Catherine the Great

Getty ImagesRussia welcomed foreigners long before Empress Catherine the Great’s manifesto of July 22, 1763. Ivan III, the first ruler of the centralized Russian state, eagerly used the services of non-Russian specialists who helped him to rebuild the Kremlin and organize the production of cannons in the late 15th century.

Fifty years later, the tsar with the scary name – “the Terrible” – also resorted to foreigners’ assistance when he decided to set up his own fleet on the Baltic Sea. Peter I, the founder of the Russian Empire in the early 18th century, was bitterly criticized by his fellow countrymen for what they thought was over-reliance on European specialists regarding his policy.

Why did the Empress invite foreigners?

Catherine II’s inviting of colonists from Europe was an unprecedented move in Russia. Due to the scale of this initiative she managed to attract tens of thousands of foreign settlers. Why did she do it? Let’s turn to the manifesto for the answer.

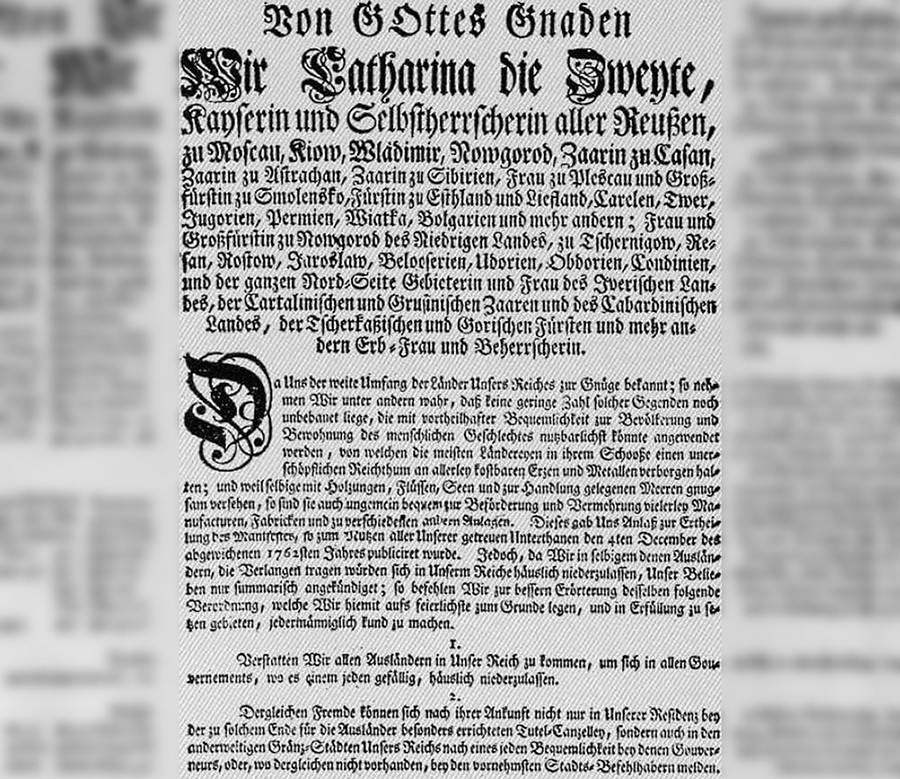

Catherine the Great’s manifesto of July 22, 1763

Public DomainThere the empress highlighted that the government “sees a lot of the most suitable living places still being uninhabited while many of them hide in their depths the endless multitude of different metals, as well as possess forests, rivers, lakes, and seas … and have great potential for increasing a number of factories and other plants.”

During Catherine’s reign, vast territories in the south and southeast were incorporated into the Empire. Even without the new conquests, there were huge regions that were scarcely populated. To bring people to those territories and make them a more significant part of the national economy was the empress’ objective.

Belgium advertising of concentrated meat broth featuring Catherine the Great on her way to her Oranienbaum palace in St. Petersburg in 1762, Companie Liebig 1990.

Public DomainThe manifesto was translated into several European languages and was distributed through Russian diplomatic agents in European countries and published them in local newspapers.

To make people interested in the offer the Russian state provided benefits. Colonists were guaranteed a decent plot of land (there were also some additional lots for their offspring). They were granted a remission of taxation for a number of years (up to 30 years if they chose to stay in the countryside) and were freed from military service.

They were also given the right of autonomy – the imperial administration could not interfere in the internal affairs of their communities. Plus, they were given money for relocation and some soft loans and benefits for the products they produced and sold. One might say that local Russians never enjoyed such a status.

Probably, one of the most important reasons why foreigners chose to settle in the country was because they were free to worship and build their own churches. It was a key factor for many German Protestants who felt uneasy living in Catholic-dominated territories.

First government of German Autonomous Territory

Public DomainTherefore, Protestants, especially Mennonites, made up a big chunk of the total number of people who took up the empress’ offer.

In the first decade after the manifesto was issued around 30,000 people settled in Russia. They were mainly Germans who chose the scarcely populated Volga region. In 1765 there were only 12 colonies there, but just four years later the number grew up to 105. The main occupation of the German colonists was agriculture and some branches of manufacturing that were closely tied to it. It was no surprise as Catherine consciously “made the main stress on agriculture… That is why the main working force that should be brought to Russia she sees in peasants bankrupted as a result of the Seven Years’ War,” as Russian historian Irina Cherkozyanova underlines.

Another popular region where foreigners settled was the territory that currently belongs to Ukraine – at the time it had just been conquered from Turkey’s vast lands stretching along the Black Sea coast. It was called Novorossiya (The New Russia). These were the sites where many Christians (Serbs, Greeks, Armenians) who fled from Turkey to Russia chose to live. During Catherine’s rule some 100,000 foreigners moved to Russia.

Read more: Putin suggests free visas for football fans' relatives and friends

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox