IKEA's shopping mall in Khimki.

Ruslan Krivobok / RIA NovostiIn early August, searches were conducted in Swedish furniture giant IKEA’s Russian head office in Khimki (a town in the suburbs of Moscow where IKEA also has a shopping mall) in connection with an old land dispute. Two weeks later, a former IKEA manager, Joakim Virtanen, turned himself in to investigators, this time in connection with another controversy, related to the lease of electricity equipment. IKEA has been in litigation regarding these two disputes for over 10 years.

IKEA is an absolute champion in terms of the number of court cases it has had in Russia. The register of arbitration cases contains over 200 lawsuits against the Swedish concern, while the total number of court cases involving it has exceeded 560. All the other major retailers in Russia taken together would not have a tenth of this number of court cases between them.

The company itself is convinced that this is the result of its ambition to conduct honest business in the country and that other firms avoid such complications by paying bribes.

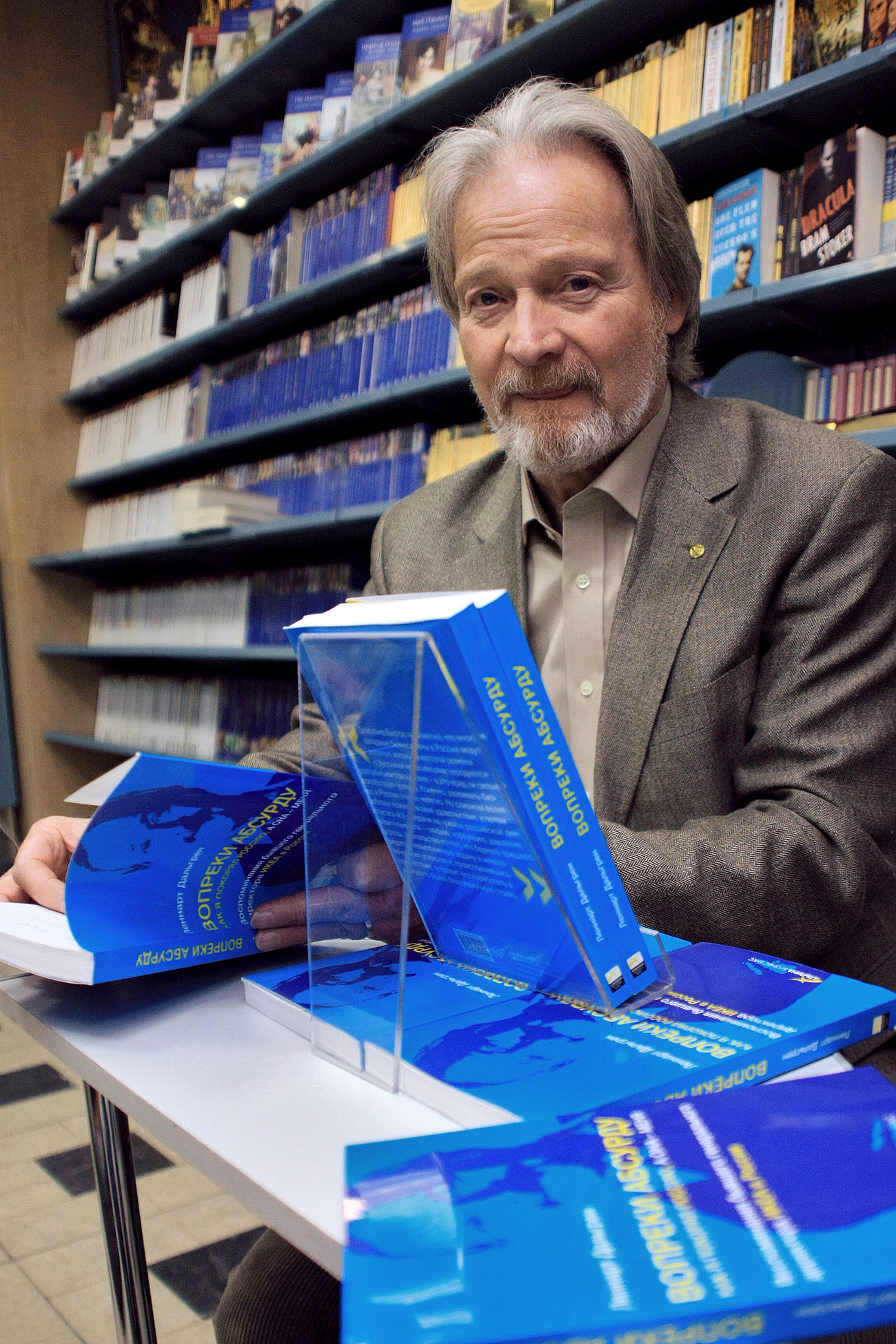

In 2010, Lennart Dahlgren, the former CEO of IKEA Russia, released a book called Despite Absurdity: How I Conquered Russia While It Conquered Me, in which he told the tale of what it costs to be true to one’s principles while surrounded by rampant corruption. The book named many people who obstructed its business, from the mayor of Khimki to the governor of the Moscow Region, and became a hit.

Lennart Dahlgren released a book called 'Despite Absurdity: How I Conquered Russia While It Conquered Me'/ Kommersant

Lennart Dahlgren released a book called 'Despite Absurdity: How I Conquered Russia While It Conquered Me'/ Kommersant

Market players, however, say that it is hard to be a saint while doing business in Russia and gladly cite examples of IKEA’s blunders.

To begin with, there are questions about the lawyer whom IKEA has chosen to represent its interests. The Lawyers and Business firm has represented the company in many lawsuits for several years already. In 2015, its owner, Sergei Kovbasyuk, defended IKEA in a class action lawsuit over a case of poisoning in the IKEA café, famous for its meatballs. Market sources maintain that the lawyer’s functions go far beyond that.

Kovbasyuk’s name became well-known in connection with a number of controversial cases. There were also media reports that Kovbasyuk used to work for the FSB (Russian Federal Security Service), hence his connections and astronomical fees. The lawyer himself has refused to talk to the press. Sources are convinced that his law firm renders services in so-called “special situations.” This euphemism usually implies corruption and corporate raiding as well as resolving “sensitive issues” with the authorities or other market players.

Sergei Kovbasyuk / Press photo

Sergei Kovbasyuk / Press photo

“When foreign companies do not understand the rules of the game in Russia, they hire intermediaries – legal and consulting groups or GR experts,” said Ilya Shumanov, deputy head of Transparency International – Russia. “These positions are highly corruptogenic and people who fill them are entrusted with resolving the most sensitive issues,”

Almost all the lawsuits are filed against the IKEA subsidiary that builds the company’s stores. In all countries, IKEA builds its shopping malls itself instead of renting premises. However, in Russia IKEA has come up against more problems than in other countries – primarily because it is hard to build things. (In the dealing with construction permits section of the Doing Business ranking, Russia is in 119th position out of 189.) This creates many opportunities for corruption.

The plots that IKEA was given for construction are mainly located on former collective farm land. “These plots have a tangled privatization history, with most cases being so old that it is often impossible to find all the related documents,” says the head of practice at the Infralex law firm, Sergei Shumilov.

For example, in Khimki the land was leased by the company, after which it was bought out, when suddenly in 2012 the former owner, while conducting inspections, discovered that it no longer had the land.

“Does this mean that no inventory was carried out for many years? And nobody knew or saw that this land is now the site of a major construction project that officials and the media are talking about. I personally find it strange, to say the least,” says Maxim Gladkikh-Rodionov, managing director of the Confidence audit firm.

In 2010, there was a corruption scandal in St. Petersburg involving Per Kaufmann, IKEA director for Central and Eastern Europe, and Stefan Gross, IKEA director for real estate in Russia. Both were sacked practically immediately. IKEA even decided to conduct an internal investigation to find out if any more of its employees were engaged in bribery directly or indirectly.

IKEA in St. Petersburg / PhotoXpress

IKEA in St. Petersburg / PhotoXpress

It turned out that a bribe had been offered by a Russian contractor and the top managers were guilty of knowing it but not preventing the crime. In exchange for the bribe, officials agreed to sign a fake acceptance certificate for electricity equipment in an IKEA shopping mall. Furthermore, the project had not even been approved.

One way or another, all these stories prompt lawyers to suspect that the company may be being targeted by some influential corporate raiders. “One gets the impression that the company is simply being strongly encouraged to ‘be like everybody else’,” says Gladkikh-Rodionov.

Given that the Russian market is of great significance for IKEA (the 11-percent rise in the company’s sales in 2015 was largely due to Russia and China), it would be justified to predict that the company will continue to have to resort widely to legal assistance.

First published in Russian in Kommersant

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox