The approach of historians, both in the U.S. and Russia, toward the Cold War’s origins have evolved over time. First, the two sides relentlessly blamed each other. Then, they tried to come up with more compromising theories. In the 1990s, however, the situation in the U.S. took a peculiar turn with the revival of the post-war orthodox stance.

This is clearly the case with John Lewis Gaddis, a researcher who has been labeled the “dean of Cold War historians.” A Yale University professor and holder of many honors, including the Pulitzer Prize, he is considered “one of America’s leading historians,” and even advised the White House when George W. Bush was president.

Gaddis started as a historian who argued that too much blame was assigned to the U.S. on the issue of the Cold War’s origins. He ended up considering Soviet ruler Josef Stalin to be the ultimate driving force behind the conflict.

Gaddis describes the reasons for the Cold War’s beginning, “The conflict existed in the ambitious hopes and paranoid fears of Josef Stalin on the Soviet side, and the determination of the U.S and its Western allies to oppose those ambitions to the extent that they existed beyond the gains achieved by the Soviet army in World War II.”

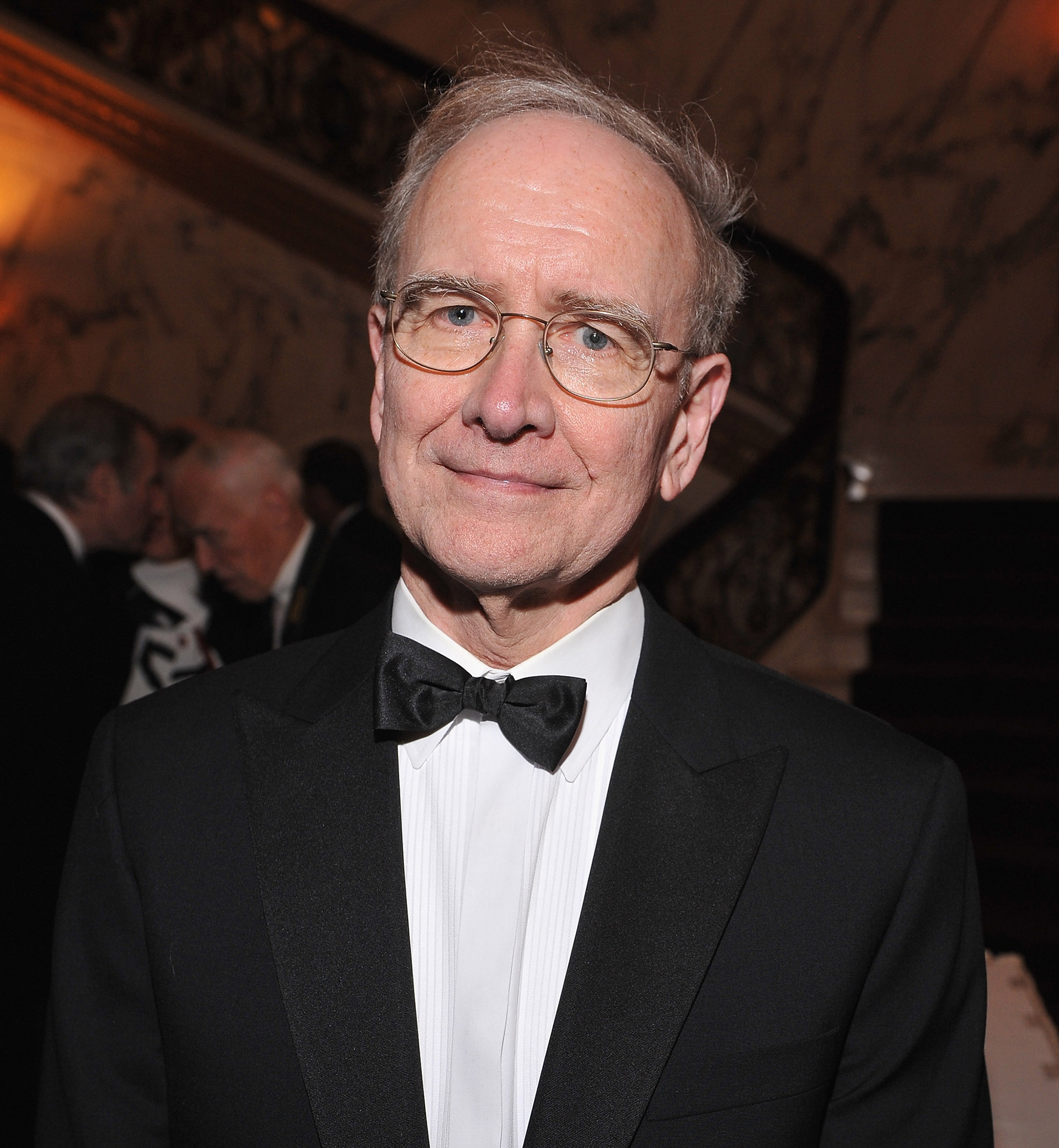

In his

John Lewis Gaddis

Getty ImagesIn Gaddis‘ view, Roosevelt and Churchill envisaged a postwar settlement that “assumed the possibility of compatible interests, even among competing systems.”

Stalin, on the other hand, aspired to “secure his own and his country's security while simultaneously encouraging rivalries among capitalists.” He sees no place for cooperation and mutual co-existence, assigning blame to Stalin.

The historian also contrasts the two countries. Gaddis argues that “… the citizens of the United States could plausibly claim, in 1945, to live in the freest society on the face of the earth.” On the other hand, the USSR “was, at the end of World War II, the most authoritarian society anywhere on the face of the earth.”

The Cold War is cast as a showdown between Freedom and Authoritarianism, where the latter is obviously the bad guy responsible for the conflict.

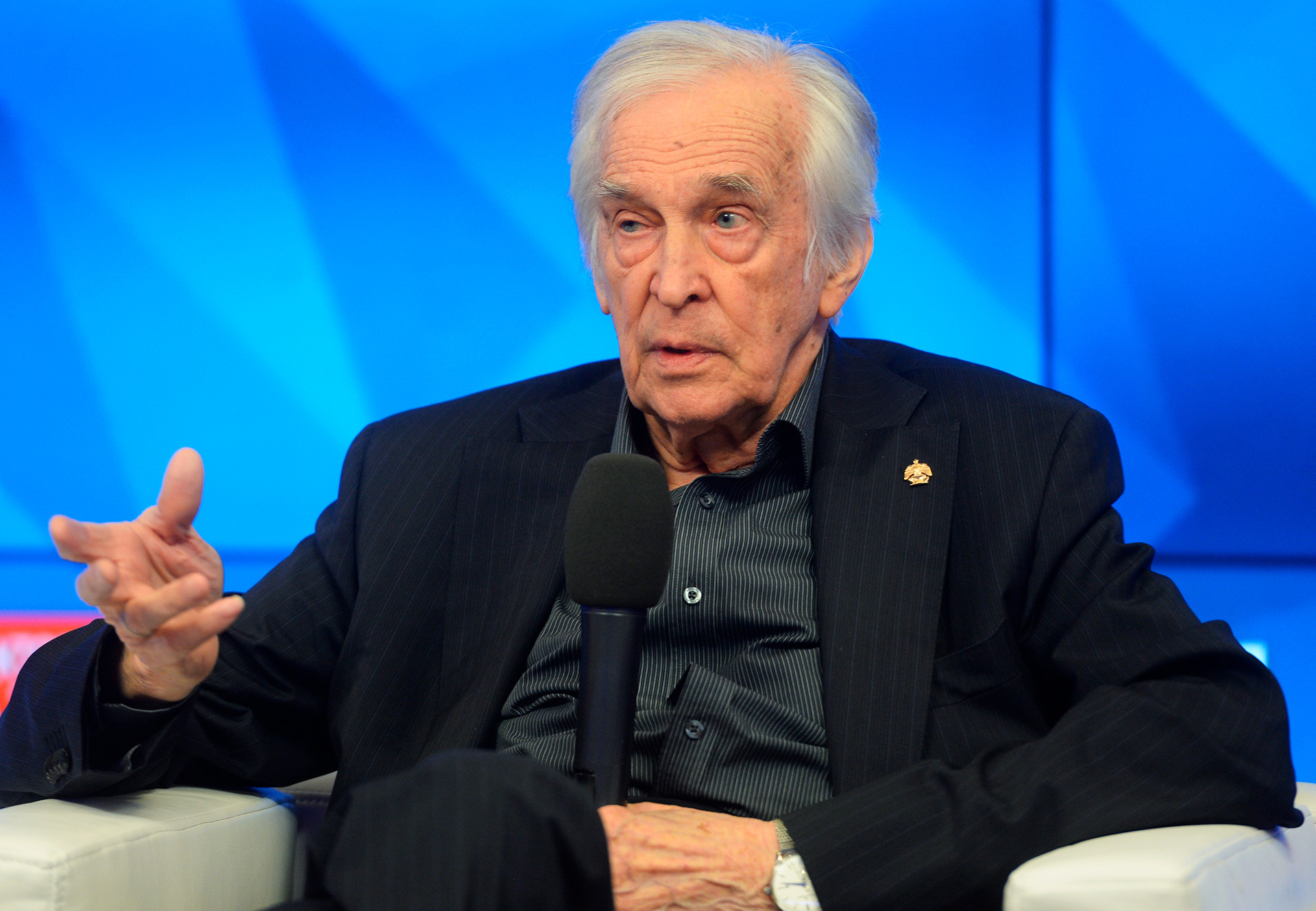

Arguably, on the Russian

Valentin Falin

Grigoriy Sisoev/SputnikThe historian cited the words that Roosevelt said in his speech to Congress on March 1,

The "Big Three" at the Yalta Conference. In the picture: (right to left) Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill

Global Look PressAccording to Falin, “the world that Franklin Roosevelt described did not meet the expectations of the reactionary faction in Washington that was getting stronger,” and when Roosevelt died, his successor, Harry Truman, did not want to take into account the interests of other nations. Already in April that year, he declared that “this [the cooperation between Moscow and Washington] should be broken now ...”

To illustrate the new and hostile course of the U.S. administration towards Moscow that was fanning the flames of the Cold War, Falin referred to the Pentagon’s military planning activity. He cites Memorandum 329 of the American Joint Intelligence Committee from Sept. 4, 1945, just a couple of days after the end of the war

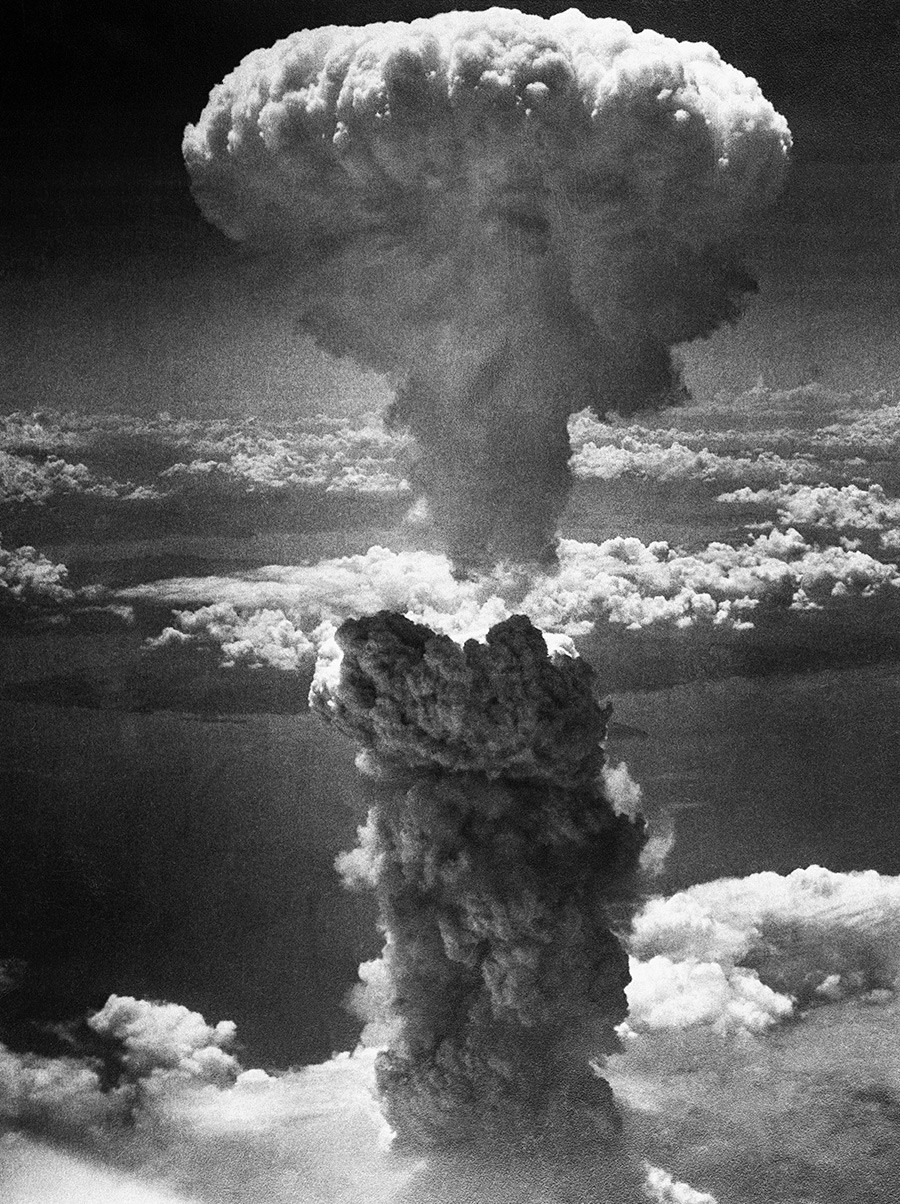

A mushroom cloud towers 20,000 feet above Nagasaki, Japan, following a second nuclear attack by the United States on August 9, 1945

Getty ImagesBy that time, Washington had already possessed the bomb for several months and even used it in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Until 1949, the USSR lacked nuclear weapons. The memorandum was just the first in a long list of such documents.

Read here how the USSR and U.S. battled each other with radio waves

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox