The A. I. Abrikosov & Sons Company

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovThe A. I. Abrikosov & Sons Company is an important candy company with a long history and one of the largest factories in Moscow. Other large factories include Einem (the current Red October), the Lenovykh trading house (RotFront) and Siu and К° (the Bolshevik Factory). However, few people know that this company’s story began with small simple treats that the owner prepared for his landlady.

A serf by the name of Stepan from a little village in the Penza Governorate used to make sweets from fruits and berries for his landlady. He would use items growing in his peasant garden to make the treats. The apricot jam and candy came out particularly well. As was generally the case with serfs, Stepan did not have

Penza in the early 20th century

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovThe Abrikosovs worked together as a whole family, which consisted of Stepan, his wife Fekla Ivanovna and their children Ivan, Vasily

After Stepan’s death, his son Ivan Stepanovich took control of the business and then, after him, Stepan’s grandson, Alexei Ivanovich Abrikosov. The family continues to prosper, and production has expanded and been mechanized. The factory first used machines to grate almonds and press

Abrikosov's candies

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovThe volume of production has also increased. In 1871, the factory’s annual production was 445 tons, and by 1872 it was 512 tons. The A. I. Abrikosov enterprise became one of the largest candy producers in Russia, along with Einem (Red October after the Revolution), Siu and К° (the Bolshevik Factory after the Revolution) and others.

Competition in the candy market forced the Abrikosovs to continue to improve on production.

In 1873, the company acquired a steam machine, which divided production up into factory sections.

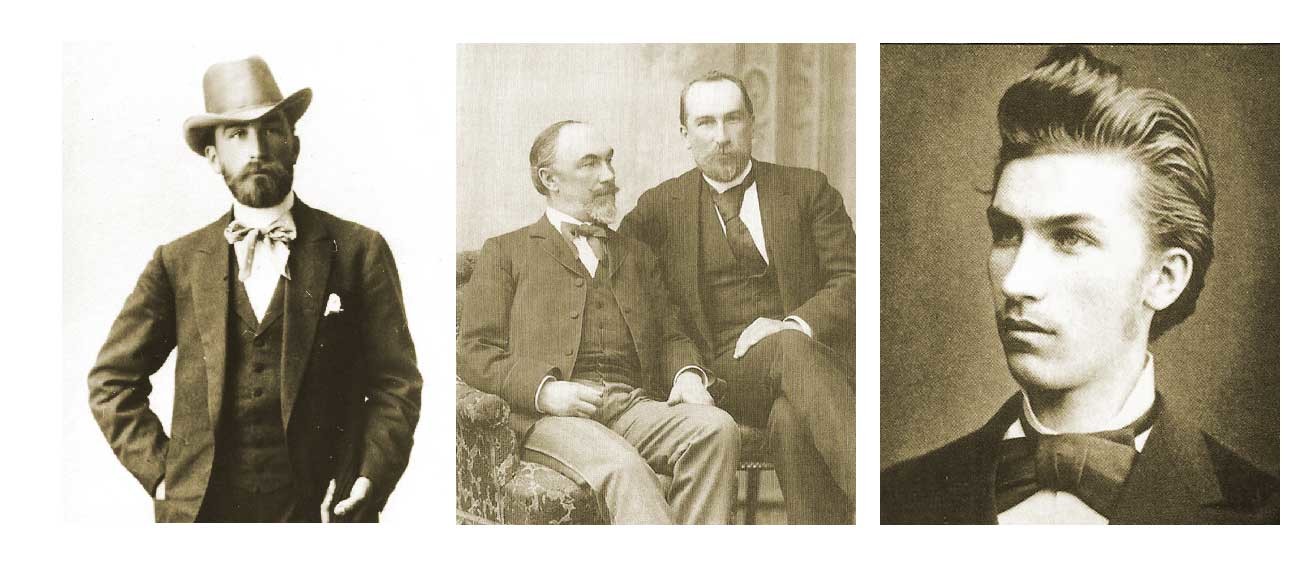

Pictured L-R: Alexei Abrikosov, brothers Alexei and Nikolai Abrikosov, Ivan Abrikosov (son of Alexei)

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovThe Abrikosovs were a big happy family. In total, Alexei Ivanovich and Agrippina Alexandrovna had 22 children: 10 sons and 12 daughters. In 1874, Alexei Ivanovich transferred control of the company to his sons, Nikolai and Ivan.

In the 1880s, the Abrikosov company became the largest candy enterprise in Moscow and one of the five leading companies in Russia, producing 50 percent of all candy in the country. Besides Moscow and St. Petersburg, the company had stores in Kiev, Odessa, Rostov-on-Don and Nizhny Novgorod. A branch of the factory opened in Simferopol, Crimea. It produced jam, compote, chestnuts in sugar, marzipan

To increase sales, the Abrikosovs advertised actively, placing ads in newspapers, hanging vivid posters on building facades and distributing pocket calendars with the company logo. Significant attention was paid to the relationship between the salesperson and the customer. But the company’s biggest pride was the packaging.

Abrikosov's candies

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovThe multi-form metallic, cardboard and wooden boxes and cans with original drawings outlived the sweets inside. Not wanting to discard these beautiful objects, the customer often held on to them as a jar for collecting coins or simply to embellishing their home.

In 1899, the A. I. Abrikosov & Sons Company, having won first place at the All-Russian Artistic-Industrial Exhibition for the third time and was awarded the honorary title of Supplier of His Imperial Majesty, allowing them to depict the House of Romanov coat of arms on its packages. To obtain this right the company had to produce for the state for ten years straight and not once “fall with its face in the mud.” For the customers, the Abrikosov sign became an original symbol of quality.

The factory is composed of several brick buildings on the corner of Bolshoi and

Abrikosov's factory

Courtesy of Dmitry Abrikosov

Abrikosov's factory

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovThe 1917 October Revolution and the Civil War both disrupted the activities of the A. I. Abrikosov & Sons Company. Production volumes declined substantially, and in 1918 the factory was nationalized and its name changed to State Confectionary Factory No. 2. In 1922, the factory became affiliated with the name Petr Akimovich Babaev, the chairman of the executive committee of the Sokolniki district, and was called the P.A. Babaev Worker Factory. However, “former Abrikosov” was added to the packaging. This old trademark, which guaranteed quality, helped keep the customers.

In 1928, the Moscow confectionary factories began dividing up the company’s product range. Chocolate was made at the Red October plant, cookies at the Bolshevik plant and the Babaev factory made only caramel. Special apparatuses were ordered from Germany to brew caramel syrup.

This avant-garde mansion for Abrikosov's factory in Moscow was built by architect Boris Shnaubert, now the building hosts the Babaev factory.

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovWhen the war began, many workers and experts at the factory went off to the front.

As reparations for the war, Germany sent industrial equipment from its factories, including confectionary operations, to the Soviet Union. Some of this equipment was given to the Babaev factory for its chocolate production. Gradually, the chocolate division grew, and by the beginning of the

Legendary 'Montpensier' pastille

Courtesy of Dmitry AbrikosovThe beginning of the 1990s was a difficult time for the confectionary factory. Due to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the established agricultural relationships between businesses and the former Soviet republics—which supplied raw materials—fell apart. Production volumes fell, but despite everything the factory continued working and by the end of the 1990s the Babaevsky Confectionary Corporation had made a comeback by churning out candy with the Soviet brand names Alenka, Vdokhnovenie, Radii

In 1993, the descendants of Alexei Ivanovich Abrikosov brought back the family business and created a new A. I. Abrikosov & Sons Company.

Read more: What street food looked like in Moscow 100 years ago

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox