The Russian language was subject to two large-scale reforms throughout its history. The first reform was carried out in the 18th century by Peter the Great, who replaced the Old Church Slavonic writing with a new, secular alphabet. The second reform was done by the Bolsheviks in 1917. Even though some reformers thought about switching to the Latin alphabet in both cases, this still didn’t happen.

Media exhibition in St. Petersburg, 1910.

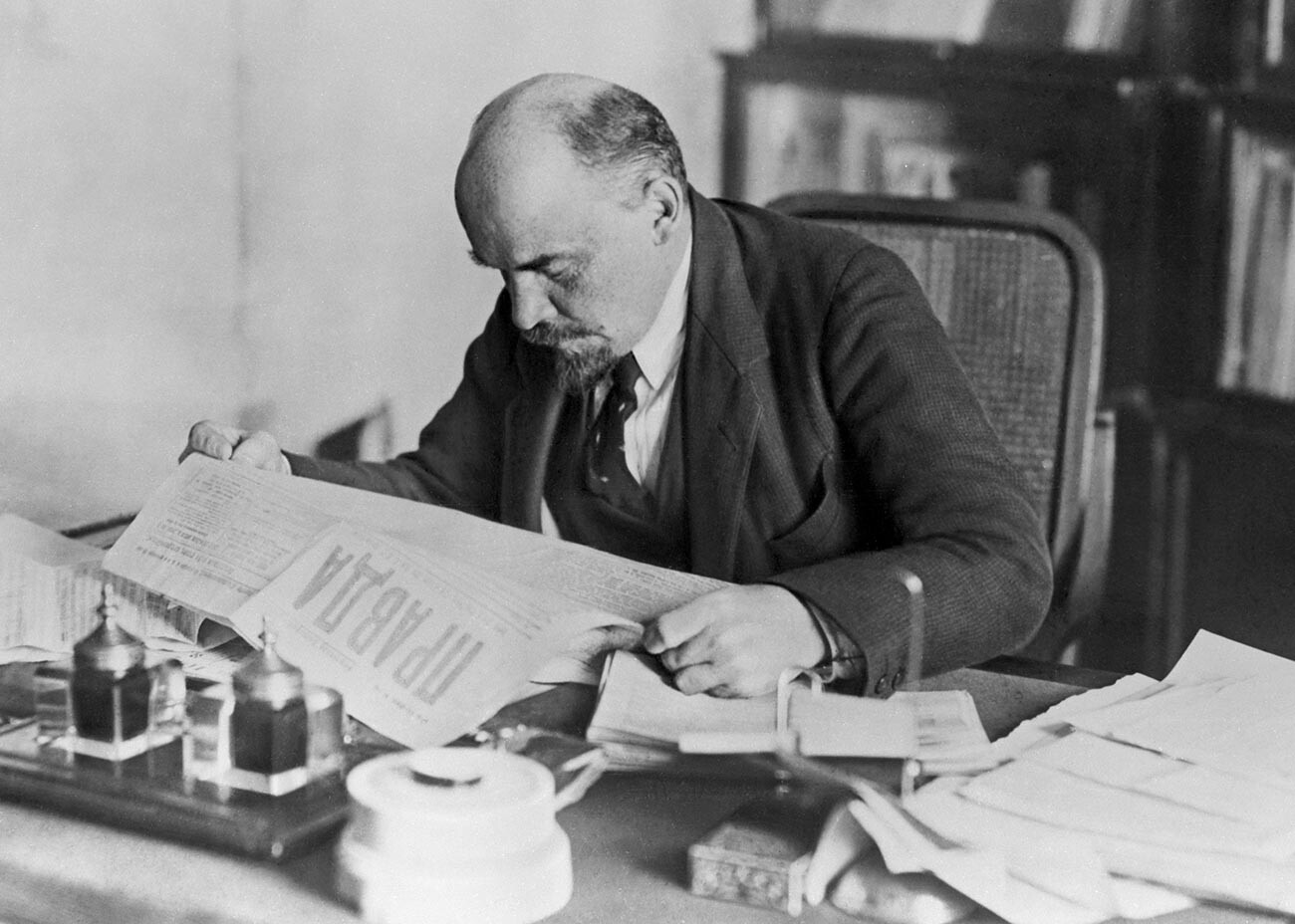

Central State Archive of Film and Photo Documents in St. Petersburg/russiainphoto.ruThe Latinization of the Russian language had a high priority after the October Revolution of 1917. After all, the plan to switch to a new alphabet fitted in well with the ambition of Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky to create and roll-out a new universal proletarian culture during the upcoming world revolution. According to Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar of Education of the USSR, using the Latin alphabet would make studying the Russian language easier for “proletarians of all countries”: “The need, or awareness of the need, to alleviate the preposterous pre-revolutionary alphabet, which is burdened with all sorts of historical vestiges, arose among all more or less cultured people.”

Lenin in his study in the Kremlin, 1918.

Petr Otsup/SputnikAlthough Lenin agreed with Lunacharsky, he was in no hurry to switch to the Latin alphabet: “If we will rush the implementation of a new alphabet or at once introduce Latin writing, which will certainly have to be adapted to ours, we will place ourselves in a position from where we can easily make mistakes, which will, in turn, be criticized by speaking of it as barbarism and such. I don’t doubt that there will be a time for the Latinization of the Russian language, but to act hastily now will be imprudent,” Lenin replied in his personal correspondence with Lunacharsky.

Nonetheless, a major reform of the Russian language did take place by the People’s Commissariat of Education under Lunacharsky. The pre-revolutionary Russian alphabet was cleared of a number of “unnecessary” letters. It is important to note that, for their language reform, the Bolsheviks used projects that were developed under Nicholas II at the Imperial Academy of Sciences in 1904, 1912 and 1917.

However, communist leaders and their loyal linguists did not abandon the idea of Latinization.

Kazan Kremlin.

Frank Whitson FetterThe Soviets sought to attract as many supporters as possible in the center and at the local level and, therefore, tried by all means to show all the peoples of USSR that they were willing to give them maximum freedom, up to the choice of which letters to write in their native language. The Russian alphabet was said to be poorly adapted “to the movements of the eyes and hands of the modern human” and was declared to be “a relic of the class system of the 18th and 19th centuries of the Russian feudal landlords and the bourgeoisie” and was also said to be “the display of autocratic oppression, missionary propaganda and Great Russian national chauvinism”. It was planned to first rid the Orthodox non-Slavic people of the former empire, who already had a written tradition in Cyrillic (for example Komi and Karelians), of the Russian alphabet - “a conductor of Russification and national oppression” by “tsarism” and the Christian Orthodox religion: “The transition to the Latin alphabet will finally free the working masses from any influence of the national bourgeois class, as well as religious influences of any pre-revolutionary printed books,” was said during a meeting of one of the commissions for Latinization. At the same time, the authorities planned to realize a transition to Latinization for all Muslims in the USSR who still used Arabic scripture. The intended goal herein was to eliminate “Quranic literacy”, as well as “the consequences of religious Islamic education”. Also, it was planned to include other languages that had their own authentic writing in the transition, such as Georgian, Armenian, Kalmyk, Buryat and others.

In the shortest possible time, unified Latin alphabets were created for dozens of illiterate (or poorly literate) peoples of the USSR, which were quickly and categorically introduced in the field – document publication, periodicals and book printing were transferred to new alphabets. By the beginning of the 1930s, the Latin alphabet had completely superseded Arabic writing among all the Muslim peoples of the USSR, as well as many Cyrillic alphabets of non-Slavic peoples and traditional forms of writing among the Mongolian population (Kalmyks and Buryats). The ending of illiteracy and the propagation of primary education among the population of the USSR in a short time frame can be considered positive results of the undertaken efforts. However, soon the situation changed rapidly and dramatically.

Craftsmen of the Communications School reading Stalin's book.

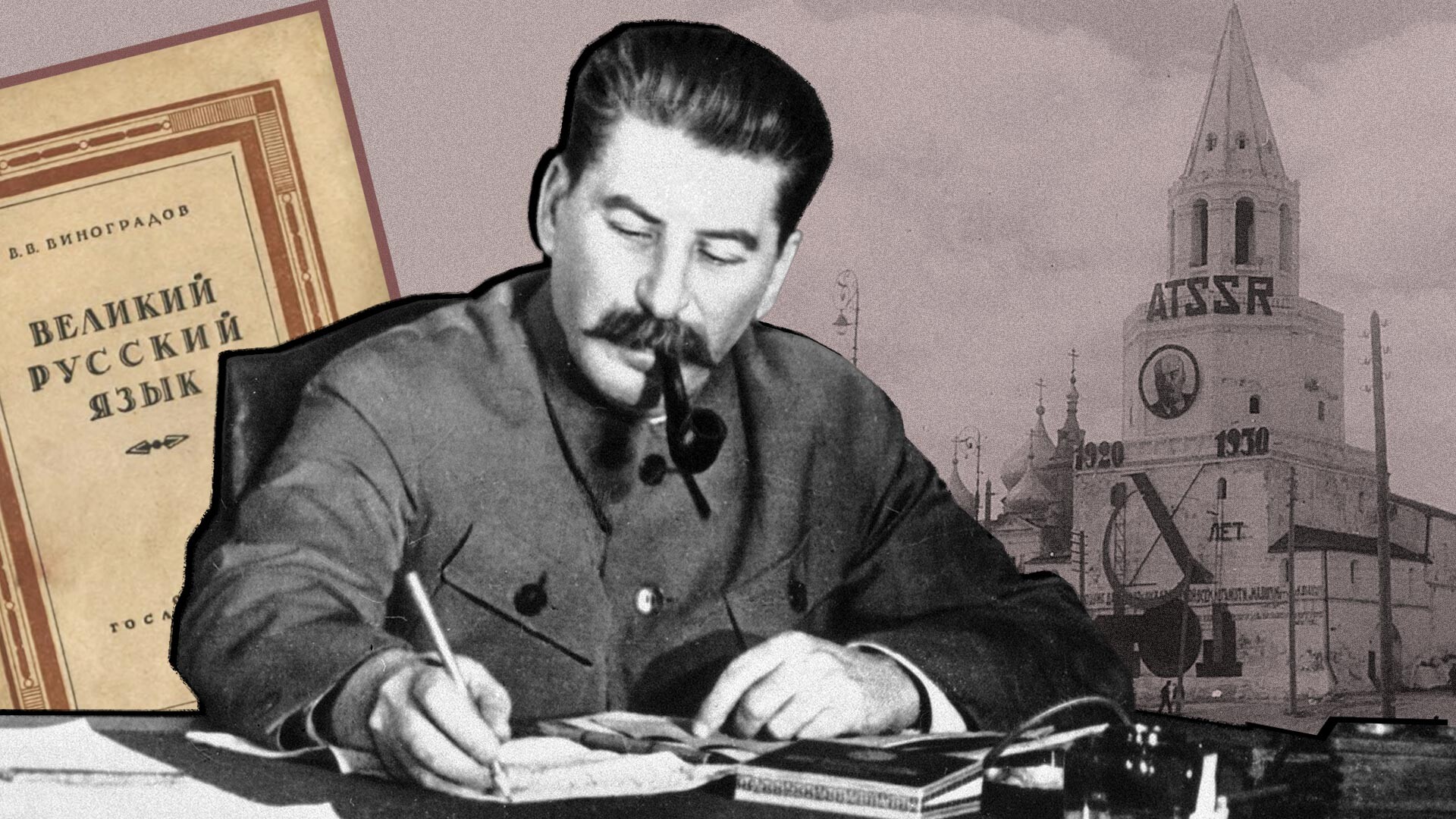

Yakov Khalip/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruWhile gaining influence in the communist party and gradually centralizing all political power to himself, Joseph Stalin formed his own vision on the development of the Soviet state. Stalin’s vision differed both from the views of the revolution’s leader Lenin, as well as his subsequent “left” opponents Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev. From the beginning of the 1930s, a partial revision of different phenomena, norms and social relations that were adopted in pre-revolutionary Russia gradually took place in the USSR. In time, many of the innovations that were brought by the revolution were declared “leftist deviations” and “Trotskyist bias”. Also, the global crisis at the time dictated its own needs. Therefore, the colossal costs for reprinting the old cultural heritage and ongoing reforms had to be cut.

Nikolai Yakovlev (1892-1974) - Russian linguist.

Archive photoIn January of 1930, the Commission for Latinization, led by professor Nikolai Yakovlev, prepared three final project drafts for the Latinization of the Russian language, which was considered “inevitable” during the time of Lunacharsky (1917-1929). However, the Politburo, led by Stalin, rejected the plans and forbade further expansion of energy and money on these projects. This decision came unexpectedly for many. In several public speeches in the following years, Stalin stressed the importance of learning the Russian language to further socialism building in the USSR. From 1936, the Latinized languages of the USSR were widely translated into Cyrillic with the goal of bringing the spoken languages of the peoples of the USSR closer to the Russian language. In turn, Latin alphabets were declared to be “out of touch with the times” and even “damaging”. The diverse linguistic autonomy that flourished in the early days of the USSR was quickly abolished, giving way to the Russian language, which was once again “restored in its rights”.

On March 13, 1938, a new resolution “on the compulsory study of the Russian language in the schools of national republics and regions” was issued by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks. According to this resolution, the Russian language was assigned the primary language in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and received official status in the union republics of the USSR. Representatives of the non-Russian Soviet intelligentsia, who resisted Cyrillization and the strengthening of the role of the Russian language, were subjected to repression.

Stalin.

SputnikThe exaltation of the Russian people and their language was only beginning to gain momentum under Stalin in the 1930s. During World War II, the importance of knowing the Russian language for all Soviet citizens became indisputable.

Viktor Vinogradov.

Oleg Makarov/SputnikAfter the end of the war in 1945, the famous book ‘The Great Russian Language’ was published by academician V. V. Vinogradov, in which the author writes the following to the tone of pre-revolutionary imperial publicists: “The greatness and power of the Russian language is universally recognized. This recognition has deeply entered the consciousness of all peoples, of all mankind.” In the late 1940s, the Russian language gained a new unprecedented position on the world stage, becoming one of the main spoken languages within the United Nations and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, as well as a compulsory language in schools and universities of all socialist countries.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox