, friendly, but with a stern demeanour. I am tempted to ask if there’s a problem but I’m too timid. My colleague is in for the same treatment. In fact, his officer is also waiting. She leisurely flicks through his passport. Like mine, it contains many used pages and many visas and stamps. The phone rings. She speaks into it again. She hangs up. She looks at me. She flicks through my passport again. The adjacent officer flicks through my colleague’s passport again. We wait. I look around. There are about 20 people waiting behind me and I’ve been at this window for 25 minutes now. They are getting twitchy. I look ahead. Yes, the boat's there. I know it’s the last boat for the day. If it sails without us what can we do? If we pass through after it’s gone we’ll have to pass back into Russia to get accommodation. We wait. The immigration phone rings again. She speaks into it. Nothing. I am starting to wonder if a red light has come up on her computer screen. She looks at me again but says nothing. My colleague’s officer is next door and in clear view. She flicks through his passport yet again. Page after page after page of visas and stamps. She says to him "You’ve been to a lot of places" He replies "If you marry me you can come too."

We are still waiting. Thankfully, the boat is waiting too. Maybe they know what we don’t. After another 25 minutes, the phone rings again. After she listens to it, she smiles. She waives my passport above her head to indicate to the woman next door. "They go through" she says, although it must be done by lip reading for the other officer. Stamp, click, stamp and she hands the documents back. As I collect them, finally I have the courage to speak, unlike my colleague who spoke before, my statement is pretty basic. I say "What was the problem?" She simply says "нет проблем." After 55 minutes total we are through.

We come back into China on that boat again without too much problem. The sun is setting as we meet our friends in a local restaurant and wait for the return train to Harbin. We drink Vodka, Kailua, Wine and tea. We’ve had an ordinary day in Blagoveshchensk.

Source: Personal archive

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox