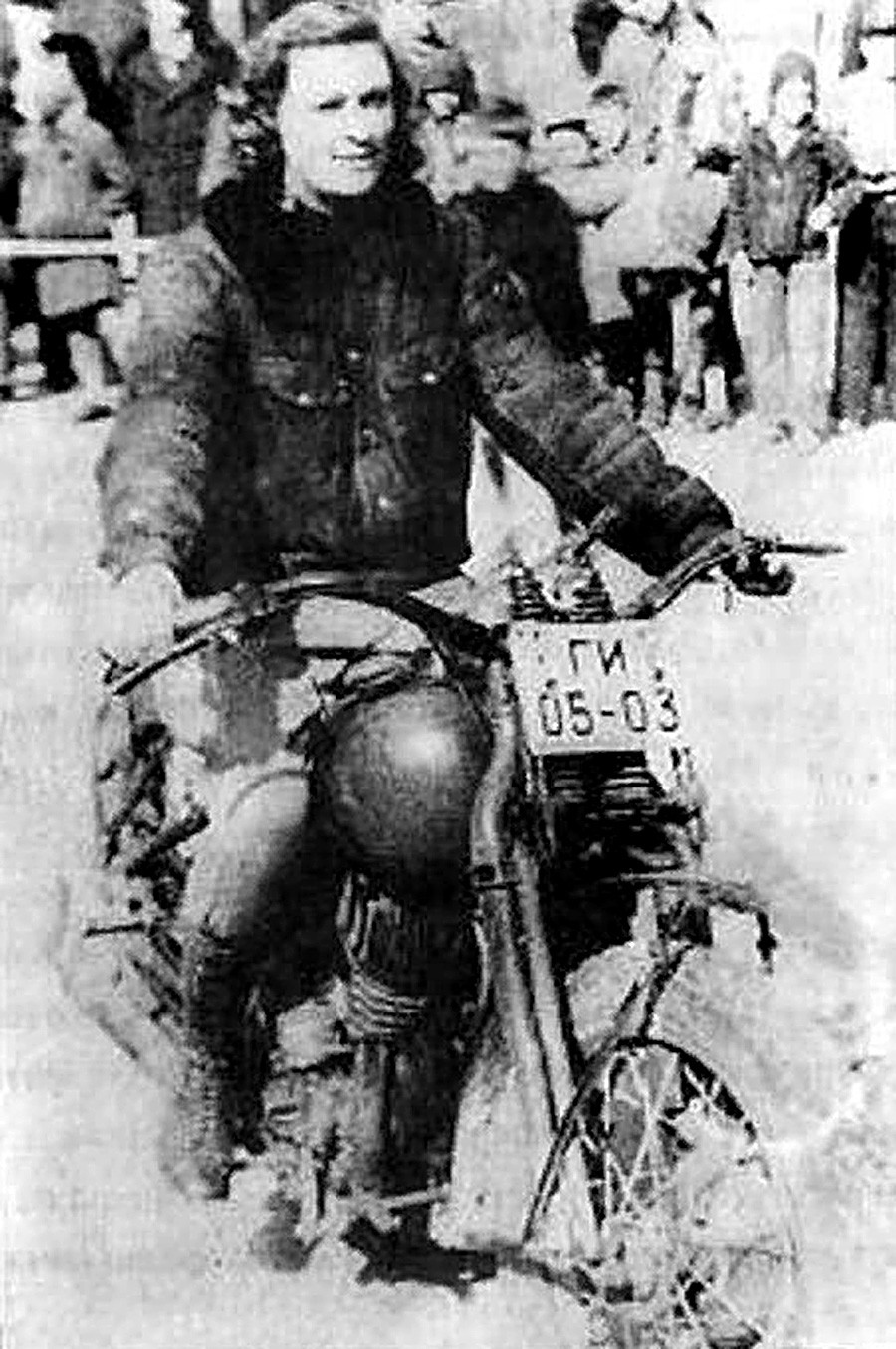

Natalia Androsova (Princess Natalia Alexandrovna Romanovskaya-Iskander), 1940s

Getty ImagesPrincess Natalia Androsova, Tsar Nicholas I’s great-great-granddaughter-

Suspicious past

Before 1917, being born with a title like Princess Iskander-Romanovskaya would have been a golden ticket to a life of utmost luxury. However, Natalia Iskander-Romanovskaya (who became Natalia Nikolaevna Androsova in 1920), was born in the wake of the Revolution, and as a linear descendant of Nicholas I’s disgraced son - the Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich - her family was forced to spend Natalia’s early years in hiding in Tashkent (modern-day Uzbekistan). It was here that her family believed they would be safe following the Bolsheviks’ execution of Duke Nicholas Konstantovich, Natalia’s godfather, in 1918. From Tashkent, the Iskanders watched their family fall one by one at the hands of the Bolsheviks, and when Natalia’s father, Prince Alexander Iskander-Romanov, fled to Greece and then France in 1919 following losses while fighting for the White Army in Tashkent and in the South of Russia, she was left with her mother and brother to face the wrath of the Civil War alone.

In a potentially life-threatening bluff, Natalia’s mother moved the family back to Moscow in 1919 where they occupied a squalid basement in Arbat, right under the Kremlin’s nose, and posed as commoners. The family had been disenfranchised by the Soviet government for being neither peasants nor commoners, but was largely saved from scrutiny by Natalia’s mother’s remarriage to Nikolai Androsov in 1924, which allowed them to adopt his surname.

Natalia lived a largely peaceful childhood in Moscow on the strength of her new identity, but her mother made no attempt to conceal the family’s noble background from her. “To be a granddaughter of the Grand Duke and great-great-granddaughter of Nicholas I was a death sentence,” she once said in a 1996 interview, “but family photographs of the Romanovs always stood in our house.”

Soviet stuntwoman

Natalia Androsova (Princess Natalia Alexandrovna Romanovskaya-Iskander), 1940s

Getty ImagesSimply surviving in the Soviet Union was no easy feat for the last royals left in Russia, but their disenfranchisement, along with positive discrimination of peasants and workers, limited Natalia’s educational and career prospects.

Natalia was undeterred. “The thread between me and my heritage was never broken,” she once said, explaining why she walked with her head held high, and always seemed destined for greatness. Tall, proud, and handsome, she attracted perpetual attention and a reputation as the “Queen of Arbat.” If there was such thing coolness in Stalin-era Russia, Natalia was it. At one point during her teenage years, she was even arrested as a “German saboteur” simply for looking too elegant in a brown velvet jacket, breeches, and heels amidst the stark backdrop of Soviet Moscow.

Since few careers were open to her, Natalia’s love of sport led her to the world of circus entertainment. She took up motorcycle racing on a vertical wall in Moscow’s Gorky Park in 1939, and with her good looks and charisma in mind, her motorcycle exploits were a spectacle to behold. Writer Yuri Negibin described her performances as “terrifying and beautiful, the rumble of the motorcycle, her face turned pale, her eyes widened… She was a goddess, motorcycle racer, and an Amazon.”

Natalia also inspired Soviet poet Andrei Voznesenskiy, who wrote of her:

“The motorcycle a chainsaw over her head,

tired of living upright.

Ah, wild soul, daughter of Icarus.”

Her performances on the “Wall of Death” brought her frequent injuries. “Many times I fell down,” she recalled, “and in the 1940s, I lost one knee. A year later I was back on the Wall of Death again.”

Natalia continued to wow audiences with her stunts for almost thirty years, interrupted only by WWII. The fearless stunt woman took a wartime diffusing German bombs, and another delivering bread to Soviet troops on the front.

Skeptical spy

Unsurprisingly, Natalia’s bohemian “Queen of Arbat” profile did not go unnoticed during Stalin’s purges. As a traveling performer, Natalia was spared the constant supervision to which most Soviet citizens were subject, but evidently boasted of her imperial lineage one too many times: In 1939, her cover was blown when a man who knew about her ancestry tried to blackmail her for sex. As revealed in John Curtis Perry and Constantine Pleshakov’s book The Flight of the Romanovs, Natalia actually slapped the man across the face, and in doing so brought unwanted NKVD attention upon herself.

In spite of her princess status, Natalia was not treated by the secret police with the same brutality shown to millions of others. Instead of sentencing her to a labor camp, it seems Natalia’s agents at the Lubyanka were immensely charmed by the Romanov princess, and actively tried to recruit her. Indeed, Natalia’s NKVD profile was later revealed to be extremely flattering, describing her as “young, intelligent, and attractive.” Her only problem was that she refused to cooperate with the secret police, telling them that she “had no desire to learn how to squeal on others.”

However, with the NKVD now aware of Natalia’s roots, turning them down wasn’t an option. Natalia’s sole mission involved an elaborate assignment to seduce a French diplomat in Crimea under the codename “Lola.” Having followed him from Moscow and orchestrated a breakdown of his car in which Natalia was to swoop in to help him, the dignitary didn’t take the bait.

Natalia failed to impress as a spy, and was left by the secret services to continue thrilling crowds as a stuntwoman, which she excelled at until her retirement in 1964. She lived out the rest of her life in peace, marrying film director Nikolai Dostal in the 1950s. Natalia never had children to continue the Romanov line on her side, but raised Nikolai’s two sons alone when she became widowed after two years of marriage. She was even allowed contact with her father’s family in France following Khrushchev’s thaw, and upon visiting her father’s grave in Nice after the fall of the Soviet Union, she declared that she had “fulfilled everything” in life.

Natalia never got to experience her would-be life as a Romanov princess. However, while her material wealth said she was a commoner, she had the soul of a royal, and stayed as true as possible to the Romanov persona within the confines of the Soviet Union. What’s more, this confidence, daring and independence with which she went about her life showed unthinkable belligerence in the face of a system that demanded docility, and gave quiet protest to the regime that tore her family apart. In 1996, when asked if she was afraid of the gunshots she heart on the street she responded with pride, “No, I have never been afraid of anything.”

She passed away in 1999, at the age of 82.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox