Every two weeks one of the world’s spoken languages disappears. Extinction is usually something we associate with animals, but forms of communication are also dying off – out of 7,000 languages spoken worldwide today, 2,680 are endangered.

It’s impossible to trace the exact number of how many languages have already been lost over human history, but linguists believe that over the last five centuries, 115 languages have disappeared in the U.S. (280 languages were spoken at the time of Columbus), while 75 languages have been lost in Europe and Asia Minor.

Russia is not immune to this downward trend. There are 40 minority ethnic groups living in the country and out of 151 languages spoken here, “18 are currently in danger of disappearing, not having more than 20 elder native speakers left,” says Igor Barinov, head of the Federal Agency of Ethnic Affairs (link in Russian).

As he explains, Russia has lost 14 languages over the last 150 years, including five during the post-Soviet period, despite a state program started in the USSR to protect indigenous languages.

Increased migration and rapid urbanization are pushing many ethnic groups to change their traditional ways of life. People are increasingly adopting more dominant languages to ensure civic participation and economic integration. In Russia’s case, this means minorities are choosing to teach their kids Russian instead of their native tongue.

Russia’s North Caucasus is one region where indigenous languages are fading. “At the end of the last century, areas like Dagestan seemed to show no signs of the decline already visible in North Siberia and the Far East,” Rasul Mutalov, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), said. “Yet the situation has started to change over the last decade when people living in mountainous areas have started to migrate to the downcountry, to cities, and villages and increasingly started to speak Russian as a language of interethnic communication. The younger generations now don’t speak their native languages. Languages are dying right before our eyes.”

The Chelkans

The government of Altai RepublicThe Chelkan people living in Russia’s Altai Region are also abandoning their mother tongue. A small ethnic group of around 1,113 people (2010 census), they have spoken their own language for centuries, but because it’s not written and mostly limited to family communication, the language is increasingly being replaced by Russian.

If it’s natural for languages to die out, why not just let them? Firstly, indigenous languages support the identity of ethnic groups and help present unique cultural heritage and centuries-old ways of thinking. When an ethnic group loses its language, it loses a huge part of its identity.

Secondly, the more languages that exist in our world, the richer it is says Andrey Kibrik, director of the Institute of Linguistics of the RAS. “When the picture is colorful, it’s more valuable. But when everything is more of less the same, monotonous, the world becomes poor,” he argues (link in Russian).

2019 may have been proclaimed the International Year of Indigenous Languages by the UN, and Russia has been holding events to raise public awareness, but there is no specific recipe to reverse the situation.

The key objective in this respect, according to linguists and enthusiasts, is to make sure that indigenous peoples consider their language an asset rather than a liability. For that, a complex set of measures is necessary.

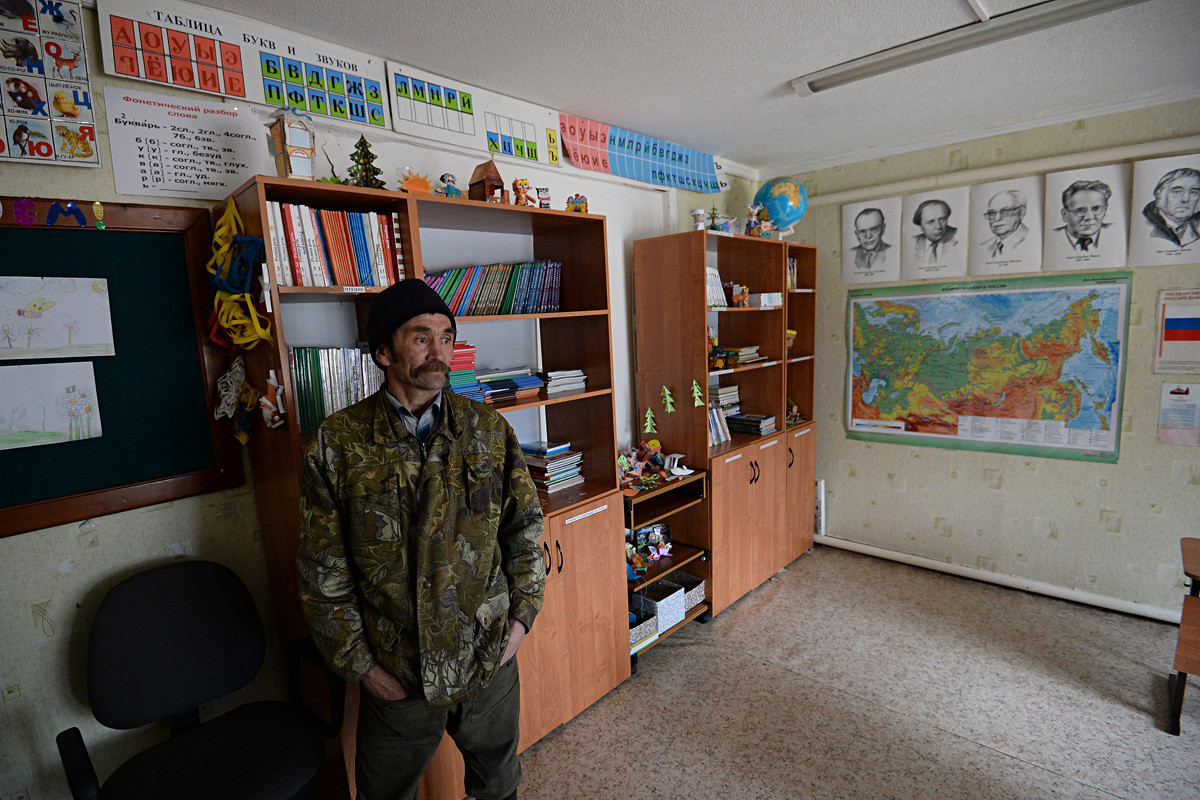

Khanty Roman Tylchin in a classroom of a public school that teaches three students, in the camping ground of Ust-Vatyegan belonging to Khanty indigenous people, in Nizhnevartovsk district of Khanty-Mansi Okrug.

Ramil Sitdikov/SputnikOver the last few years, the authorities have made more effort to recognize and protect minority languages by introducing a national program and establishing the Fund for Preservation and Research of Russia's Native Languages to support in indigenous languages. The fund is currently working on a new concept for learning and teaching minor languages, a system that the country doesn’t yet have.

Russia has also started to implement the “language nest” approach that originated in New Zealand, where older speakers of the language take part in early-childhood education with a view to improving intergenerational language transference. Since 2013, this immersion approach has been implemented (link in Russian) in five kindergartens in Russia’s Yugra regions and has produced positive results in teaching kids the Khanty and Mansi languages. In 2018, 139 kids took part in the program.

But enthusiasts argue that more needs to be done. Vasily Kharitonov, co-founder of Strana Yazykov (A Country of Languages), a non-profit project focused on promoting and creating a database for Russia’s indigenous languages, says organizing events where minority speakers can unite is helpful, so too online activities to encourage the preservation of languages. Kharitonov has created a website to promote the Nanai language, which only has around 50 native speakers left, all over 50 years old.

“I think our generation is responsible for transferring our languages and knowledge to the next. We shouldn’t just stand there and do nothing. We should fight,” Mutalov says.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox