A memorial plaque to the founder of “Zhigulevskoye” beer brewery and Austrian nobleman Alfred von Vacano in Samara.

Vladimir Smirnov/TASSMoving to Russia today and starting a business is tough and tricky, but is it really different from a few centuries ago? Many foreign entrepreneurs came to Russia in the 19th century, attracted by cheap labor and the lack of competition, but it still was difficult for them to adapt. They didn’t have anyone here – no friends, language skills or local knowledge. So, they did everything they could to fit in, including changing their name to the Russian manner. Would you be brave enough to embark on such an adventure?

Ludwig Knoop

Public domain“In every church there is a priest; in every factory there is Knoop,” goes a Russian saying from the 19th century. It’s not life advice, but a reference to one of the richest entrepreneurs of that time – Ludwig Knoop, a cotton merchant from Germany who was a pioneer in the Russian textile industry, and who received the title of “baron” from Alexander II.

Born in Bremen, Knoop started his career in the Manchester cotton exporting company, De Jersey & Co, and in 1839, at that time only 18-years old, he came to Moscow to work as an assistant to the firm’s agent in Russia. Knoop was young and energetic and knew exactly how to fit in: he knew that to do business in Russia one had to adapt to local life and get along with local businessmen, which often meant drinking in taverns, and he learnt to keep a clear mind while doing that!

The turning point in Knoop’s career happened in 1947 when thanks to the lifting of the British ban on the export of cotton machinery he got his first order from Savva Morozov, a Russian textile magnate, who asked Knoop to equip his cotton mill with English machinery.

England, which was a leader in the textile industry at that time, did not want to create competitors for itself in Russia, but Knoop managed to convince De Jersey & Co to extend a loan for machinery exports in exchange for future profits. The success of this first project led to Knoop building and equipping more mills, thus modernizing and re-equipping the textile sector in Moscow and neighboring regions that suffered from a lack of state support and bank credits.

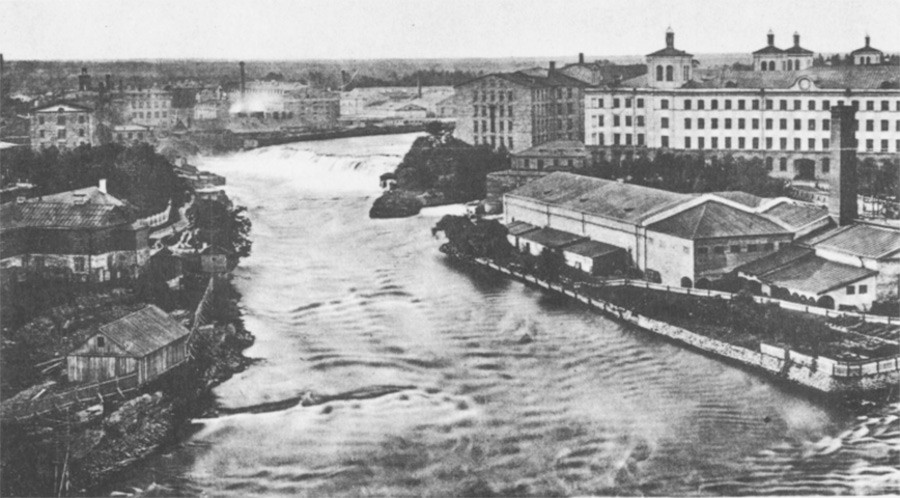

The Krenholm Manufacturing Company (1886)

Public domainAgents that could connect Russian entrepreneurs with foreign suppliers and provide loans were badly needed, so Knoop filled the void. In 1852, he opened his L Knoop & Co, and in 1856 he built the largest cotton-spinning mill in Europe on the island of Kreenholm in Narva (Estonia), and came up with a strategy that earned him a fortune. He offered his Russian clients to build a factory from scratch, equip it with English cotton machinery and staff it with English technical workers who maintained the machinery for a few years. He didn’t take cash or provide loans – instead he took a share of the newly built factory that made him a shareholder in dozens of textile companies.

Overall, he was responsible for equipping 187 cotton mills across the country, and owned the largest textile factory in Russia, giving him leverage to determine the prices of not only cotton but of all textiles sold in the country.

Later in life, Lev Gerasimovich, as he was called in the Russian manner, returned to his native Bremen but visited Russia occasionally to take care of business. He died in 1894, leaving 12 companies to his two sons, but those in Russia didn’t survive following their nationalization after 1917.

Ferdinand Theodor von Einem

Public domainThe young German entrepreneur, Ferdinand Theodor von Einem, came to Moscow in 1850 eager to achieve success in an unknown country. He began with production of lump sugar, and later in 1851 established a small business producing chocolate and sweets on Arbat Street. The enterprise went well: there were few competitors and demand was high, so he soon started thinking about expanding his business.

In 1857, von Einem met his future business partner, a fellow German, Julius Heuss, and together they opened a shop on Teatralnaya Square, and then a factory on Sofiyskaya Embankment in 1867. Von Einem hired locals from neighboring villages, gave them accommodation near the factory, and opened a canteen and a school for children who aspired to work in the factory. Einem also gave part of the profits to Moscow charities and to a German school for the poor and orphans.

One of the Einem chocolate ads reads "Well, try to take it away if you dare"

Public domainIndeed, there was no problem with revenue. The brand, “Einem,” earned wide public recognition thanks to a wide variety of products on sale, from cookies to fruits covered in chocolate, and which had eye-catching packaging made of silk, velvet and leather. Heuss was fond of art photography and used this knowledge in Einem’s ads and packaging design.

Such success led von Einem and his partner to expand production and open additional factories on Bersenevskaya Embankment (today, these buildings are known as Red October). In the early 19th century, Einem was one of the five largest and most famous confectionery brands in Russia, and in 1913 the company became an official supplier to the Imperial Court.

The Einem factories on Bersenevskaya Embankment (before 1917)

Public domainUnfortunately, however, Fedor Karlovich (as Einem was called in Russia) never lived to see this honor: he gradually handed control over the business to Heuss (who kept the brand’s name), and he died in 1876 in Berlin. According to his will, Einem was buried in Moscow, and his grave in Vvedenskoye Cemetary hasn’t been forgotten: there are always fresh flowers there.

Alfred von Vacano

Public domainThe founder of “Zhigulevskoye” beer and Austrian nobleman, Alfred von Vacano, was the sixth child in his family, and had aspired to brew beer since he was a boy. The Austro-Prussian War (1866), however, postponed his plans when he was drafted into the army, and then was injured and captured. He returned to his passion after the end of the war.

Eventually, von Vacano found himself in Russia, more specifically in Samara, where in 1880 he asked authorities to lease him land for his future brewery. It’s not exactly clear how he got to Russia and what he did here before that time, but one thing is certain – he got land that previously hosted another brewery, and he then built one of the most famous beer brands in Russia whose name is still known today.

Before coming to Russia, von Vacano learned the fundamentals of brewing in Germany and what is now Czech Republic, which allowed him to understand all aspects of the process. He eventually came up with his own unique recipe, and equipped his factory with latest technical innovations. He had a conveyer and transporter, plus an automatic beer tap. In addition, his factory had a steam boiler room with the largest storehouse of fuel oil in Samara. By the way, the apartments of his factory workers were the first in Samara to receive steam heating.

In 1881-1905, the volume of production at his factory grew 50 fold, and by 1911 he was the third largest producer of beer in the country, selling it across Russia, Central Asia and even Persia.

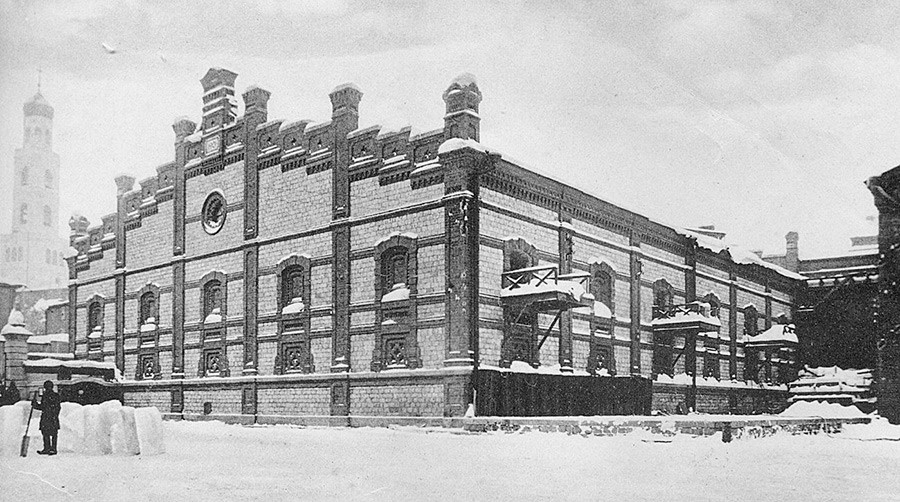

The "Zhigulevskoye” beer brewery (before 1918)

Public domainVon Vacano wasn’t only a good entrepreneur but also a generous philanthropist. He called Samara his second home and did his best to improve the city. He built the first power station in Samara, set up lighting in the factory, workers’ homes, the local drama theater and the city’s park. He used his private funds to develop sewage systems, and he gave one of his estates to the local orphanage. He also helped the Russian Red Cross and supported the veterans of the Russo-Japanese war. In 1899, he and his family received Russian citizenship.

With the start of the First World War, the production of beer stopped and the premises of the factory were used for military purposes. Von Vacano built a hospital for the city and promised to take care of all the expenses of caring for the injured until the end of the war. Despite his honorable work, however, the authorities had suspicions that his family members might work with Austrian and German intelligence.

His son, Vladimir, was an Austrian consul, and his daughter, Olga, worked in Vienna. Eventually, von Vacano, a 70-year old man by then, was accused of being a German spy and was exiled to the town of Buzuluk in the Orenburg Region together with his son Vladimir. There, he continued to manage his factory, but the Bolshevik’s rise to power in 1917 prompted many of his family members to flee to Austria.

The factory was nationalized and von Vacano followed his family to Austria where he spent the rest of his life. The factory in Samara remained, but following the unsuccessful attempts of von Vacano’s heirs to bring it back to glory in the 1920s it eventually was taken over by the authorities, together with the family’s brewing recipe. The brand “Zhigulevskoye” survived, but that is an entirely different story.

Did you know that there were other famous brands in Imperial Russia that have survived until this day? Check if any of these ring a bell.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox