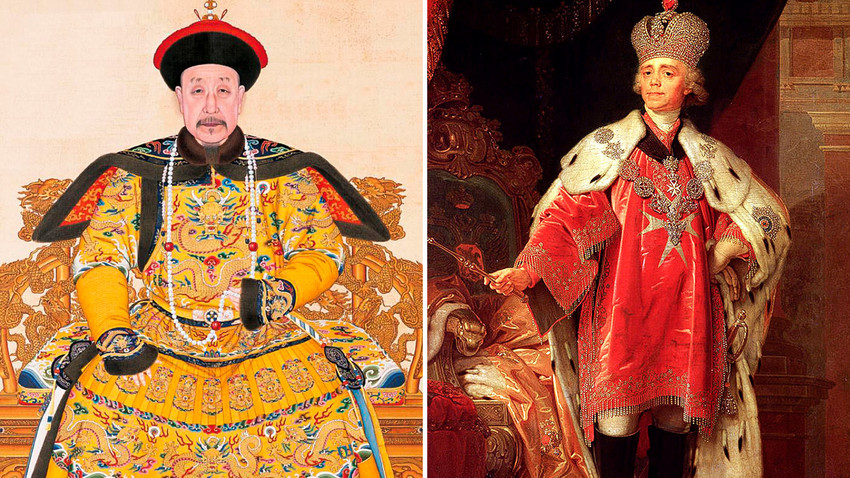

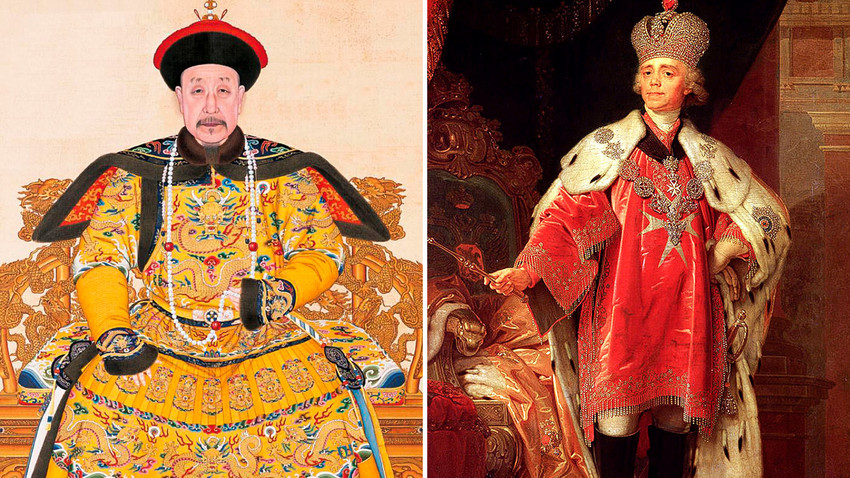

Left: Portrait of Qianlong Emperor of China (reigned in 1736-1796). Right: Portrait of Emperor Paul I of Russia (reigned in 1796-1801) in his coronation robes.

Wang Jin, The Palace Museum / Vladimir Borovikovsky, The State Russian MuseumThe fate of China’s Qing dynasty (1644-1912) eerily echoes that of the Romanovs. How was it that this ancient land, imbued with Confucianism, came to develop almost in parallel with the young Russian state to the north?

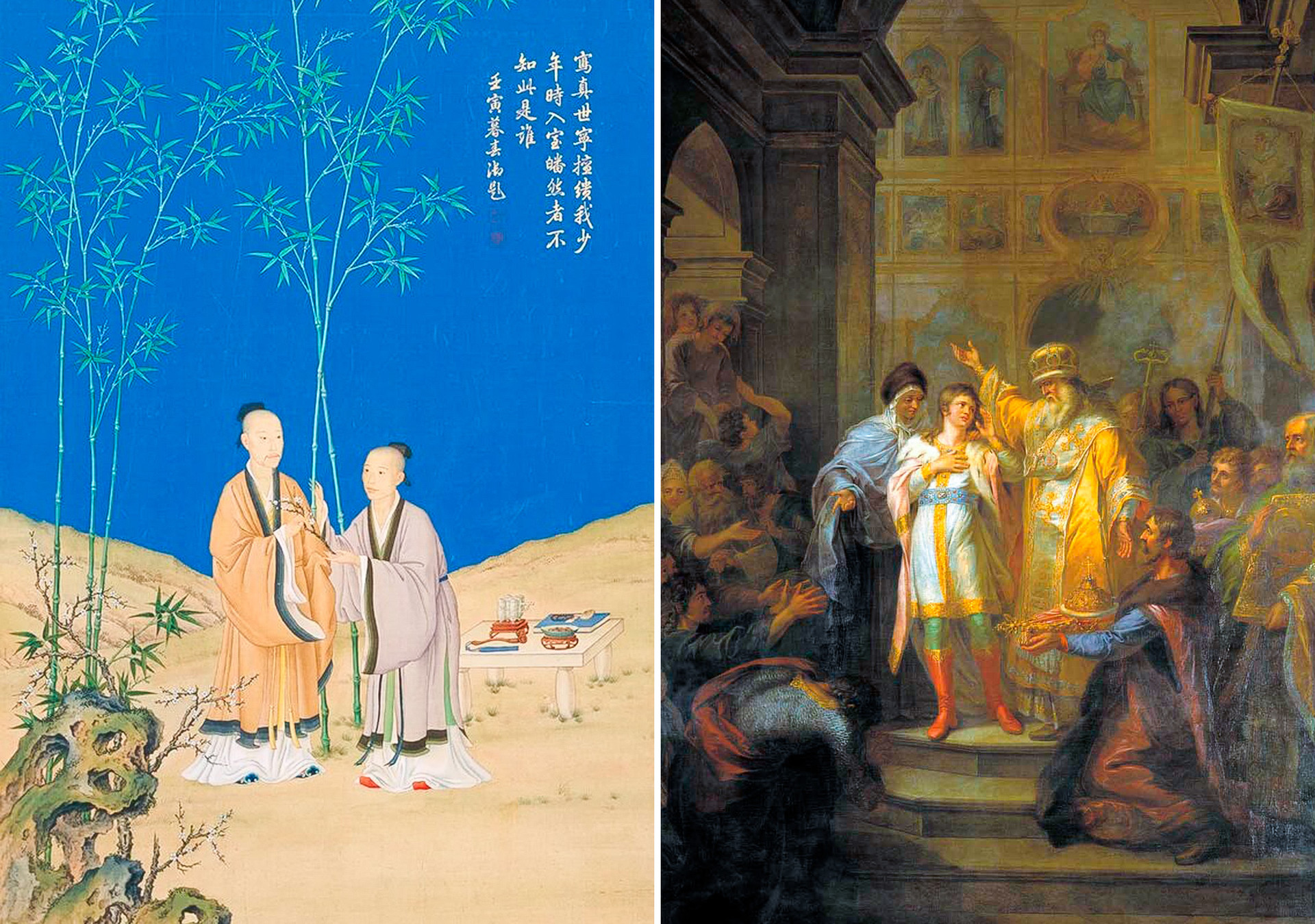

Left: "Message of the Serene Spring" by Lang Shining, the Quing era (1736-1796). Right: "Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov being summoned to the throne" by Grigory Ugryumov.

The Palace Museum/Wang Jin / Grigory Ugryumov/Tretyakov Galleryfirst eye-catching similarity is the temporal proximity of the Romanov and Qing monarchs. The first ruler of the Romanov dynasty, Mikhail Fedorovich, ascended to the Russian throne in 1613. Just a few decades later, in 1644, having defeated the forces of the previous Ming dynasty, the young emperor Shunzhi, the first ruler from the House of Qing, took power in Beijing. What is more, Qing and Romanov rule came to a shuddering halt within five short years of each other (1912 and 1917, respectively) — both imperial houses were swept away by revolution.

Yet there are differences. The Qing monarchs in China were outsiders — natives of Manchuria, they effectively conquered China by taking advantage of the Ming dynasty’s weakness and unpopularity and winning the majority of the population over to their side. The Romanovs, on the contrary, fought off foreign invaders from Sweden and Poland during the Time of Troubles, following the death of Ivan the Terrible. Nevertheless, both dynasties built their states on the fragments of the past: the Romanovs on the Rurik Tsardom, and the Qing on the Ming Empire. Both had a lot of rebuilding to do.

In Russia, the man who changed everything was Peter the Great (reigned 1682-1725). It was he who proclaimed Russia as an empire (China had proudly worn this label since 221 BC), carried out far-reaching reforms, and, as a result of the Great Northern War (1700-1721) against Sweden, turned Russia into a full-fledged European power.

Left: Emperor's throne from the Quing era (1644-1912). Right: The throne of Paul I of Russia.

The Palace Museum/Wang Jin / Dave Bartruff/Global Look PressIn China, the first emperors of the Qing dynasty also sought, as far as feasible, to modernize the country. It was the Emperor Kangxi (reigned 1661-1722) who introduced a tax reform that freed the peasants from overtaxation, which led to economic growth and a demographic explosion. The Chinese, like the Russians, were forced to wage war against European countries — in the late 17th century, they defeated the Dutch occupiers of Taiwan.

Left: Emperor's blue robe made of silk from the Jiaqing period (1735-1796). Right: The coronation costume of Alexander I of Russia.

The palace Museum/Wang Jin / Shakko/wikipediaThe Qing conquests were not limited to Taiwan, however. China’s new rulers expanded the territory of their empire to take in Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet. The Romanovs, in turn, annexed ever more lands to the burgeoning Russian Empire: in the 18th and 19th centuries, this giant entity extended its reach from Poland to the Kuril Islands, swallowing even Alaska.

Left: Empress of China's grand robe of the Quing era. Right: Coronation dress of one of Russia's Empresses.

The Palace Museum/Wang Jin / Igor Zarembo/SputnikThus, throughout the 17th-18th centuries, both the Romanovs and the Qing were major centers of power. The fates of hundreds of millions of people and vast territories lay in the hands of the Russian and Chinese emperors. It is hardly surprising, then, that the interests of these two goliaths began to overlap — and not without friction.

The main bone of contention for Russia and China at the end of the 17th century was the Amur basin, north of the Chinese lands, where Russian immigrants were settling the uninhabited terrain and building the first fortifications. The Qing emperors, wary of Russian expansionism, considered these lands their own, despite the minimal Chinese population there.

Left: Chinese dagger of the Quing era, the Palace Museum. Right: Russian dagger. Zlatoust. Late XIX c. State Historical Museum. Moscow.

The Palace Museum/Wang Jin / Global Look PressAfter a brief war in the 1680s, Russia and China signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, which was more beneficial to China. As a result, Russia temporarily shelved plans to develop the Amur region and the Far East.

In the 18th century, the Qing dynasty succeeded in consolidating its power and bringing about an economic recovery. Effectively self-sufficient by now, China became a major exporter of textiles and porcelain. Nor did the emperors neglect culture, restoring literary monuments of past epochs and compiling dictionaries and encyclopedias.

Left: Chinese Baofu vase of the Quing era, Qianlong period. Right: Russian Gzhel jug, 18th century.

The Palace Museum/Wang Jin / A. Sverdlov/SputnikDespite that, China remained an agrarian country, closed off from the outside world and largely unfamiliar with modern inventions and agricultural methods.

Left: Emperor's seal of the Qianlong period. Right: State seal of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia.

The Palace Museum/Wang Jin / Vladimir Fedorenko/SputnikRussia in the 18th century saw the era of palace coups replaced by the “enlightened absolutism” of Catherine the Great. It became a more open and European state, but the absolute power of the monarch and the reliance on an agrarian economy stood firm. The contradictions between the external sheen and the deep internal problems persisted in both countries, which led to dire consequences. It was Qing China, however, that encountered them earlier — and suffered more.

In the mid-19th century, both St. Petersburg and Beijing fought wars against Western powers and lost. Russian defeat came in the Crimean War of 1853-1856 against Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire, while Qing China was powerless to resist Britain and France in the so-called Opium Wars (1840s-50s), when a series of treaties imposed on China turned the country into a de facto colony of the West. Grasping the moment, Russia persuaded China to sign the Beijing agreements, under which it secured the rights to the Amur and Primorye regions.

Left: White Tara statue, the Qianlong period. Right: Russian Jesus icon of 1677.

The Palace Museum/Wang Jin / Simon Ushakov/WikipediaThe Russian Empire, despite heroic failure in the Crimean War, continued to exist relatively problem-free for another six decades. Meanwhile, Qing attempts to reform and revitalize the Chinese economy were shaken to the core by popular uprisings that lasted for decades; the last emperors were more figureheads than rulers, with real power lying in foreign hands.

Left: Portrait of Qianlong Emperor of China (reigned in 1736-1796). Right: Portrait of Emperor Paul I of Russia (reigned in 1796-1801) in his coronation robes.

Wang Jin, The Palace Museum / Vladimir Borovikovsky, The State Russian MuseumIn the 1910s, revolution erased both empires from the world map: the Xinhai Revolution of 1911-12 in China, and the February Revolution of 1917 in Russia. The imperial houses of Romanov and Qing fell, and from the chaos that both civilizations plunged into, Russia and China were pulled out by people of a wholly different breed.

From March 15, the “Treasures from the Palace Museum: The Flourishing of China in the 18th Century” exhibition is open at the Moscow Kremlin Museums. If you happen to be in Moscow, take the time to see some magnificent Qing dynasty treasures: ceremonial garments, portraits of Chinese emperors, their regalia and personal items—from jewelry to tableware. See here for more details:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox