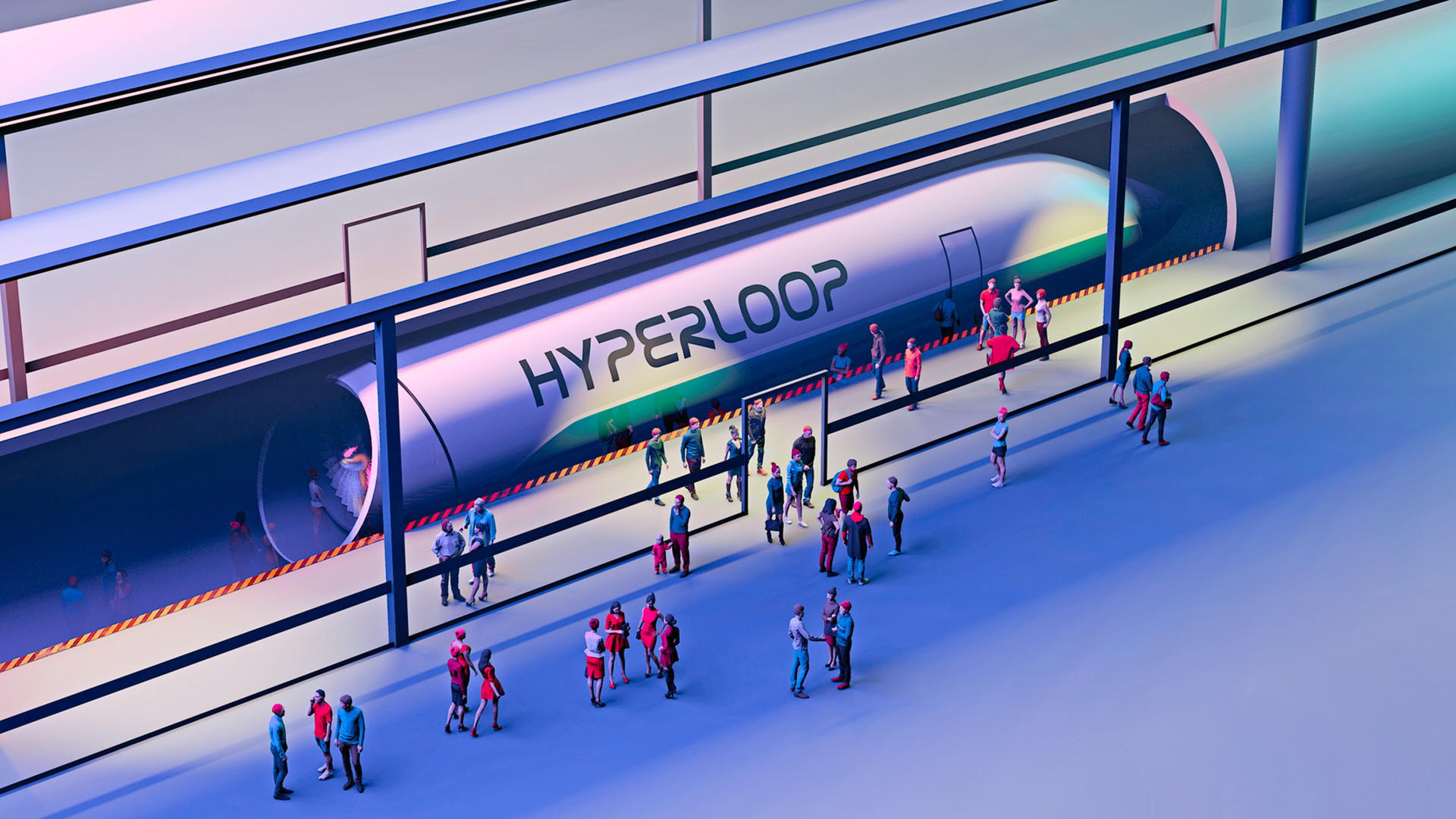

Russia. 2030. You arrivе at Moscow’s Hyperloop station, hop on a pod-like capsule and travel to St. Petersburg in just 33 mins. You barely notice the extraordinary speed of 745 miles per hour and comfortably relax while the capsule conveys you through a vacuum tube, closer and closer to Russia’s cultural capital. It’s the first Hyperloop system not only in Russia but also in the world - and you are one of its first passengers!

A tempting idea, right? First coined by Elon Mask in 2012, the Hyperloop has been on the minds of technology enthusiasts for a few years now and, in 2017, Josh Giegel, the co-founder of Virgin Hyperloop One, even suggested that Russia could become the first country to bring the project to life. But how viable is it for today’s Russia? And should we expect to see it any time soon?

The first steps to make the Hyperloop a reality in Russia were already taken in 2016-2017. Back then, Hyperloop One and Russia's Summa investment and trading group discussed plans to create a 40 miles-long cargo Hyperloop system connecting the Russian Far East with neighboring China (Zarubino-Húnchūn). Yet, following the 2018 arrest of its prospective investor and co-owner of Summa, Ziyavudin Magomedov, the project stalled and since then no further tangible progress has been made.

Amidst the talks about the construction of a new high-speed highway between Moscow and St. Petersburg, the Hyperloop idea resurfaced once again. Russian experts from the Institute of Natural Monopolies Research (IPEM) estimated that the proposed highway might actually cost more than a Hyperloop - 1.5 trillion rubles ($24 billion) against 1.18 trillion ($19 billion) - which makes it an alternative that might be also considered.

While a futuristic Hyperloop does seem more exciting than another railroad on the map of Russia, the experts also argue that the cost of this unique journey is unlikely to be cheap. They estimate the most affordable one-way ticket will cost at least 16,100 rubles ($257) or 13-18 percent of the average monthly earnings of ordinary people from Moscow or St. Petersburg. This means that for the Hyperloop project to be economically viable in Russia, it must be used by 2.4-7.6 percent of the wealthiest Russians every day - which is not at all enough for the authorities to seriously consider the project.

Other Russian analysts also don’t seem too enthusiastic about the future of the Hyperloop in Russia. While the project only exists on paper for now and it’s too difficult to assess its cost, it does look like an unprofitable business endeavor for now, says Gennady Nikolayev, expert at the Academy of Finance and Investment Management. “The problem is that at this point there is no way one can make this project economically viable. To increase the passenger capacity one has to increase the number of tubes, but this will make the project even more expensive,” he says. “It might be more appealing for China where there is a need to cater for vast passenger flow...There are no such problems in Russia and we often debate the viability of high-speed trains from Moscow to St. Petersburg - how can we seriously discuss the idea of a Hyperloop?”

Petr Pushkaryov, analyst at TeleTrade, is a bit more optimistic. According to him, even though it might not break even and be economically risky, the Hyperloop will surely be a great brand project for Russia which will attract global attention and draw tourists. “This will be the world’s first and only project like that,” he says. “But then, it will also be necessary to promote it in the right way.”

Overall, experts doubt that Russia is anywhere near becoming the first country to implement Elon Musk’s idea. Even if one doesn’t take into account its general economic unprofitability and suggests that foreign investors might get interested in funding such a project in Russia, there will be geopolitical factors that might put them off.

“Foreign investors will have to contribute large sums of money, which is risky given the [international] sanctions [Russia is currently subject to],” says Roman Alekhin, founder of the marketing group Alekhin and Partners. “Coupled with a worsening investment climate, state pressure on business and constantly changing tax rules, this might push investors to consider another country with more transparent ‘rules of the game’.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox