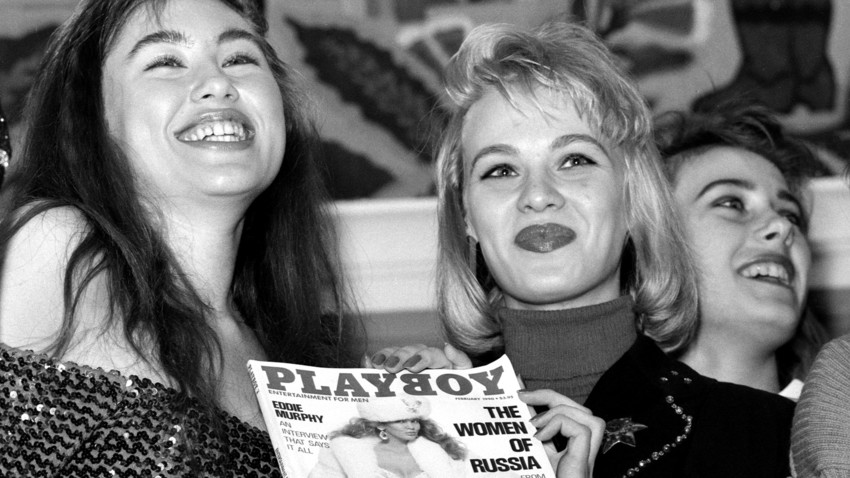

A Playboy magazine devoted to Russian women, 1990.

Valentin Kuzmin, Valery Khristoforov/TASSThe death of Playboy Magazine founder Hugh Hefner has prompted people around the world to debate his legacy and impact on show business. However, in

In the U.S. Hefner’s passing made

Some have praised his open attitude towards sex (once unthinkable in the Soviet Union) while others say he damaged the country’s moral values with the images published inside Playboy’s glossy pages. Despite a polarized public, everyone had heard of Playboy.

Like most foreign magazines, Playboy was unavailable in the USSR and only researchers and social scientists were able to obtain it through special permission in special library departments.

Nevertheless, the magazine’s name was often mentioned in satirical Soviet publications as an example of the “rotten Western lifestyle.” In 1972, the Soviet Education Ministry publication “Ideological Fight and Modern Culture” stated that Playboy turned into a successful magazine because it was able to “stimulate the feeling of lust among its readers.”

Interestingly enough, some Soviet critics did not mention Playboy by name but freely translated it into Russian as

Even during that time, the magazine had plenty of fans including prominent Soviet writer Vasiliy Aksenov, who got his hands on Playboy with the help of a friendly U.S. diplomat.

The late writer even stated in one of his books that he too was trying to find the Russian equivalent for Playboy - he came up with

However, dissident writer Aksenov - who spent almost 20 years in emigration - was not necessarily the target audience: Playboy had many admirers from a wide range of backgrounds.

Famous Soviet physicist Pyotr Kapitsa also found a way to subscribe to Playboy. But according to KGB records the magazine editions which were first mailed to Kapitsa’s friend in the U.S. were confiscated by the authorities after his friend tried to send them to Russia, together with a bunch of scientific papers.

The magazine was finally deemed acceptable during Mikhail Gorbachev’s reign. Famous chess player Garry Kasparov was the first Soviet citizen to give an interview to Playboy in 1990. A year before the chess champion offered his candid words, another citizen appeared on the front cover: Natalya Negoda. She was a star of the perestroika film era. Little Vera was one such film she starred in - it’s about a teen girl struggling with her parents in a remote Russian town.

Playboy officially came to Russia in 1995 but the country had already opened up to the West by then, and the magazine arrived a little too late to seriously stir a reaction.

Former editor in chief of Playboy Russia, Rem Petrov, is keen to stress that the publication offered more than naked flesh and blond girls.

“Playboy Russia managed to deliver exactly what the U.S. edition promised in its motto - entertainment for men. Smartly written, well designed and illustrated, it has opened up a new era of western-type men's magazines in Russia. Men's Health, GQ, Esquire - they all came later; Playboy was clearly a pioneer,” he told Russia Beyond.

Poet and literary critic Vladislav Vasukhin told Russia Beyond he thinks Playboy is more of an anecdote or a cliche than a magazine. He says people were keen to appear in the magazine due to the recognition is brought.

Ironically enough, some Russian Playboy readers jokingly called it “Novi Mir with sexual content”

However, in an interview with Republic magazine in 2010, Troitsky himself confessed that while he wanted the Russian Playboy to run quality stories, he resisted the standards set by Hefner. “I think it was a shame to shoot women with silicon boobs in Playboy. It was a policy guided by one man, Hugh Hefner, and I resisted it as well as I could. But it’s hard to fight Pamela Anderson,” he said.

While

Playboy gave Borisova the career boost she was dreaming of: “You’ll be sitting in your slippers with your wife on a cranky sofa while I will be a star,” she wrote angrily to her university boyfriend one year before her Playboy shoot. Perhaps Hefner would have loved to hear that.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox