Military units comprised exclusively of women were short-lived in the Russian army, but they have had an everlasting impact on how posterity views the stalwart spirit of Russian women. A few official units were formed in the summer of 1917, and they even saw battle, showing incredible bravery despite heavy casualties. While by autumn they were disbanded, they had set an example and inspired more volunteer female battalions throughout the country.

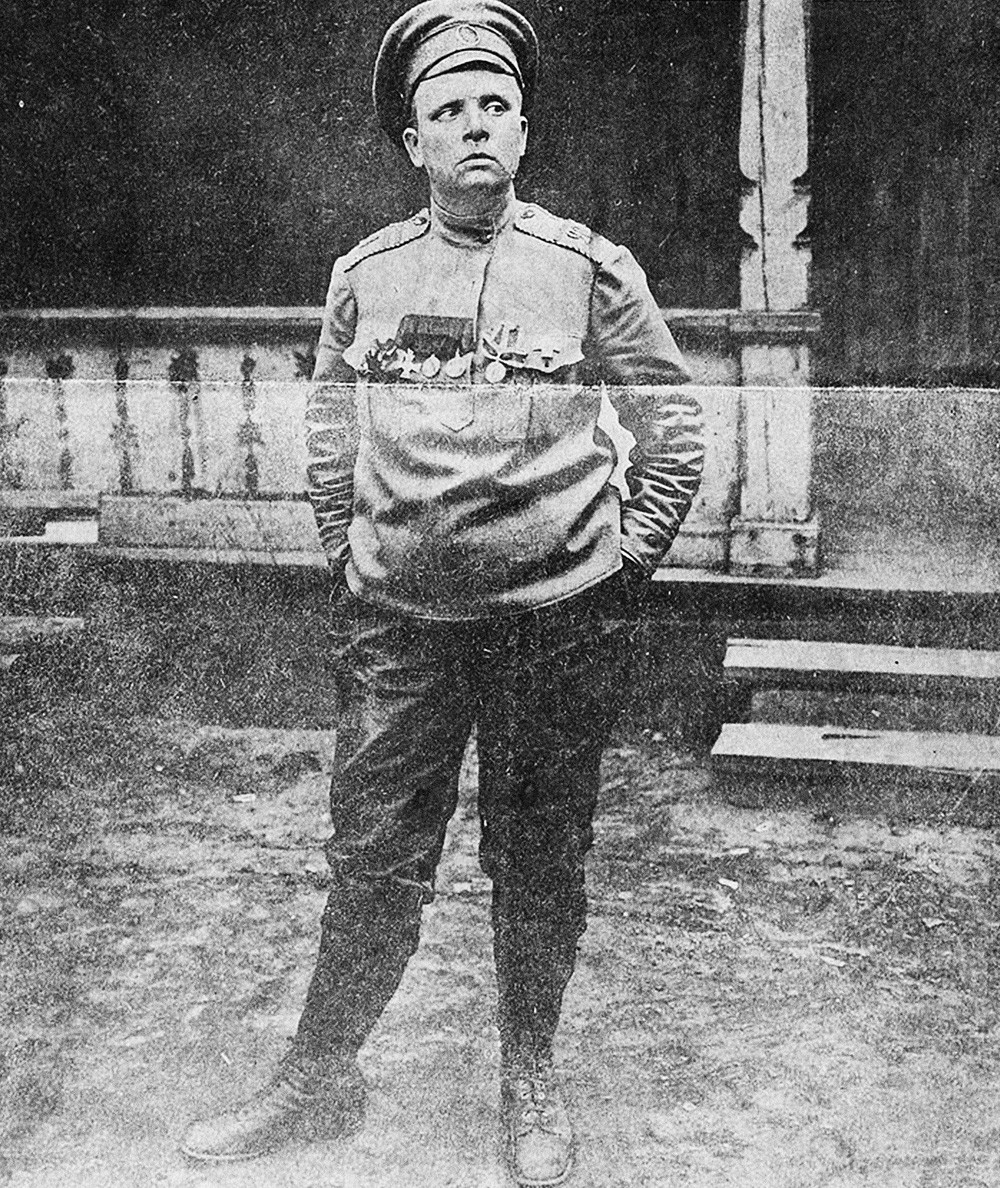

‘Yashka’

Maria Bochkareva, the commander of Women's Death Battalion

SputnikAs often is the case, it all began with a girl who wanted to prove herself. Maria Bochkareva was born into a poor family, and married when she was just 15 years old. Her first husband was a drunkard, and the second, Yakov ‘Yashka’ Buk, turned out to be a gambler and a bandit. In 1914, Bochkareva decided to abandon this life of abuse and join the military.

“My heart was pulling me into the boiling caldron of battle, to be christened by fire and hardened in lava. I was overwhelmed by a sense of self-sacrifice, and my country was calling me,” Bochkareva wrote emotionally in her memoirs. At that time, she could only formally become a nurse, so she wrote directly to the Tsar, asking for permission to fight alongside the men. To her surprise, Nicholas II personally granted that right.

When Bochkareva started her service she was ridiculed and heavily mocked by fellow soldiers. Very soon, however, she became a legend in her regiment, known for fearlessly running into battle where she pulled the wounded from the field, saving over 50 lives.

Like most soldiers at the time, she chose a nickname, ‘Yashka,’ in honor of her husband. For her prowess on the battlefield, she was promoted to the rank of non-commissioned officer (NCO). Even more important, she was recognized by Mikhail Rodzianko, head of the State Duma.

‘We’ll go and die’

With the February Revolution in 1917, the Tsarist government collapsed. Soldiers became demoralized and began to desert. Bochkareva, with support from Rodzianko, came up with the idea to create female ‘death battalions’ to shame and encourage male soldiers to attack. Critics, however, complained that discipline would be low among the women.

“I’ll be responsible for every single woman. There will be harsh discipline and I will prevent them from wandering the streets. Only discipline can save the army. In this battalion, I will have full power and I’ll insist on obedience,” Bochkareva thundered.

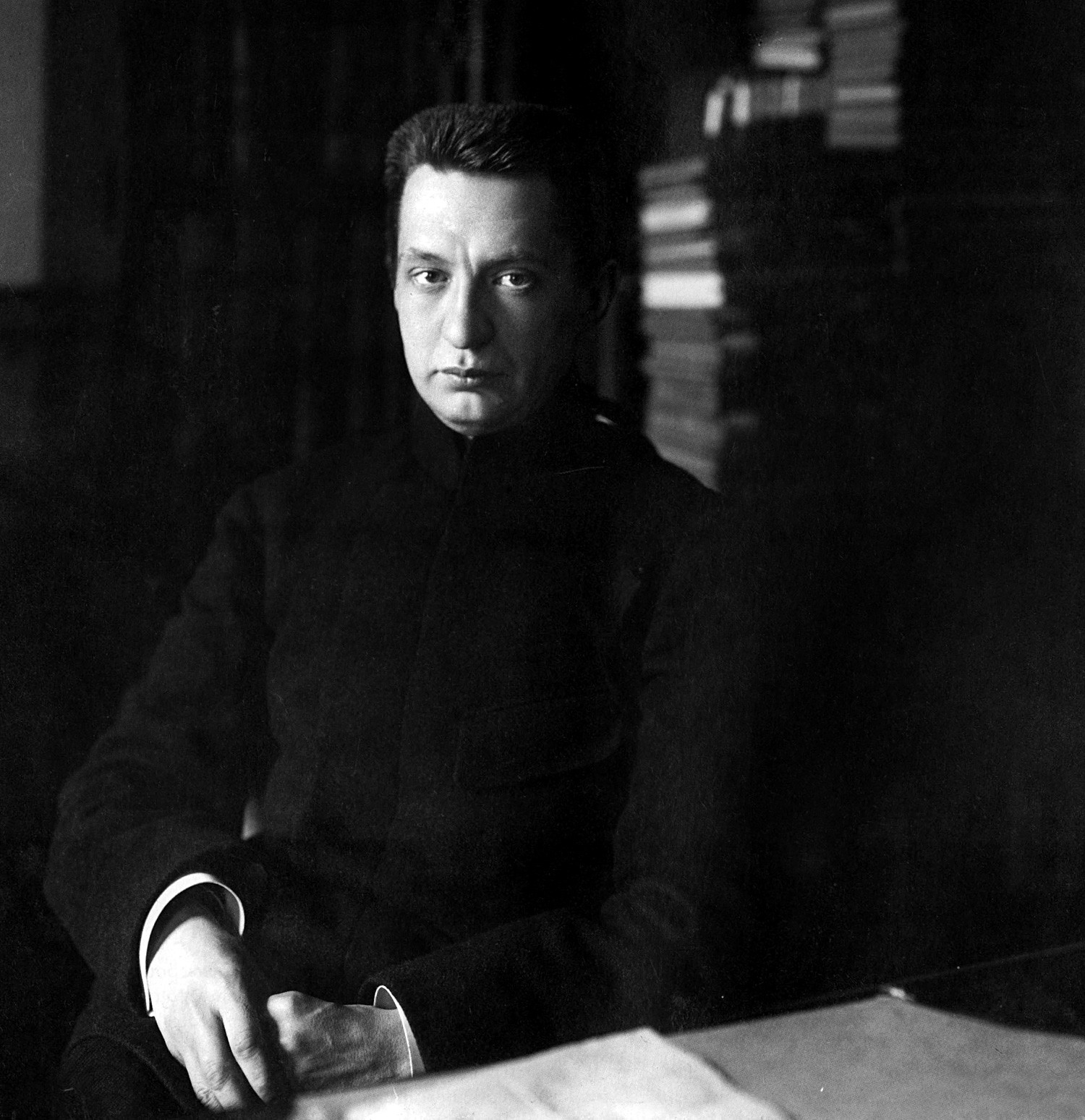

Alexander Kerensky

Getty ImagesAlexander Kerensky, head of the Provisional Government, supported Bochkareva. After the draft was announced, over 2,000 women signed up: nurses, housemaids, peasants, noble women, the uneducated and university graduates. All had to pass a medical exam and their heads were shaved. Then they went to boot camp run by male military instructors where they learned to march, shoot and studied battle tactics, as well as took classes for the illiterate.

Bochkareva wasn’t lying about discipline. In the first two days, almost 80 women were expelled from the battalion for giggling, flirting with instructors and disobedience. In her uniform and with her deadpan face, Bochkareva looked like an old-time military commander and behaved accordingly. She did not hesitate to give her 'girls' a slap on the face for disorderly behavior.

Soon, of the initial 2,000 troops, only 300 remained, all younger than 35. The draft ended, and when answering reporters’ questions Bochkareva replied, “There will be no new draft. We’ll go and die.”

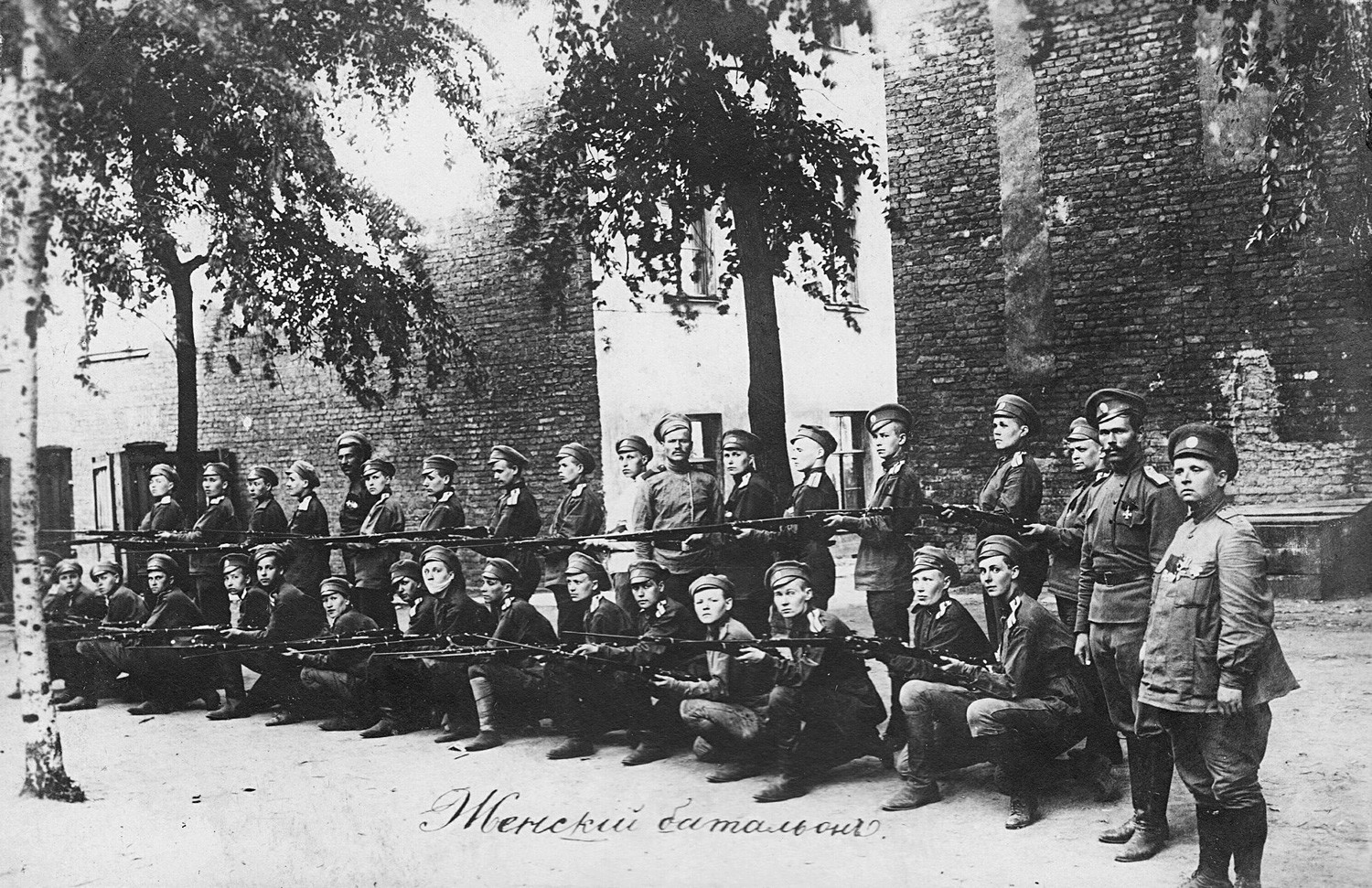

The First Petrograd Women's Battalion of Death, 1917.

Getty ImagesIn June 1917, the 1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death left St. Petersburg for the front lines. On the sleeves of their uniform they wore the Totenkopf (“Dead Head”) symbol, denoting their fearlessness and defiance of death.

A woman’s war

In the army, the new troops were greeted with scorn and were derided as “prostitutes” by male soldiers, says historian Svetlana Solntseva. Anton Denikin, the military commander for the Provisional Government, said “there are many other ways of service that suit women more.” But nothing could stop these women who were determined to fight and defend their country. By October 1917, there were six women’s battalions in Russia, but only Bochkareva’s had the chance to see military action.

July 8, 1917, The 1st Women’s Battalion saw battle near Smorgon (Grodno Region, 500 miles from Moscow). While the men hesitated, Bochkareva’s troops led the charge, encouraging others to join. Over the course of three days, the Russians repelled 14 attacks by the Germans, but eventually they retreated because reinforcements never arrived.

When the fighting was over, of the 170 women who entered the battle 30 had perished and over 70 were wounded. These casualties was used as a pretext to stop the formation of new female battalions, and the existing ones were disbanded by order of Lavr Kornilov, Commander-in-Chief of the Russian army. Those women who still wanted to fight had to file new applications to be accepted into regular units.

General Kornilov inspecting Russian troops, 1st July 1917.

Getty ImagesThere was, however, one female unit that lasted longer than others - the 2nd Company of the 1st Battalion. These were the women initially expelled by Bochkareva, but who remained in the Petrograd Region and formed a second company under Captain Loskov. On Oct. 25, 1917, they defended the Winter Palace against Bolshevik forces, but were outnumbered and defeated. Some of the women were raped by the Bolsheviks, and one woman took her life that night. With the Bolsheviks in power, they hurriedly disbanded all female units for good. Only Bochkareva herself remained a soldier.

American epilogue

Maria Bochkareva with her soldiers.

Getty ImagesAfter suffering a concussion in the battle at Smorgon, Bochkareva spent a month in a Petrograd hospital. Refusing to cooperate with the Bolsheviks, she was accused of counter-revolutionary activity. She was lucky to be able to flee to Europe, and then to the U.S., where she began an anti-Bolshevik campaign. Bochkareva met President Woodrow Wilson, and King George V of Great Britain promised her financial aid.

In 1918, she returned to Arkhangelsk with English troops, and in 1919 she went to Omsk, where she met General Alexander Kolchak, head of his short-lived anti-communist government. Kolchak hoped that Bochkareva would form a women’s battalion in his army, but in January 1920 the Bolsheviks arrested her. Her contacts with Kornilov and Kolchak were enough to condemn her as a “relentless enemy of the proletarian-peasant republic.”

Maria Bochkareva

Getty ImagesBochkareva was shot in May 1920 because the Bolsheviks understood that the leader of a women’s death battalion would never give up fighting her enemies. The sentence was carried out the same day it was made. Only in 1992 did the Russian government rehabilitate Bochkareva.

For more stories on women war heroes, read our article about how two Soviet women became top guns. You may also like a story about the first Russian feminist or the fight for Russian women’s rights.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox