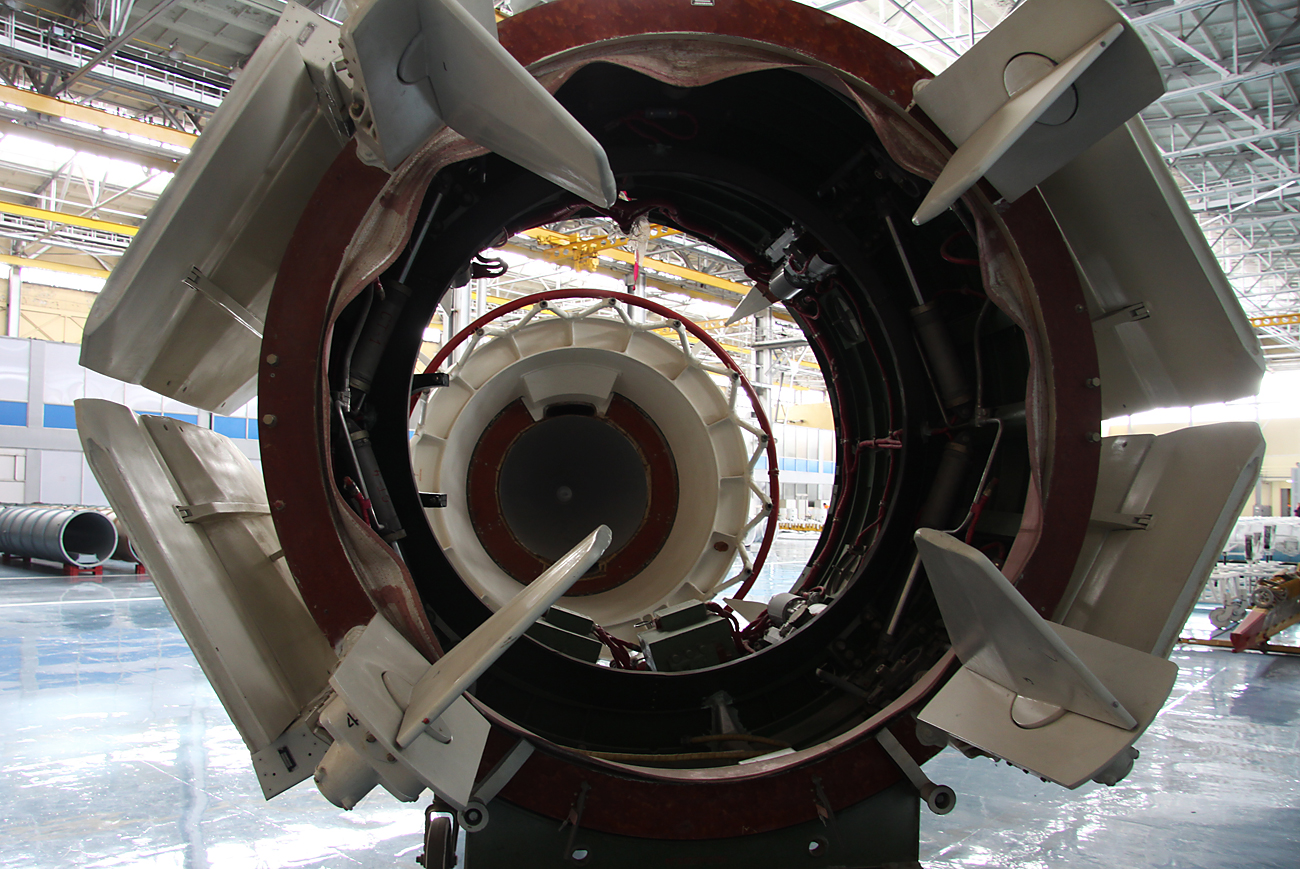

An antimissile of the A-135 Amur missile defense system under construction at the Avangard factory in Moscow.

Viktor Litovkin/TASSAs the fight for space enters an active phase and requires increasingly advanced technical innovations, Russia is developing weaponry capable of striking targets beyond the earth’s atmosphere, and the first rocket with these capabilities could be on the way.

In late August the deputy commander of the Russian Aerospace Forces, Lt-Gen. Viktor Gumenny, announced that the Russian military was to receive a long-range antimissile.

“This will allow air defense and missile defense troops to carry out any task set by the supreme commander and the defense minister within the set timeframe,” he told the Russian News Service radio station.

The new long-range antimissile was first mentioned in late 2015, after its successful flight tests. An image of the missile in a launch tube appeared in a corporate calendar produced by the arms manufacturer Almaz-Antey.

Information about the new Russian missile is classified. Even the exact name of the model is not being disclosed. According to open-source reports, the missile has no foreign equivalents. Its avionics have no equivalents in Russia, while its engine is designed to make the missile the fastest in the world.

According to the Aerospace Forces command, it will be a long-range missile – which may mean that its impact zone will include the whole of near space.

The history of Russian antimissiles capable of intercepting ballistic missiles and satellites dates back to the 1970s. Back then designers came up with an ambitious idea: The threat posed by the nuclear weapons of a potential enemy could be reduced to zero by countering it with a missile shield.

To rule out the very possibility of undermining the nuclear parity between the superpowers, in 1972 the USSR and the U.S. signed a treaty restricting their capabilities to create national missile defense systems. Those capabilities could be deployed only within the geographic boundaries of a set region. The Soviet Union used its nuclear umbrella to cover Moscow.

A 53T6 missile of the A-135 missile defense system, Sofrino, Moscow Region / PhotoXPress

A 53T6 missile of the A-135 missile defense system, Sofrino, Moscow Region / PhotoXPress

The main missile defending the capital was the 53Т6 model, known as Gazel in NATO classification. It operated on the same principle as its U.S. equivalents: It was a solid-fuel missile several meters long and fitted with a nuclear warhead.

However, the execution of the Soviet equivalent made it a truly unique design. With a mass of 10 tons and a powerful engine, it rose to an altitude of almost 100,000 feet (30 kilometers) in a matter of five seconds. Its 10 kiloton nuclear charge would blow up in the stratosphere, hitting enemy ballistic missile warheads.

More importantly, the designers envisaged a serious potential for upgrading the missile. This work took place in Soviet times and continued after the break-up of the Soviet Union. That is why today the 53Т6 continues to be a formidable opponent to low-orbit satellites, including those that form part of the global navigation system.

Yet as an anti-satellite weapon a missile has a number of shortcomings. In some cases, it may be more effective to use weapons that do not destroy the target but just render it inoperative. These include ground-based jammers: metal constructions set on a vehicle platform and packed with electronics that are deadly for satellites.

Space surveillance and missile defence system - Don-2N radar - located near Sofrino, Moscow region / Ivan Gushchin/TASS

Space surveillance and missile defence system - Don-2N radar - located near Sofrino, Moscow region / Ivan Gushchin/TASS

The Russian electronic warfare system for countering satellites in low circular orbits is equipped with special aerials, i.e. specially mounted electronic devices for receiving and transmitting signals. They hit low-orbit satellites in their Achilles' heel. If the system manages to suppress just a couple of weak signals, the whole satellite group becomes inoperative.

Latest tests have shown that the brainchild of the Moscow Institute of Radio Engineering Research has turned out to be even more effective than its designers anticipated. If deployed in the Russian Arctic, the electronic warfare system for countering satellites in low circular orbits could cover the space over the bigger part of the northern hemisphere.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox