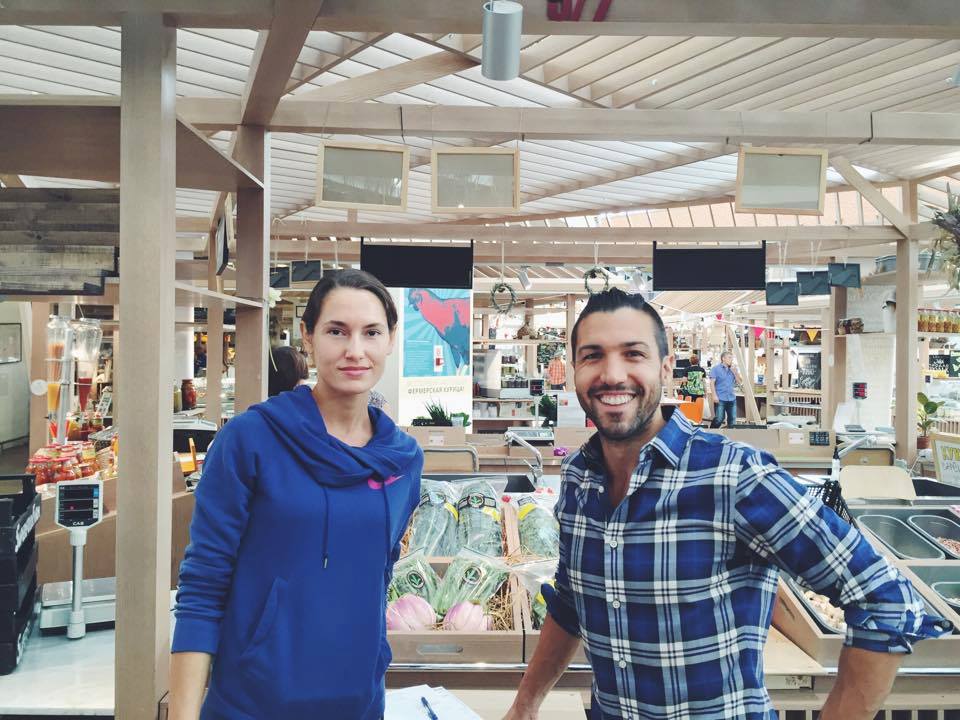

Olga Korogodina and Daniel Lawrence.

Personal archiveKale, the leafy green superfood that has taken over salads from Los Angeles to London, is making inroads into the Russian diet thanks in part to Daniel Lawrence and Olga Korogodina. The pair founded Superfood Farm in 2014 and today supply kale and other niche vegetables to a number of Moscow restaurants and retail chains, including the upscale Azbuka Vkusa supermarket and the farmers’ cooperative Lavka-Lavka. The U.S. Embassy in Moscow is also a client.

Lawrence did not set out to become a farming pioneer in Russia. An American investment banker specializing in financial markets, Lawrence came to Russia in 2010 intending to stay no longer than six months. However, he found life in Moscow “thrilling” and decided to explore long-term opportunities in Russia, supporting himself through business consulting and teaching English.

During a trip home to the U.S. in 2013, Lawrence came up with the idea of growing kale in Russia. The vegetable’s popularity had exploded in the U.S. and Europe, but was virtually unknown in Russia.

He decided to plant an experimental plot at his friend’s dacha to see how the vegetable would grow in the Russian climate.

About this time, Korogodina, who worked in real estate, decided to brush up on her English and started taking lessons with Lawrence, and she found the idea of introducing kale to Russia an exciting possibility.

Daniel Lawrence / Personal archive

Daniel Lawrence / Personal archive

Korogodina and Lawrence decided to launch a farming business together and in 2014 they began looking for a plot of land in the Moscow Region for their first large-scale planting.

“It was essential for us to find land with greenhouses already on it,” Korogodina said, “However, finding anything from ads was virtually impossible, so we just opened Google Maps in landscape mode and searched for greenhouses.”

Eventually Korogodina and Lawrence found a two-hectare plot of land in the Dmitrovsky district of the Moscow Region.

Korogodina and Lawrence invested $100,000 in Superfood Farm, mostly from Lawrence’s savings. Income earned from their regular jobs in Moscow also went into the farm.

“In the end we had to buy a bytovka [Ed: a small cabin temporarily installed at construction sites] and set it up at the farm,” Korogodina said. “We would work in it in the evenings and then sleep there before going to Moscow in the morning.”

“That lasted for two years,” Lawrence added. “Had somebody told me earlier that one can work so hard, I would not have believed him.”

Superfood Farm is an organic operation because Korogodina and Lawrence believe that the best quality and best tasting vegetables can be produced only by using organic farming methods.

“In the U.S. everybody knows what ‘organic’ means,” Lawrence said. “There are dedicated shops selling organic products and people choose for themselves whether to buy organic and pay slightly more or opt for regular shops with more affordable prices.”

Olga Korogodina / Personal archive

Olga Korogodina / Personal archive

In Russia, the trend of buying organic began only in the late 2000s and today farms with organic certificates account for only 0.1 percent of all farms in Russia, according to the International Foundation for Organic Agriculture (IFOAM). According to Ivan Rubanov, head of analysis at the State Duma’s Agriculture Committee, the main stumbling block for the development of organic farms in Russia is the lack of national standards and independent certifying bodies.

Andrei Khodus, the founder of the national certifying organization Eco-Control, seconded Rubanov’s assessment.

“At the moment, the title of an organic farm in Russia can be officially obtained as part of the existing voluntary certification systems, for instance that of the environmentally-friendly and biodynamic agriculture called BIO,” Khodus said, adding that in order to add eco-, bio- or organic to the name of a farm, its operations first need to be examined by bio-certifiers.

Organic farmers agree that the lack of clear rules for certifying produce as organic is a major obstacle.

“There are many unscrupulous producers in Russia who label their products as eco-, bio- and organic, but in fact they are nothing of the sort,” said Roman Gurov, executive director of the Organic Farming Union.

To address this problem, the state should get involved to support organic farmers and to stipulate clear rules set in laws, he adds.

High labor costs and smaller harvests also pose major challenges for organic farmers. The small scale of the farms makes organic produce from 30 to 200 percent more expensive to grow than non-organic produce, Rubanov said.

Today, in addition to Korogodina and Lawrence, the farm employs 10 people. Apart from two varieties of kale (curly and Tuscan black), Superfood Farm grows 30 varieties of tomatoes, peppers, lettuces, eggplant and herbs. They harvest produce nine months a year.

Currently, all proceeds are being invested back into the business. Korogodina and Lawrence expect to start turning a profit in 2-3 years.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox