5 facts you probably didn’t know about the Russian alphabet

1. The modern version of our alphabet is only 81 years old

The Russian alphabet we know today has existed in its current form since 1942. It was then that the letter “ё” officially ceased to be a variation on “e”, albeit quickly becoming optional again, only really being mandatory at the official level.

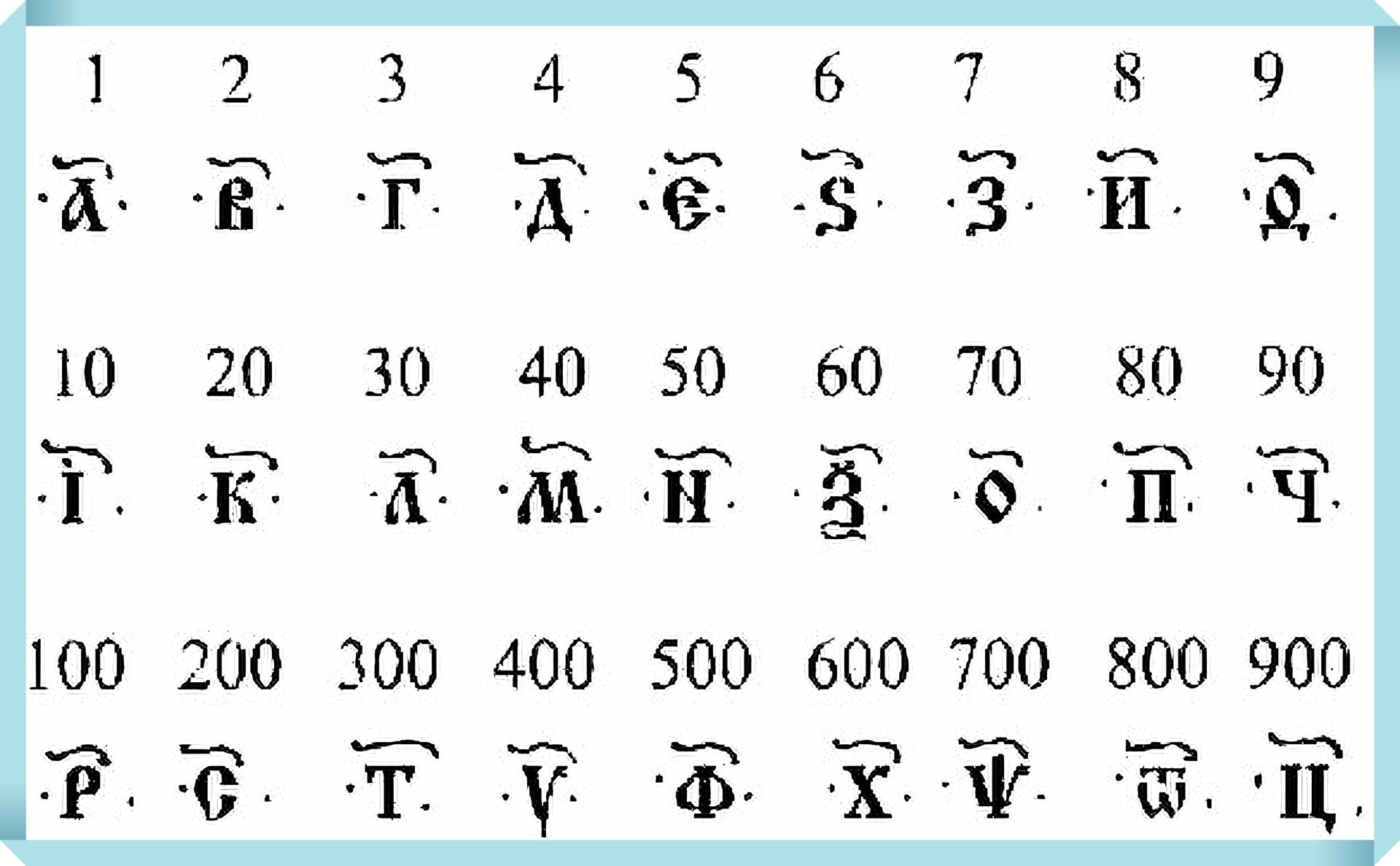

2. Numbers in the ancient Russian alphabet were depicted as letters

Prior to Peter the Great’s 18th century reforms, ancient-Russian letters were used not only for words, but numbers as well. One could only tell the two apart by the zig-zag sign over the letter, which signified that the letter was a number.

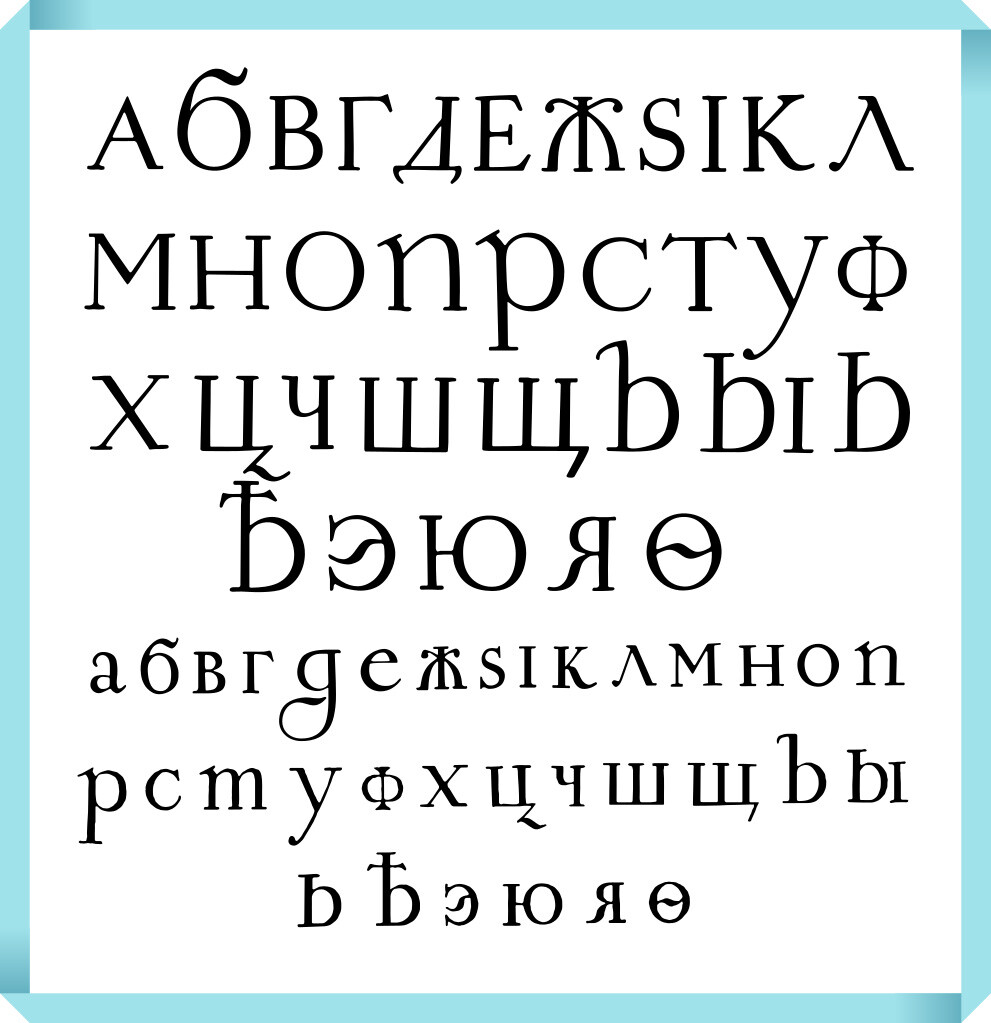

3. Peter the Great “dressed” the alphabet in European clothing

During the reign of Peter the Great, science and education were actively being advanced, which went along with the necessity for printing more books. And so, in 1708, the emperor enacted the first reform of the Russian alphabet by removing the unnecessary, decorative elements in the letters, bringing them closer in style to Latin, while some - “ksi”, “omega” and “psi” - were outright eliminated. That is how the “civilian” or “Amsterdam” writing appeared, intended for public and media use (the metal letters were cast in Amsterdam).

Public books transitioned, while Church writings stuck with the old ways. And that is how we got Arabic numerals.

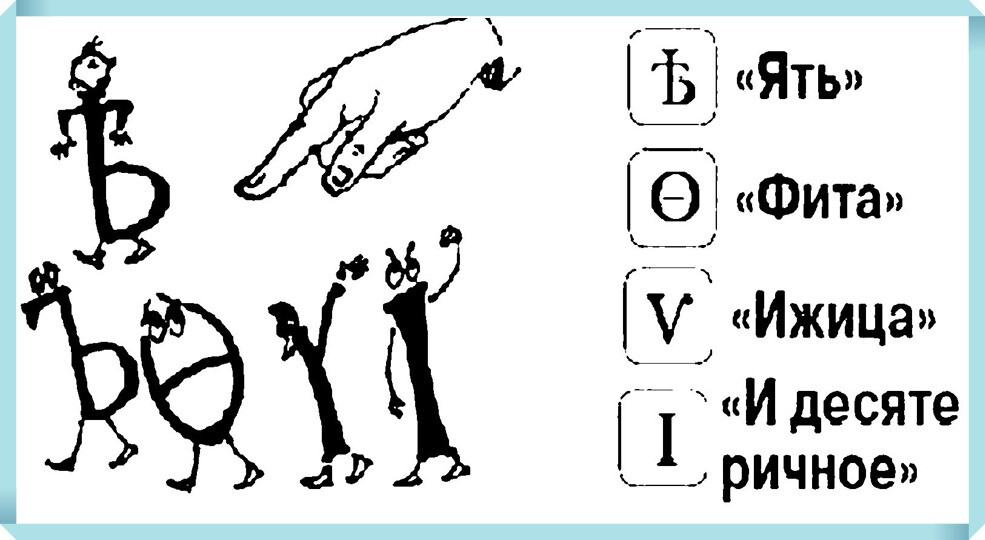

4. Bolsheviks made the largest contributions

The final major reform came in 1918. It was then that the letter “я” was made the last letter of the alphabet while “Ѳ” (fita), “Ѵ” (izhitsa) and “I” were thrown out.

The reforms were being readied since 1904, and affected not only the content of the alphabet. For instance, instead of “ять” (ѣ) in the words онѣ and однѣ, we got “И”: они, одни. The hard sign remained only as a separator and was no longer used at the end of words. Furthermore, the rule governing “З/С” prefixes came into being: “c” before plosive consonants, and “З” before fricatives.

5. Cyrillic almost became Latin

The idea to change Cyrillic writing into Latin was supported by the People’s Commissar for Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky: he believed the Russian alphabet to be a “relic of pre-revolutionary Russia”. In 1929, linguist Nikolai Yakovlev set about adapting Russian to Latin writing, as well as developing a separate alphabet for illiterate peoples of Russia and a Latin version of one for the Muslim nations. But, the idea was abandoned during Stalin, who actively supported the spread of the Russian language.