The Bolshevik Revolution put an end to the Russian Orthodox Church’s proselytization in Korea.

ZUMA Press/Global Look PressIn 1897, the Russian Orthodox Church decided to establish a mission in Seoul. At the time, Russian influence in Korea was at its height and therefore, Russian policy makers saw the spread of the Orthodox faith as a way to further Russian influence and, as we would say now, “soft power” in Korea.

However, by the time the mission became operational, the political situation had changed decisively. Russian influence had been supplanted by Japanese influence. Nonetheless, there were many Russians residing in Korea at the time, so a mission (or, at least, a church) was needed.

There were hopes that the mission would be successful in proselytizing. Objectively speaking, the Orthodox Church has never been particularly successful in missionary activities, especially in East Asia. The only notable exception was Japan, where in the second half of the 19th century Russian missionaries succeeding in getting a rather significant following. Nonetheless, in the early 1900s Orthodox missionaries were encouraged by their success among ethnic Korean settlers in Russia.

Koreans began to migrate to Russia in the 1860s and many of them subsequently converted to Christianity.

This was often done under the assumption that such a conversion would make them less suspicious in the eyes of the authorities and would emphasize their newfound loyalty to the country they had settled in. At any rate, it was a success and encouraged the missionaries.

The head of the mission, Archimandrite Chrysanthos Shehtkofsky, arrived in Seoul in January 1900. He immediately started numerous new projects. In 1900-2, six new buildings were added to the mission along with church schools. The St Nicholas Church became operational in 1903.

The Russo-Japanese War interrupted the activities of the mission. French diplomats became the protectors of the mission buildings, while the employees of the mission were deported to China.

After the Russo-Japanese War, there were few opportunities for proselytizing and the number of Russian residents in Seoul shrank precipitously to around two or three dozen people (mainly consular officials and businessmen). Nonetheless, the mission still operated, supported by subsidies from the main church in Moscow.

By 1917, the mission had 12 Russian staff members and also employed 17 Korean schoolteachers. There were a few hundred Korean Orthodox Christians across the country – some of them were Korean migrants who returned from Russia, but the newly converted constituted a large majority. In 1912 the first ethnic Korean priest was ordained.

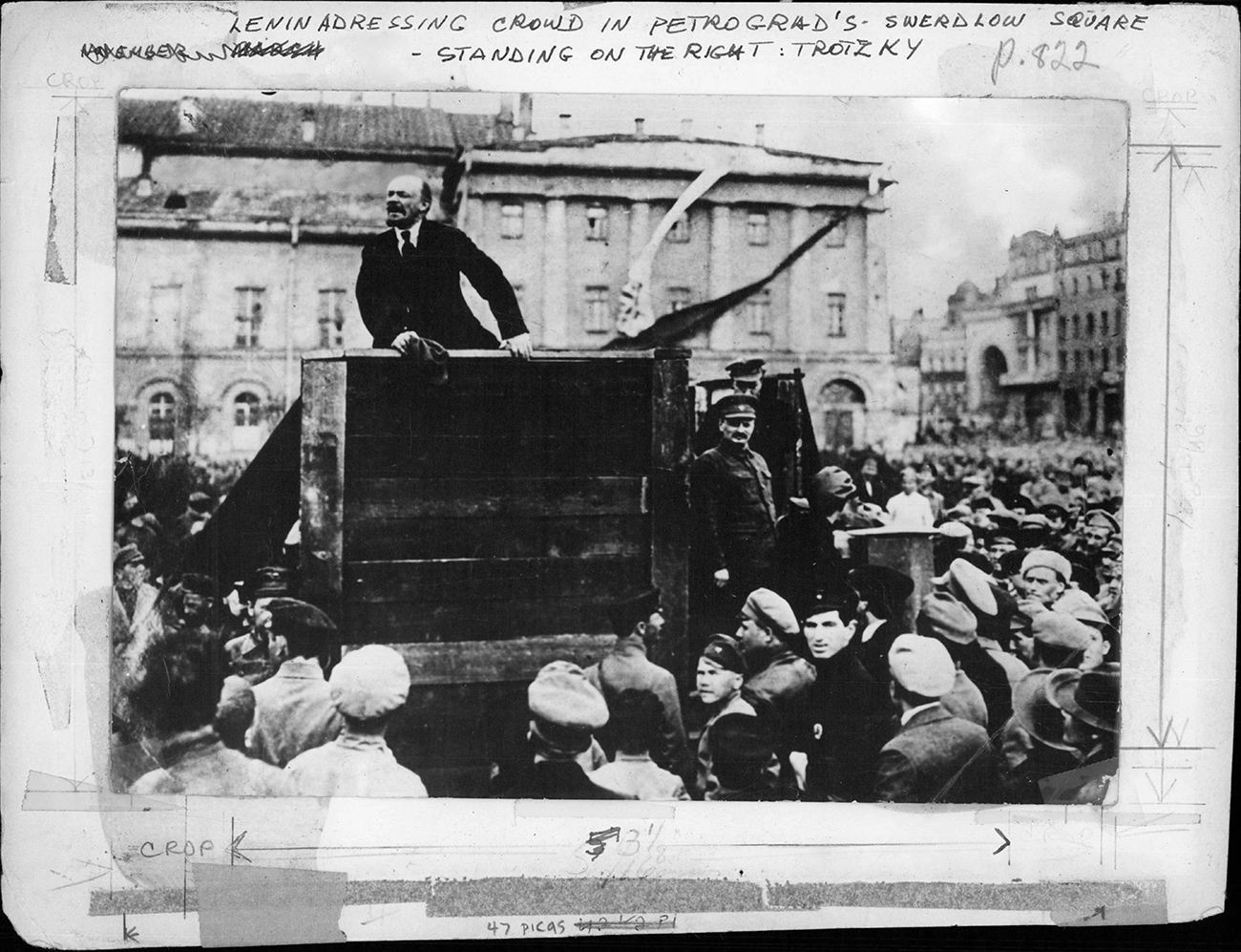

Predictably the 1917 October Revolution delivered a huge blow to the mission. The new Communist government took a militantly atheist stance at home and overseas and therefore, saw no reason to assist the ‘reactionary’ and ‘feudal’ activities of the mission.

Facing great financial difficulties, the mission had to downsize, so by late 1918, it had only one priest and two Korean staff members. Missionaries had to work on a small field owned by the mission to survive.

Some sympathetic outsiders, including the Anglican bishop in Seoul, provided them with some financial aid. It also helped that the mission had rather spacious buildings, which could be rented to outsiders.

The mission’s situation looked hopeless after the victory of the reds in the Russian Civil War. And in 1922, control over the mission was switched from Moscow to Tokyo, to the then head of the Japanese Orthodox Church.

And quiet flows the Han is a blog about the historical and contemporary interactions between Russians and Koreans. In most cases, but by no means always, political issues are studiously avoided by the author, whose major interest is everyday life, culture and the lives of individuals. In this blog, Dr. Andrei Lankov explores how Russian culture was (and is) seen in Korea. He talks about migration, inter-marriage and even cuisine.

Dr. Andrei Lankov, born in 1963, is a historian specializing in Korea. He is also known for his journalistic writings on Korean history. He has published a number of books (four in English) on Korean history. Having taught Korean history at the Australian National University, he now teaches in Kookmin University in Seoul.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox