"They have squandered the money they brought with them… They have incurred various debts… They have been excessively indulgent in their way of life and addicted to the female sex," the famous professor, Christian Wolff, wrote in his report about the conduct of the Russian students who arrived from St. Petersburg to study at the University of Marburg in Hesse. Among the students was none other than the future scientist and polymath Mikhail Lomonosov (1711-1765), a major figure in Russian science in the 18th century, after whom the country's leading university is now named. Here is the story of how Germany changed Lomonosov's life - not only professionally but also personally.

The son of a well-to-do peasant, Lomonosov was so hungry for knowledge that he secretly left his home in the village of Kholmogory near the city of Arkhangelsk in northern Russia and walked all the way to Moscow to enroll at the Slavic Greek Latin Academy. Joining a trade caravan, he walked the 1,168 kilometers during the Russian winter. Later, the future scientist moved to St. Petersburg where he studied at the university there that was under the auspices of the Academy of Sciences and started studying the German language, which was widely used in the Russian educational system because it was the native tongue of many academy members.

At the time, the Russian Empire needed specialists in mining and metallurgy to develop Siberia’s rich natural resources. The president of the Academy of Sciences, Johann Korff, offered to send several capable students to study in the Saxon city of Freiberg in Germany where the eminent physicist and mineralogist Johann Henckel taught.

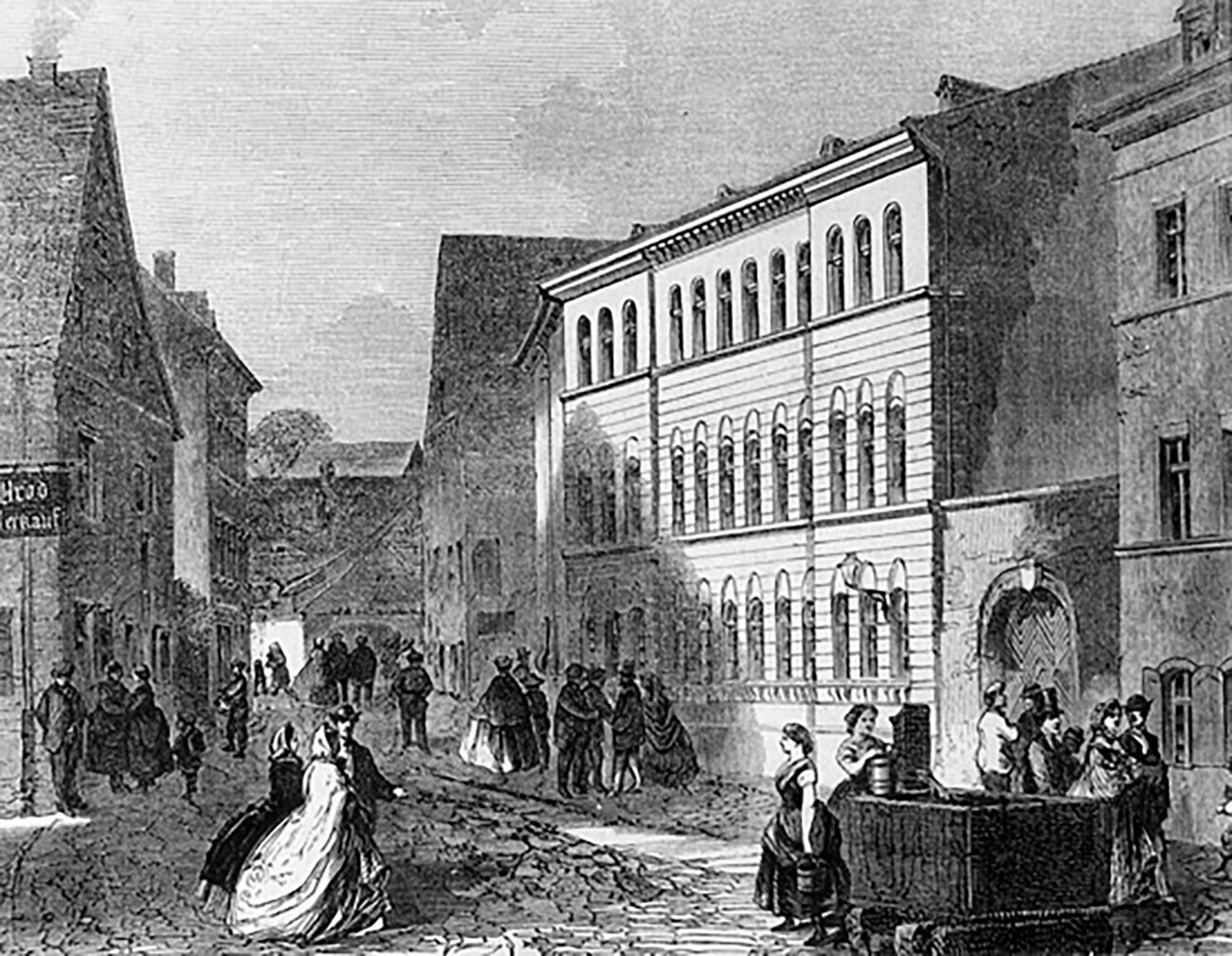

The foreign trip organized by Korff started in the university city of Marburg. Initially, the three selected students were to master the more fundamental sciences - mathematics, physics, philosophy and chemistry. Lomonosov and his fellow students were enrolled at the University of Marburg in November 1736.

Marburg University (late 18th century engraving)

Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera)The Russian students plunged headlong into the free-and-easy atmosphere of Marburg’s student life. Before his departure, Lomonosov received the very large sum of 300 rubles for the trip. He had lived frugally in St. Petersburg, so this money seemed to be a ticket to a life of luxury. He bought books and a new set of clothes, and hired a dancing teacher and fencing master. This provoked a reprimand from St. Petersburg: "No more paying for… dancing teachers or fencing masters. And, on a more general note, no wasting money on outfits and empty fopperies!"

Fencing classes, however, were virtually a necessity: According to Lomonosov, German students were "very pugnacious, and more often than not resort to their fists and, at times, to their swords". The Russians, however, were good at fighting back. Professor Christian Wolff, who looked after the young men at the University of Marburg, later confessed that the Russian students' departure was a relief because "no one dared say a single word to them as they kept everyone in a state of fear with their threats."

House in Marburg where Lomonosov lived

Christos Vittoratos (CC BY 2.5)Upon sending the young people to Germany, Johann Korff instructed them "to show good manners and behavior in all places during their stay, and do their best to advance their scholarly knowledge". While there was some doubt regarding the students' exemplary behavior, in his studies Lomonosov gave a splendid account of himself. Wolff quickly singled him out among the other students, describing Lomonosov as the "brightest mind among them."

"Since his arrival in Marburg, Mikhail Lomonosov, a young man of excellent abilities, has diligently attended my lectures on mathematics and philosophy and predominantly physics, and has tried particularly hard to acquire a thorough knowledge. I have no doubt whatsoever that if he continues his studies with the same diligence, he will in time, upon his return to his homeland, be able to be of benefit to his country, and this is something I wish for him from the bottom of my heart," the professor said in a report he wrote characterizing Lomonosov.

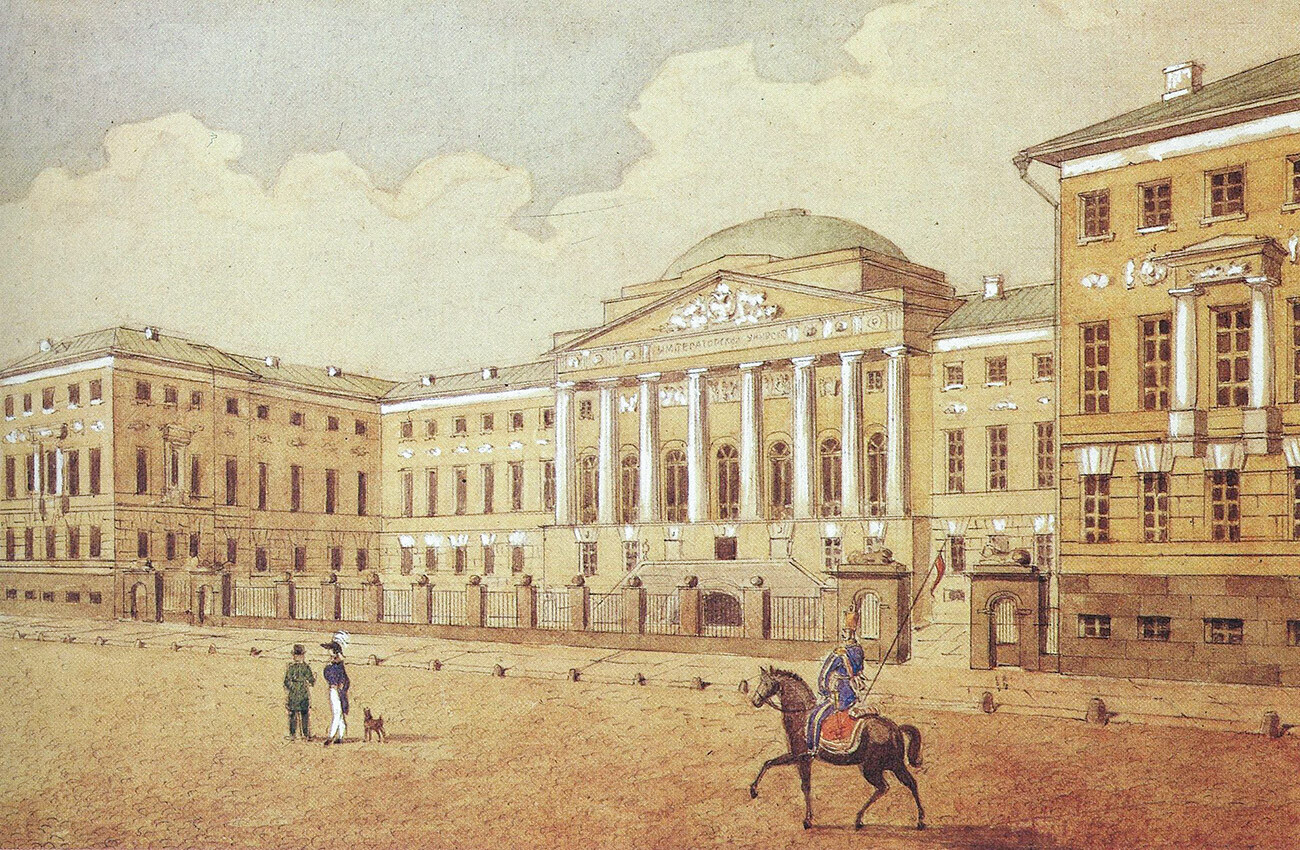

Wolff taught him that scientific thinking had to be the main quality of a true scientist, noted the Russian historian Sergei Pereverzentsev. Aside from knowledge, Lomonosov came away with many useful and practical ideas from lessons with the professor. Many years later, when he was drawing up plans for the founding of Moscow University, Lomonosov took into account Wolff’s ideas, specifically that he taught in German and not in Latin, as was the norm in those days. German, of course, was the students' native tongue, and so Lomonosov ordered that teaching at Moscow University be conducted in the students’ native Russian and not in Latin.

Portrait of German philosopher Christian Wolff

Johann Martin BernigerothWolff's lessons weren't confined exclusively to science: Some were lessons of life in a broader sense. For instance, after the Russian students completed their studies in Marburg, Wolff paid off their debts out of his own pocket (although the Academy later reimbursed his costs). This impressed Lomonosov very deeply - to such an extent that he "could not utter a word from emotion and tears". The professor had a good understanding of the students, their difficulties and needs, and thus adopted a friendly and indulgent attitude to his pupils despite their behavior. Lomonosov harbored an enormous sense of gratitude and appreciation towards his Marburg mentor for the rest of his life, and in his commentaries he described him as his "benefactor and teacher".

After completing their studies with Wolff, the students set off for Freiberg to study metallurgy. Their new teacher was Johann Henckel, the physicist and mineralogist who originally suggested to Academy of Sciences President Johann Korff the idea of sending the students abroad. Even before they arrived in Freiberg, Henckel received from Korff a rather unflattering character reference of his future pupils: "These three individuals are very unequal in terms of their diligence and achievements; but in their prodigality they seem to outdo one another."

Freiberg Mining Academy

Public domainIn spite of this, the teacher adopted a fairly amicable manner towards the new arrivals, and initially relations with Lomonosov developed fairly well: Under the professor's supervision he diligently studied the subject matter for which he had originally undertaken his many years of peregrinations.

With time, however, between Henckel and his pupil relations between the two started to fray. On becoming aware of the care-free and often wild lifestyles of the young men, the academy decided to cut their maintenance allowance and asked the professor "not to issue them with any ready cash apart from one thaler a month <...> as pocket money and for various incidental expenses, and <...> to let it be known everywhere in town that no one was to grant them credit, since <...> for the repayment of such debts the Academy of Sciences <...> will not refund a single farthing."

View of the house where Lomonosov lived in 1739-1740

Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera)Henckel adhered strictly to the instructions that he was given, and relations between him and Lomonosov grew increasingly strained. In their letters to St. Petersburg, both men painted each other in the darkest colors. Matters were brought to a head when Lomonosov quit Freiberg without permission, and then wandered around different towns for a while hoping for a meeting with a Russian diplomat in order to arrange his return home. That didn’t work out and finally he went back to Marburg.

Lomonosov already had some friends and connections in Marburg. Having first come here at the very start of his studies, in 1736 he had found lodgings with Frau Catharina Elisabeth Zilch, the widow of a prosperous brewer. Having lost her husband, she was forced to rent out rooms to take care of her children - a son Johannes and a daughter Elisabeth Christina. When the student from Russia first crossed the threshold of the Zilch household, Lischen was 16 - and Lomonosov almost 10 years older. A few years later, before the student's departure for Freiberg, the couple married and at the end of 1739 Elisabeth Christina gave birth to a daughter.

Elisabeth Christina Lomonosova (Zilch)

Public domainThe little girl was regarded as illegitimate since the marriage ceremony between the Russian student and the German girl – since they were from different religious denominations – had not been consecrated in church and was regarded as a civil marriage. But after Lomonosov's return, a church wedding finally took place. A Marburg church register entry reads: "On June 6, 1740, the marriage took place of Mikhail Lomonosov, kandidat in medicine, son of Vasily Lomonosov, a merchant of Arkhangelsk, and Elisabeth Christina Zilch, daughter of the late Henrich Zilch, a member of the town council and church warden."

Apart from his work in the exact sciences, the scientist was also deeply passionate about literature and writing verse. His first poetic effort dates to his time in Marburg, and some biographers link it to his feelings for Elisabeth Christina. It was a translation of an ode ascribed then to the ancient Greek lyrical poet Anacreon: "I wish to tell of the sons of Atreus, I wish to sing of Cadmus; but my lyre-strings sing only of Love."

Portrait of Mikhail Lomonosov

Leonty MiropolskyIt was difficult for Lomonosov to provide for his family with the meager stipend that he got from the academy. The scientist fell into debt once again and his creditors threatened him with time in debtors prison. To make matters worse, he was forced to conceal from St. Petersburg that he had taken a German wife.

Clearly the time had come to decide what to do next – to stay or to go home – and having thought long and hard about his situation, the student "saw himself compelled to leave the city, relying on charity to sustain him on the way <...> Saying farewell to no one, not even his wife, one evening he went out of the courtyard and set straight off on the road to Holland." His plans, however, were foiled by a fortuitous set of circumstances: In a village near Düsseldorf he drew the attention of a Prussian recruiting officer and his comrades.

"The officer courteously invited him to sit down next to him, have dinner with his soldiers and drink from a so-called ritual cup that was passed round the assembled company. After dinner, they impressed upon him what a great honor it was to serve in the Royal Prussian Army. Lomonosov had been wined and dined so heartily that he could not remember what happened that night. On waking, he saw he was wearing the red collar of the Prussian uniform. In his pockets he felt several Prussian coins. Calling him a brave soldier, the Prussian officer told him in the meantime that he would of course find fortune after starting service in the Prussian army. The officer's subordinates addressed him as brother… "

This is how the Russian scholar, who had become a Prussian cavalryman overnight, found himself at the fortress of Wesel, more than 170 km from Marburg, where new recruits from the district had been sent. Desertion was severely punished in the Prussian army, but Lomonosov was determined to escape.

One night, picking just the right moment when he guessed that the soldiers on guard had fallen asleep, the Russian student climbed out through a window, scrambled down the ramparts, swam across a moat and began to run, all the while pursued by Prussian servicemen. Eventually, the Russian fugitive managed to shake off his pursuers. After his aimless wanderings in a foreign land, Lomonosov again returned to Marburg where he wrote a contrite letter to St. Petersburg.

Moscow University's first building

Public domainFinally, in the summer of 1741, on his third attempt, the scholar returned home to the Russian Empire, having spent almost five years abroad. He left his pregnant wife in Marburg, continuing to keep her a secret. Only after two anxious and uncertain years did Elisabeth Christina travel to join her husband, having, through her own efforts, discovered the whereabouts of the scientist with the help of a Russian diplomat.

The diplomat helped her to send a letter to her husband. Upon reading the letter Lomonosov, according to his biography, exclaimed: "Good God! <...> Circumstances prevented me <...> not only from bringing her here, but also from writing to her. Now let her come; tomorrow I'll send 100 rubles for the journey." Thus the scientist's family was finally reunited, and the adventure-packed German period of Lomonosov's youth finally came to an end.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox