Punching a hole in the Iron Curtain: How was an American tycoon able to make deals with the USSR?

Leonid Brezhnev and Armand Hammer talk during a meeting.

Vladimir Musaelyan/TASSIn a memoir written many years after meeting Vladimir Lenin in 1921, Armand Hammer recalled the Bolshevik leader’s charisma: “If he had ordered me to jump out of the window I’d have probably done so.” Sounds impressive, especially from someone who was a committed capitalist, always determined to make a fortune.

Nevertheless, Hammer knew how to look beyond ideological hostilities and make himself useful to both sides, enriching himself in the process. He followed this strategy for the 70 years of the USSR’s existence, working as a negotiator, businessman

Born into socialism

Though Hammer wasn’t a socialist, his father, Julius Hammer, a Jewish émigré from Odessa and a doctor and pharmacist, occupied a leading position in the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP). Moreover, the name of his son was inspired by the “arm and hammer” symbol of the SLP.

Young Armand Hammer, American industrialist and business executive. Photo talen in 1922.

Getty ImagesWhile Hammer was connected to socialism from birth, he at first devoted himself to the pharmaceutical business. During Prohibition, Hammer’s pharmacies were extremely successful, legally selling a ginger alcoholic solution that proved useful for making forbidden alcoholic drinks. Hammer was very skillful at operating on the very edge of the law, and this would always be his trademark.

To Russia with love

In 1921, the 23-year-old Hammer made his first voyage to Soviet Russia. Officially, his goal was to return money paid to purchase medicines that had been shipped to Russia during the Civil War. But after meeting Lenin (and not jumping out the window), the entrepreneur decided it was better to become the human link that connected the new socialist state and American business circles.

The Hammer family knew Ludwig Martens, Lenin’s representative in the U.S., so it was easy for Armand to make friends with the revolutionary leader. He started selling grain to Russia, which was in dire need because of the famine caused by the Civil War, and he supplied more than 1 million tons. But it was just a small part of his business with Russia.

Pencils in, Faberge out

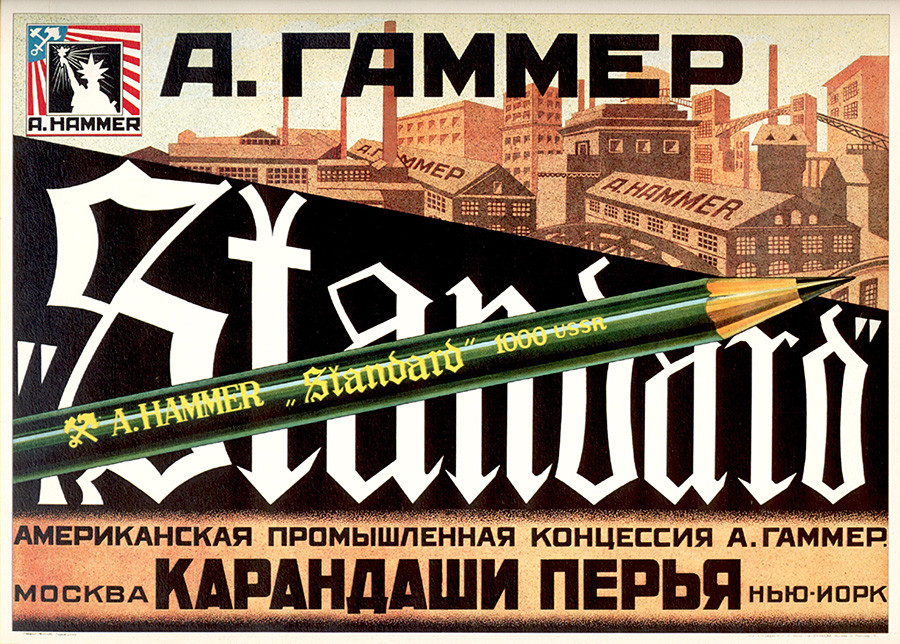

Having secured the favor of Soviet leaders in the early 1920s, Hammer moved to the USSR for a decade and opened several ventures thanks to concession contracts. The largest venture was a factory to produce pens and pencils – an American was basically providing the USSR with writing utensils!

A Soviet advertising poster for Hammer's pencil concession.

Public domainHammer also worked as an intermediary in the USSR, representing major American firms, such as Ford Motor Company and

At the same time, Hammer showed interest in art, also in a commercial way. Taking advantage of the political unrest and chaos in the 1920s, he bought many treasures at favorable prices from Russian state museums, including several Faberge eggs, and resold them at high prices in the West. There’s also a dark side to this art trade, however. In addition to genuine

“When he was bringing his priceless exhibitions to Moscow, art historians were completely confused. No one could tell if they were originals or fakes,” Sovershenno Sekretno magazine wrote.

Back in the USSR

When Stalin came to power, even friendly foreigners such as Hammer were no longer welcomed in the USSR. So, in the early

He met with Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev, gaining the favor of the latter in the 1970s, and his first major project was to build a modern, world-class office center in the USSR, today

This wasn’t Hammer’s only success at that time. He also helped to build the largest nitrogen plant in the

Was he a spy?

Armand Hammer in his office in Los Angeles (1980), with a portrait of Lenin on the background.

ZUMA Press/Global Look PressControversial as he was, Hammer combined his business-first approach with diplomacy and charity, for example, sponsoring medical assistance for Soviet citizens injured in the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986. He was always an important link between the U.S. and the USSR.

“I've been instrumental in trying to bring peace between East and West, and I've been thanked by presidents for what I've done in helping to bring (this) about,” Hammer used to say.

At the same time, it’s still disputed whether he was a Soviet agent. Edward Jay Epstein, author of Dossier: The Secret History of Armand Hammer, claims that Hammer surely was a spy who laundered money for Moscow and financed communist espionage operations. The Soviet security service, however, doubted it.

According to an unnamed Soviet general quoted by Kommersant newspaper, Armand was always ready to talk, but

If you want to know more about the history of Russian-American relations, feel free to read our article concerning the Statue of Liberty and its possible Russian roots.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox