One shouldn't idealize Soviet childhood and how children grew up in the USSR. After all, there were many dark sides and dubious rules. Take the most notorious one: "If you can't do it - we'll teach you; if you don't want to - we'll force you."

Many principles of Soviet education were established in the 1930s by legendary educator Anton Makarenko. At the time Russia had a huge number of street children who were liable subsequently to turn to crime; the authorities took them off the streets and placed them in orphanages, but it was already quite difficult to turn them into normal children. In one such colony for juvenile delinquents, Makarenko successfully re-educated street children into full members of society, relying on universal human values and high moral standards.

Much of his experience was included in Soviet pedagogical textbooks and successfully applied in the general education system. Here are some of his principles.

A lot of attention was devoted to a child's routine from a very early age. It was believed that everything - including sleeping and feeding - should take place according to a strict timetable.

'Follow a routine: Daily walks in the fresh air improve a child’s appetite, sleep and health. Moreover, the walks increase the quality and quantity of a mother’s milk'

K.S.MiturichIt was believed that even if a baby cries between feeding times, they shouldn't be "soothed" by breastfeeding. Soviet medical workers visited young mothers at home and carefully monitored how a child was gaining weight (in the USSR this, too, was supposed to be in accordance with set norms).

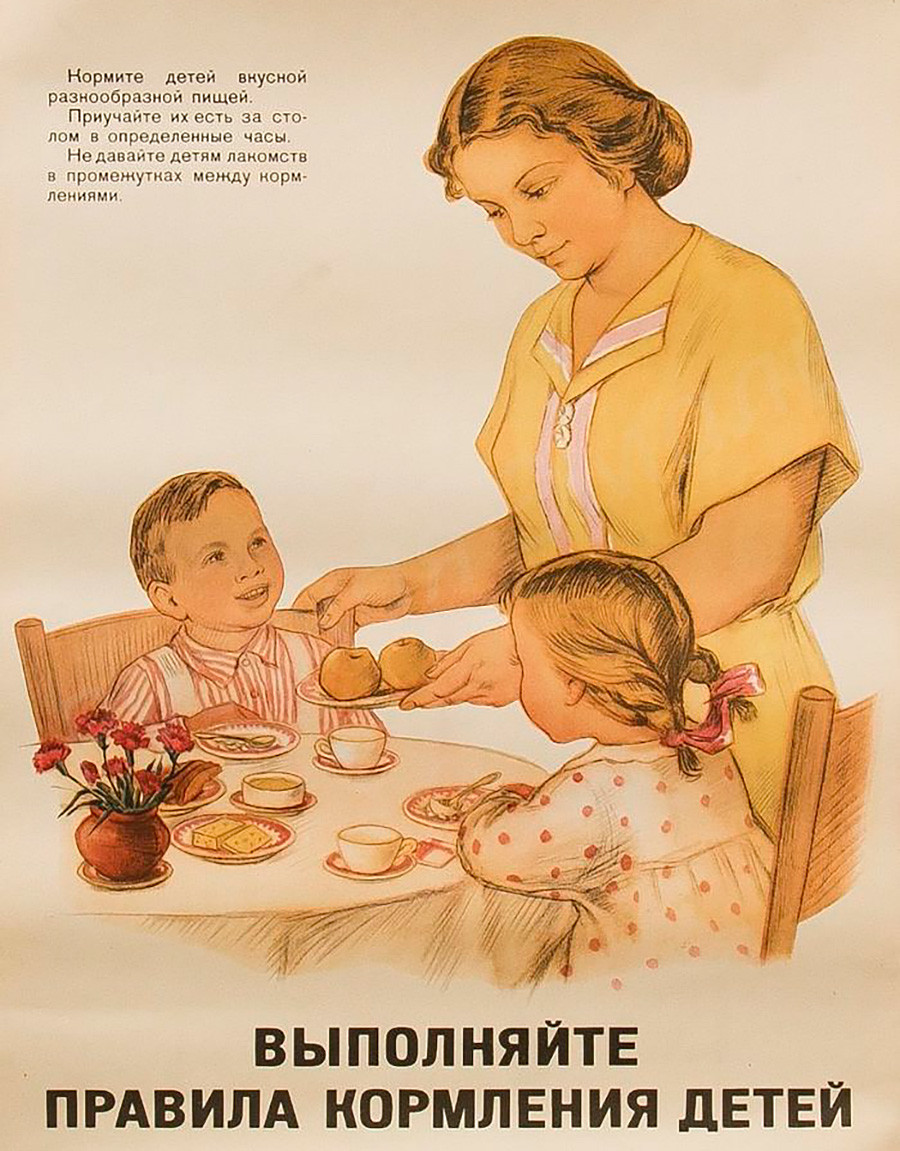

'Follow the rules of feeding kids: Give them tasty and varied food. Teach them to eat at the table at a set time. Don't give them sweets between meal time.'

K.S.MiturichDiscipline was also maintained with older children in these matters. Nurseries, kindergartens and schools always arranged meals at the same time and mothers were advised not to give children treats between meals.

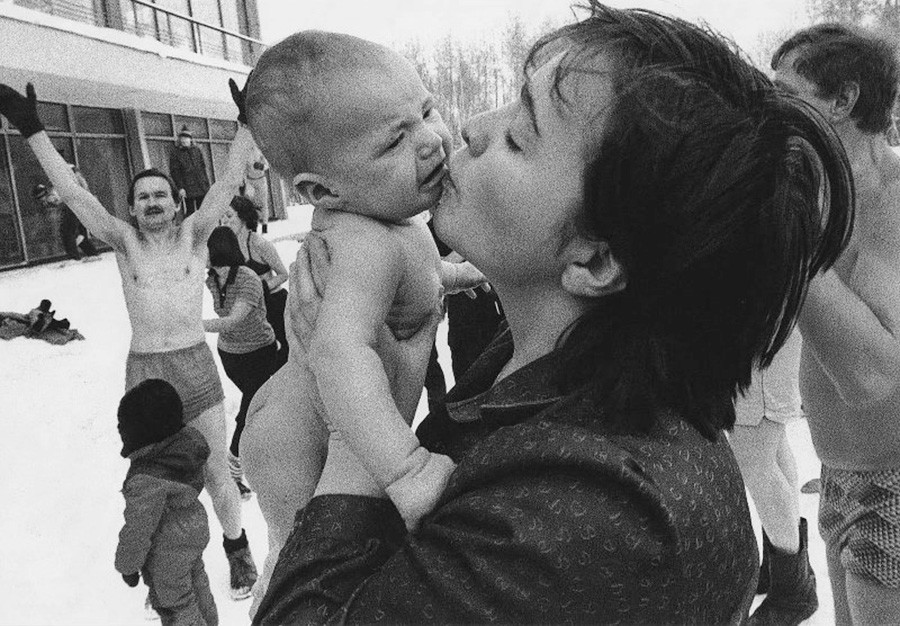

Fresh air was regarded as beneficial for babies' immune systems and good health, so fearless mothers would take their children in a pram for a walk for several hours even in freezing temperatures. Many children’s daytime sleep took place out of doors. (Read more about this here)

Naptime outside in the 1950s

Leonid Shokin/MAMM/MDFKindergartens also adhered to the same approach - children were put to sleep outside in order, among other things, to avoid outbreaks of various diseases.

'Healthy family,' 1985

Geogry Rozov/МАММ/MDFA special bit of fun was developing children's resistance to the cold by rubbing them with wet towels or pouring cold water on them out of doors. It was believed to be very beneficial for good health, including for the heart. And one of the main slogans in the USSR was "Sound mind in a sound body".

'Be physically active!'

M. NesterovaSchools had compulsory sports activities; furthermore, they varied according to the time of year: In winter children were taken outdoors for cross-country skiing and in summer running in the open air. At other times of the year activities were held indoors - children did running and athletics, and played team sports.

To encourage both children and grown-ups to do sports, even the most popular singer-songwriter, Vladimir Vysotsky, wrote a short comic song about the importance of morning exercises.

Children were sent to kindergarten from a very early age (even nursing infants) since mothers had to return to work as soon as possible for the benefit of the Soviet state. Also, socialization was an important skill that a child received at kindergarten. Children were supposed to learn to live and work in a team, as well as taking responsibility for their team.

Collective responsibility was an excellent technique that could be very helpful in dealing with today's bullying in schools.

'Respect the labor of others, clean up after yourself'

Archive photoIn the 1970s American academic and child psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner made a detailed study of the rearing of children in the Soviet Union and published a book, Two Worlds of Childhood: U.S. and USSR. In it he quotes a Soviet school teacher who explains how she deals with bad behavior in class.

"Let's imagine that 10 year-old Vova is pulling Anya's plait. I reprimand him once, then a second time, and a third - but he ignores me. Then I ask the class to note Vova's behavior. Now I can rest assured that during the break members of the Young Pioneer group who are on duty will have a chat with the boy. They will remind him that his misbehavior will affect the conduct marks awarded to the whole Young Pioneer group."

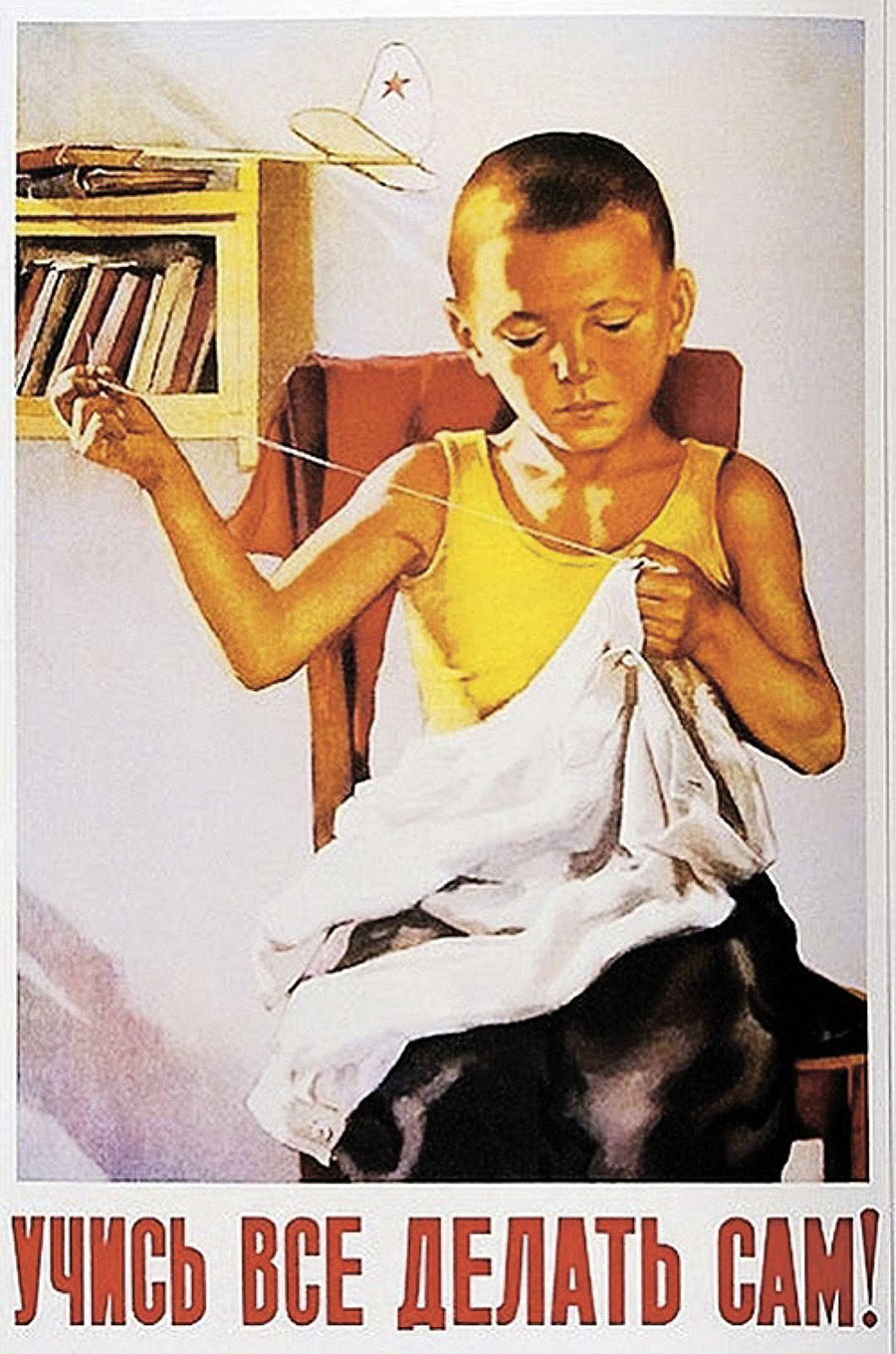

Notwithstanding collective responsibility, children had, of course, to take responsibility for themselves. In addition, from childhood they were gradually prepared for adult life. Without fail, they were expected to help adults and parents, and thus learn to do everything around the house, including cooking and simple manual jobs.

'We can do everything on our own, we help our mom'

Archive photo"At some point from Fifth Grade my duty was to tidy up the flat at weekends and to do the shopping. I always did it and knew no better. My twin sister at that time cooked dinner for the whole family while our parents were either at work or relaxed," 62-year-old Muscovite Sergei says, reminiscing about his childhood.

'Learn how to do everything by yourself'

Archive photoThere was a separate subject at school called "Work". Girls and boys were taught different things: Girls learned how to sew and cook, and boys how to hammer in nails, plane and saw wood, solder and even perform some simple electrical jobs.

Soviet children always had to be busy. And it turned out that the more things they had to do, the more they managed. Thus they were prepared for working and pursuing an active social life in a Communist Party cell, for example.

'Studies and relaxation, games and work - everything for the kids. Moms are happy and thankful for the extended school day.'

Archive photoEvery child either stayed at school after classes to study in an after-school homework club - it was called "extended day" (shortened to "prodlyenka") - or attended some other club. There were lots of children’s arts centers, sports clubs and music schools. Many children attended several clubs. Apart from the development of the child, they also made parents' lives much easier - they didn't have to worry about what their offspring were up to when they were at work.

Parents sought to give their children the best and what they themselves may have been deprived of during their own childhood. So they spent just about all their money on their children's education and development. Children were incentivized to take part in olympiads and competitions.

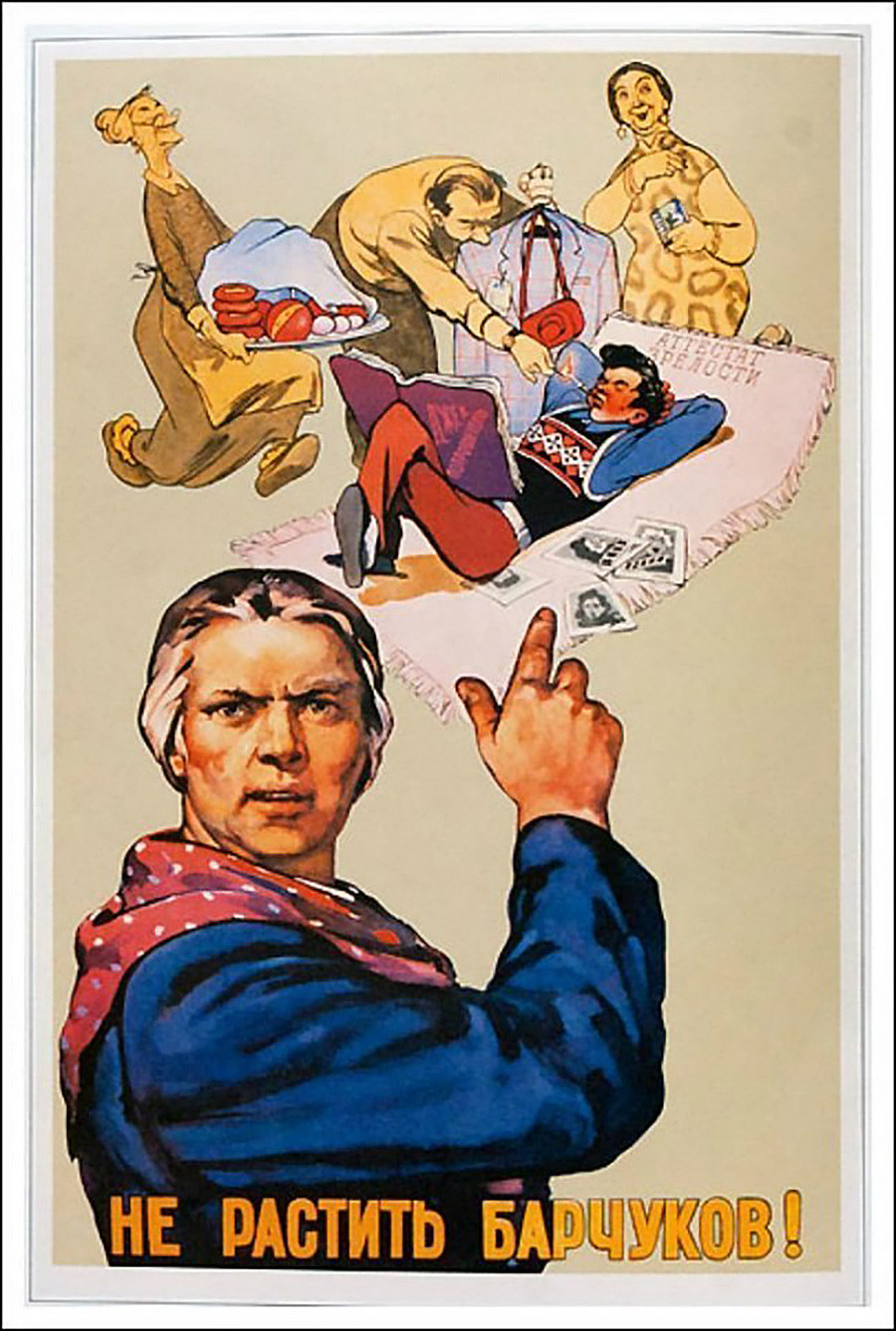

'Don't raise spoiled brats'

Archive photoIt was particularly strongly recommended that parents should not spoil their children, otherwise they would grow up to be like the lazy sons of the former nobility. Therefore, unlike today, Soviet children never had such a huge number of toys, or such a selection of clothes, or any luxury items (true, the shortage of goods was a contributing factor). From an early age Soviet people were supposed to be undemanding in their everyday lives.

It was believed that spoilt and pampered children would definitely turn into antisocial members of society, if not actual criminals!

Young naturalists, 1930s

Mikhail Grachev/MAMM/MDFSoviet children, as you must have realized by now, spent a lot of time outdoors. Many clubs also held their activities outside, an interest in botany and zoology was popular, and there were whole associations of young naturalists who studied the particular characteristics of the environment in their area. Children were also taken for hikes in the woods, and taught mountain climbing and kayaking.

Parents, too, would often take their children to the countryside - they taught them fishing and mushroom picking (most importantly, how to tell which varieties were edible).

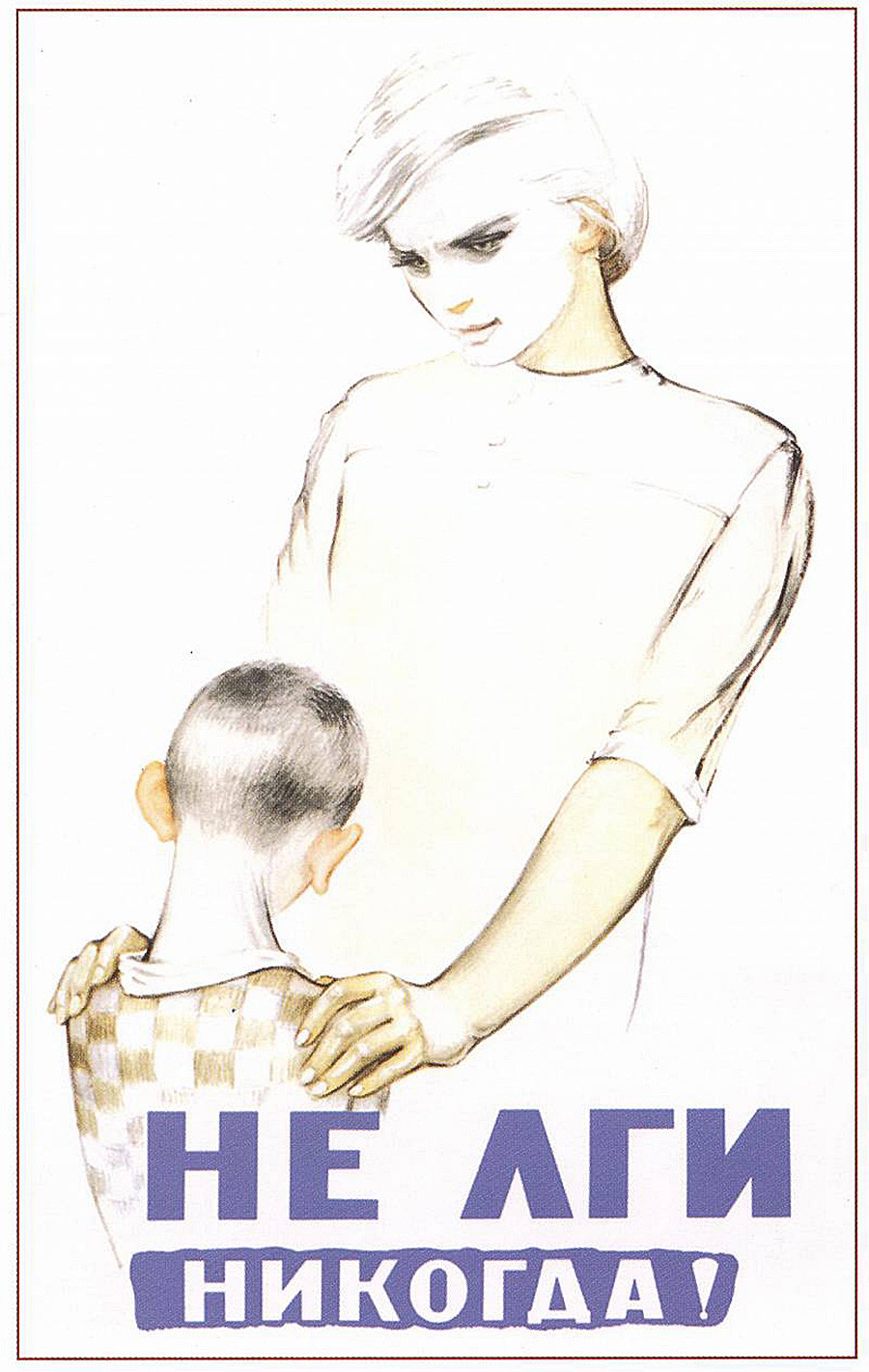

'Never lie'

Archive photoA lot of attention was devoted to ethical education in general. The famous poet Vladimir Mayakovsky wrote What is Good and What is Bad, which became a very popular poem. In the absence of religion, children were taught the rules of behavior not from the Bible but through the prism of the moral values of the Soviet people, the builders of communism. Anyway, there was little difference between them and the Ten Commandments.

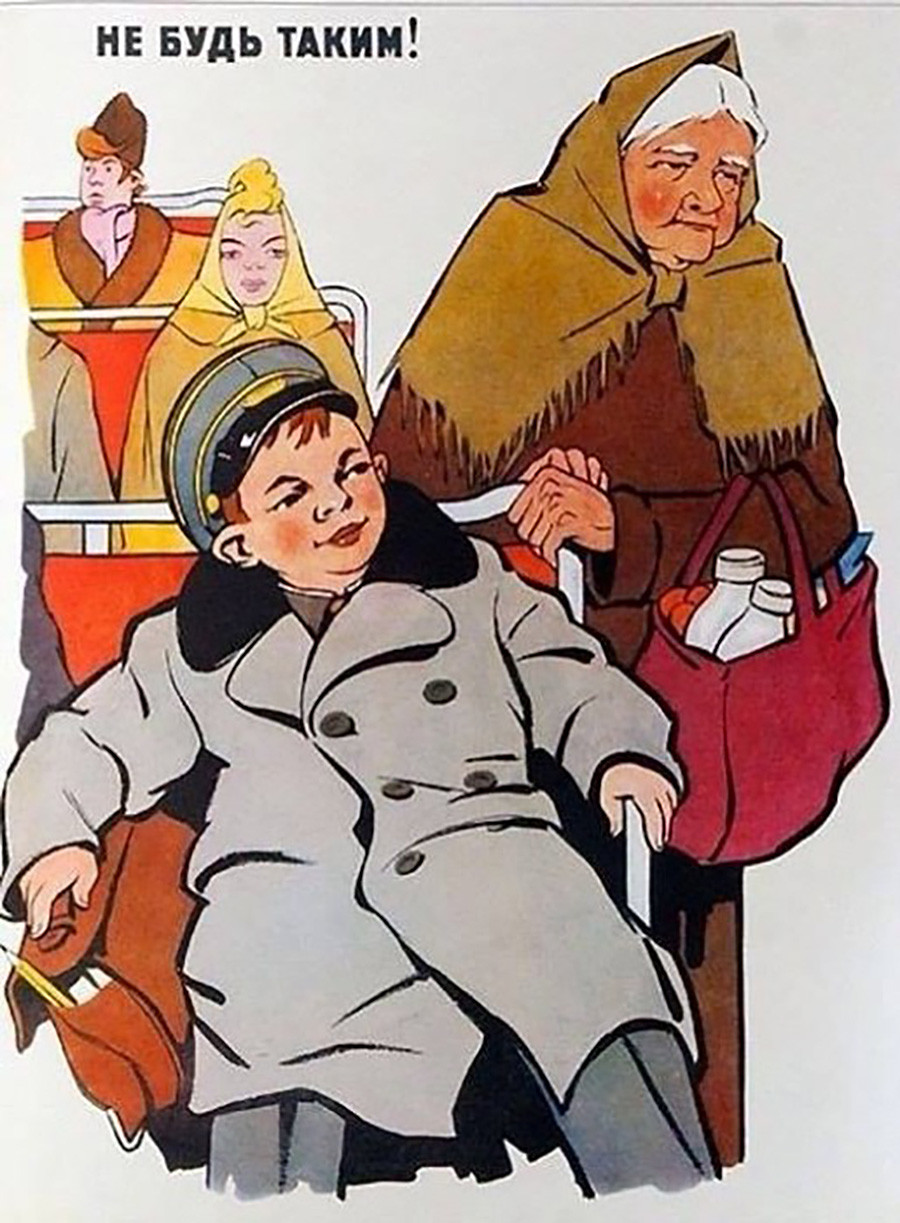

'Don't be like this!'

Archive photoIt was very important to live not for oneself but for others, not to seek personal gain and enrichment, not to tell lies, to observe cleanliness, and to respect one's elders: To offer them your seat on public transport and to help elderly people to cross the road or carry heavy bags.

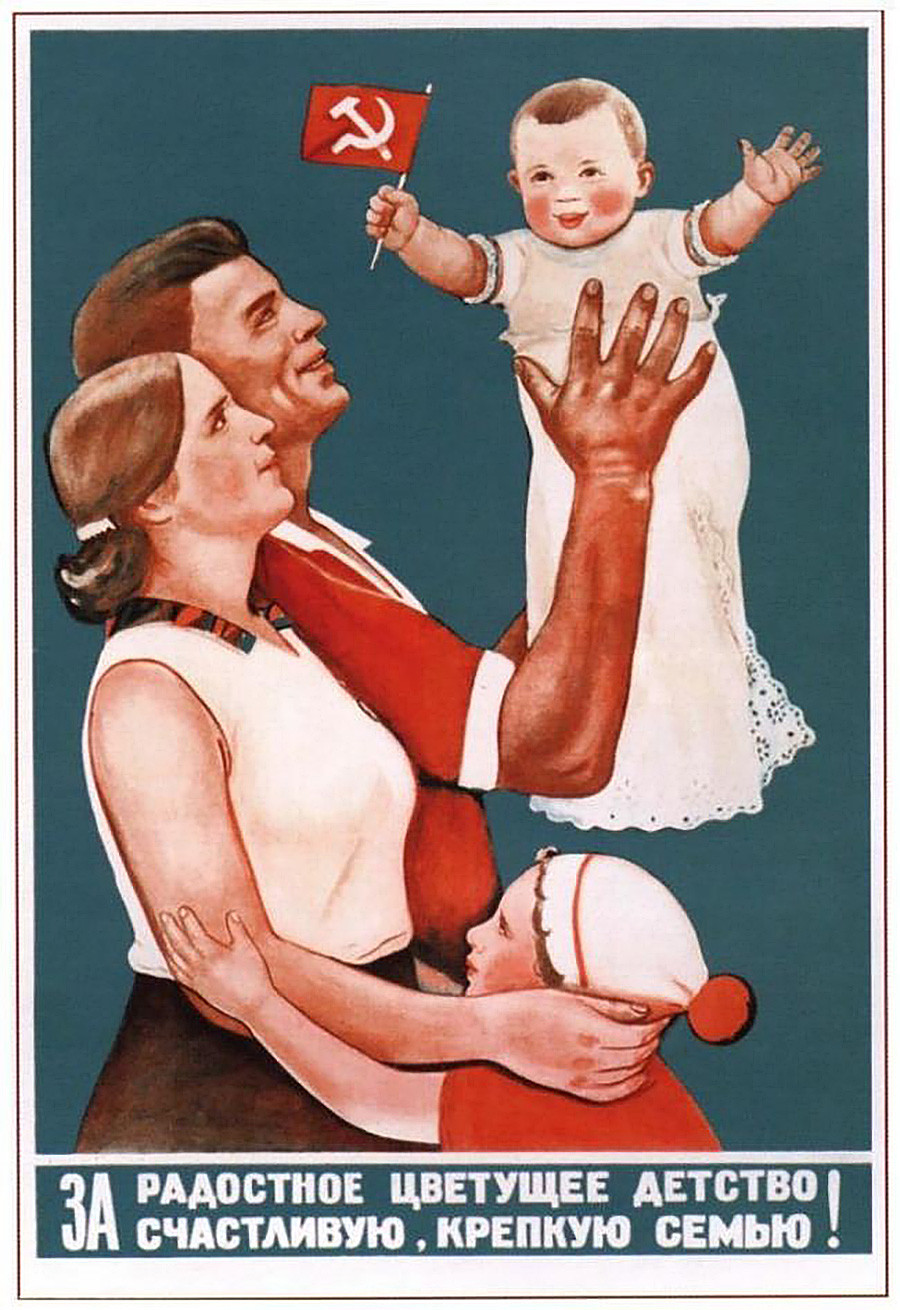

One of the most important values instilled in children was family, since family was an essential building block of Soviet society.

'For a joyful, blossoming childhood! For a happy, strong family!'

Archive photoThat is why from childhood girls were trained to become mothers and do the housekeeping (at the same time, they were never told that it was their only duty - girls were also encouraged to have professional skills). For their part, boys were taught to do "man's work", more physically demanding. It was very important to have served in the army.

"We simply laughed at those who had not served in the army. And even the girls didn't want to go out with them," says Ivan, 75.

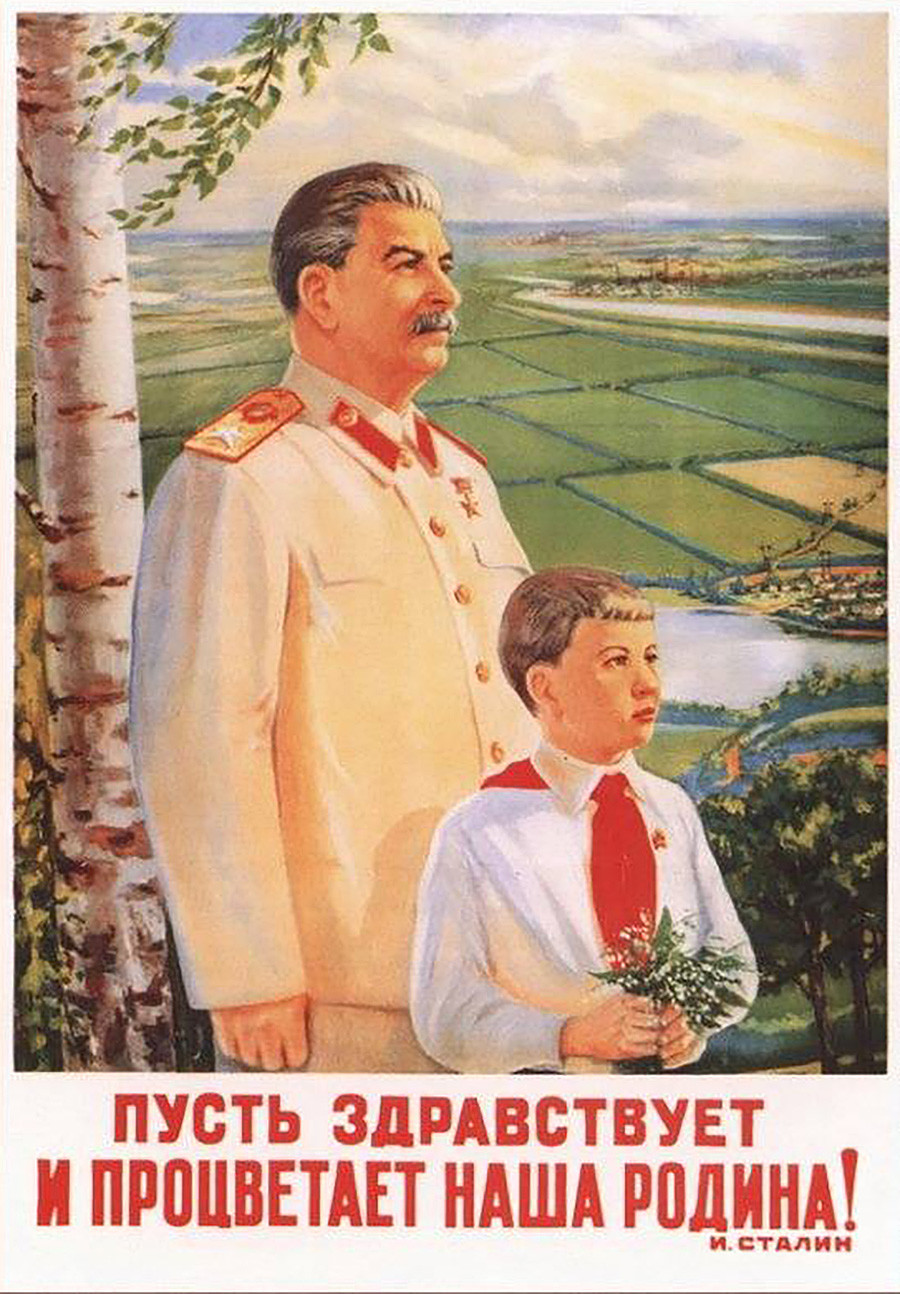

'Long live and prosper our Motherland!'

Archive photoAnd, of course, the main value instilled in Soviet children (as well as adults) was loyalty and love for the Motherland. For that, it was necessary to know its history, culture, geography and the USSR's great role in liberating the proletariat of the whole world from the oppression of capitalists.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox