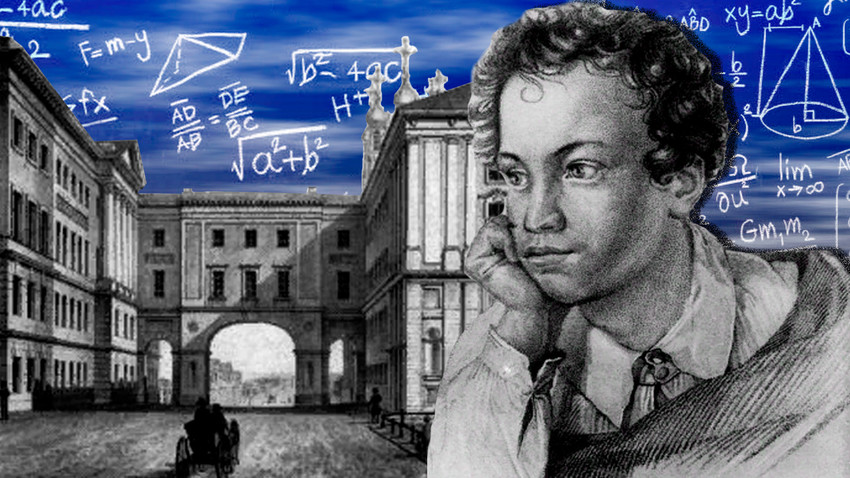

The future author of ‘Eugene Onegin’ was a mediocre student. He went to the Imperial Lyceum in Tsarskoe Selo, near St. Petersburg. Tsar Alexander I founded the lyceum in 1811 for children from the nation’s most prominent families.

Portrait of Alexander Pushkin, by Orest Kiprensky.

The State Tretyakov GalleryApparently, Russia’s greatest poet was not a math person. Pushkin had an ‘F’ in math, while political economy and Latin bored him to death. Pushkin’s knowledge of divinity was also scant. He scored top grades only in two subjects - Russian poetry and French rhetoric. But, Pushkin didn’t give up. When it was time to graduate from school, Alexander pulled an all-nighter and passed his graduation exams. “I want to understand you, I study your obscure language,” the leading light of Russian poetry wrote in 1830.

Pushkin often mentioned the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum in his verses. In his famous poem ‘To my sister’, written in 1814, he compares the lyceum to a “monastery” and calls it “a secluded land”. His room is being described as “a gloomy dark cell”, while he himself is a “monk” or “a prisoner from the dungeon”. In his poem titled ‘Farewell’, written in 1817, Pushkin depicts his school years as the “years of imprisonment”, calling his legendary school “a shelter of solitude”.

READ MORE: 10 reasons why Pushkin is so great

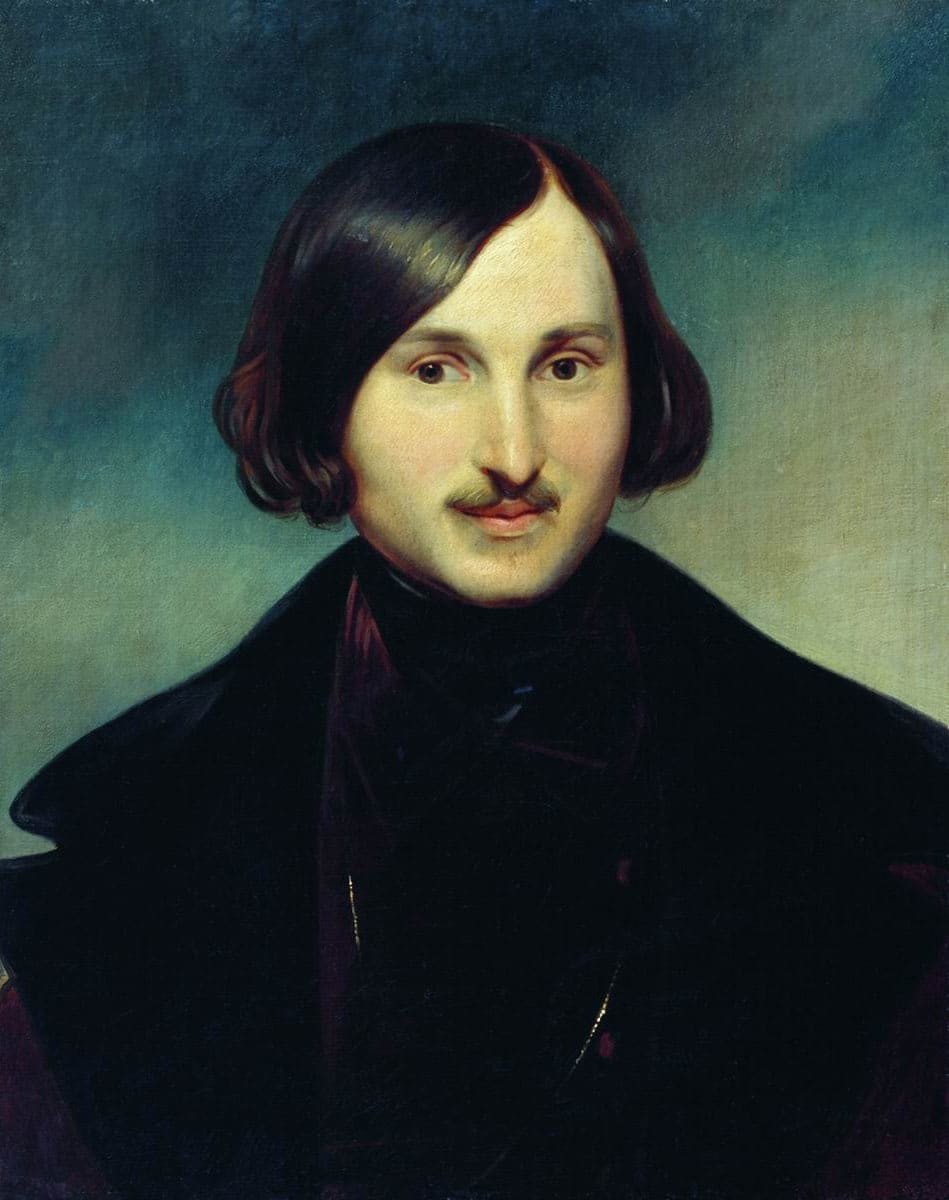

Gogol’s masterpiece ‘Dead Souls’ and his short story ‘The Overcoat’ have long been considered the marvels of Russian realism. However, his school years also hardly offered any promise of future success.

Portrait of Nikolai Gogol, by Otto Friedrich Theodor von Möller.

The State Tretyakov GalleryA novelist of preternatural genius, Gogol was born in Ukraine in 1809 into a landlord’s family. The boy first studied at the Poltava school, then part of the Russian Empire. Gogol was a creative person and enjoyed performing from an early age. Although he tried his hand at writing in different genres, Gogol had never dreamt of becoming a writer. He was determined to become a lawyer, instead. In 1821, the future author of the satirical story ‘The Nose’ entered the Gymnasium of Higher Sciences in the city of Nizhyn, 130 km away from Kiev.

According to his tutors and classmates’ recollections, thirteen-year-old Gogol behaved well around the school and in most lessons, but did not enjoy much success in his studies. Gogol had a passion for three things – drawing, literature and theater (he took part in almost every school play). Other than that, Nikolai had a reputation as a lazy student, who struggled with foreign languages.

“Least of all, one could expect from Gogol such fame as he enjoys in our literature,” his Latin teacher Ivan Kulzhinsky recalled. “He was a ‘terra ridus et inculta’ (an uncultivated and uncultivated soil). I can say without offense that when Gogol graduated from the gymnasium, he couldn’t conjugate a verb correctly in any language.”

Who would have guessed that the “lazy learner” would find his true calling as a consummate storyteller?

READ MORE: 5 must-read books by Nikolai Gogol to understand Russia

This legend of Russian literature spent his childhood in the southwestern city of Taganrog, where he attended a Greek school at the Church of St. Constantine and Helena. Chekov’s father had wanted his sons to become brokers.

Portrait of Anton Chekhov, by Osip Braz.

The State Tretyakov GalleryHowever, Anton had to repeat his school year twice. In the 3rd grade - because of poor grades in math and geography and then in the 5th grade – because he was repeatedly given ‘D’ and ‘F’ grades for Greek. Surprisingly enough, Chekhov never received anything better than a ‘B’ for his school literature lessons.

The school literally had a discipline to stick to. Anton’s teacher, Nikolai Vuchin, would beat his pupils with a ruler and lock them inside the classroom until evening.

In 1868, Anton Chekhov, together with his brothers Alexander and Nikolai, entered the Taganrog gymnasium. Alexander, the elder brother, studied diligently and was considered one of the best students. But Anton was rarely praised by his tutors. His teacher of the Law of God, Fyodor Pokrovsky, once told Chekhov’s mother: “Nothing will come of your children. Perhaps, only your elder son, Alexander, will prove himself worthy.”

At the gymnasium, Chekhov was famously poor at foreign languages, but he knew the Law of God perfectly well, and was even nicknamed ‘Pious Anton’. At school, there was even talk of him becoming a churchman. But when the future author of ‘The Cherry Orchard’ entered the medical university, he discovered himself in a completely new capacity – that of a skilled short-story writer.

READ MORE: 7 reasons why you have to read Chekhov right now

Akhmatova was born Anna Gorenko near the Black Sea port of Odessa, then part of the Russian Empire. When she was little, her family moved to the town of Tsarskoye Selo, close to St. Petersburg. “We had no books in the house, not a single book. Only a thick volume of [Nikolai] Nekrasov. Mom allowed me to read it on holidays,” Akhmatova recalled.

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin.

The State Russian MuseumShe studied at the Tsarskoye Selo girls’ gymnasium. “At first, I was doing bad, then much better, but I always studied with half a heart,” the author of ‘The Requiem’ recalled.

Anna studied in three gymnasiums: she began her studies in Tsarskoe Selo, then, after the divorce of her parents, spent a year in Yevpatoria, in Crimea, and graduated from the senior class at the Kiev Fundukleevskaya gymnasium, where her teachers were the future famous philosopher Gustav Shpet and mathematician Julius Kistyakovsky.

Akhmatova was more of a bookworm. She loved poetry since childhood and composed her first poem at the age of 11.

“At thirteen, I already knew [Charles] Baudelaire, [Paul] Verlaine and all the other damned French poets. I started writing verse early, but the funny thing was that when I haven’t yet written a single line, everyone around was sure that I would become a poet. Dad even teased me, calling me a decadent poetess.”

Akhmatova, often referred to as the leading Russian poet of the 20th century, spoke quietly and modestly about her accomplishments: “I was the most ordinary schoolgirl.”

READ MORE: What you need to know about legendary Russian poet Anna Akhmatova

The author of ‘The Poem of the End’ studied at several private schools. At the age of nine, Tsvetaeva entered a girls’ gymnasium in Moscow, but shortly after, left for Europe with her family. Her mother was diagnosed with tuberculosis and needed urgent treatment. Tsvetaeva continued her studies in German and French boarding schools.

Portrait of Marina Tsvetaeva, by Magda Nakhman.

In 1906, after the death of her mother, Tsvetaeva returned to Moscow and entered another private girls’ gymnasium. Marina enrolled in grade four, although she was the same age as the 6th graders. According to her school friend Sofya Leperovskaya, she was a “very lively, expansive girl with inquiring gray eyes and a mocking smile… She looked at everyone insolently, defiantly, not only at older students, but also at the teachers and tutors.”

Marina was never a teacher’s pet. “Staying in one gymnasium for a long time seemed boring to her and she behaved in such a way that the teachers tried to get rid of her and rushed to send her to another educational institution,” Leperovskaya recalled.

Tsvetaeva achieved ‘A’ grades without much effort. She “learned on the fly, but did not want to make an effort to master the skills of the exact sciences”.

READ MORE: 5 intriguing facts about great poet Marina Tsvetaeva that you can’t find on Wikipedia!

Tsvetaeva brought forbidden books to school to share with her schoolmates, including books by the father of Russian socialism, Alexander Herzen. “Marina was a rebel. School authorities were afraid of her influence on fellow students, since everyone considered her to be outstanding,” her classmate Irina Lyakhova said.

One day, Tsvetaeva was summoned to the principal and asked to change her behavior. “The leopard cannot change his spots!” she replied. “If you want to expel me, go ahead. I will enroll in a new gymnasium. I already got used to being a nomad. It’s even interesting.” A true original, Tsvetaeva was expelled for free-thinking twice.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox