The Soviet Union was the only country in the world where Coca-Cola lost the market to its eternal opponent.

The Soviets first got acquainted with Coca-Cola in the 1930s, when an official delegation visited America. Colonizing the USSR with the iconic U.S. brand was deemed too expensive at the time, but there was an idea to set up production lines with completely different ingredients. Instead of coca leaves Georgian tea was proposed. However, the new drink - Ruscola as it was dubbed - would never see the light of day.

After World War II, Coca-Cola had a chance to get inside the Soviet bloc thanks to a famous personality. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, one the war's most famous Soviet generals, had developed a taste for Coke, after being introduced to the fizzy concoction by Allied forces commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Zhukov, however, couldn’t openly drink an American branded drink. He asked the company to create a special Cola, colorless like vodka, and not in such a “funny-looking bottle.” Soon he got dozens of bottles of White Coke, topped with a red star on the crown cap.

Zhukov didn’t try to promote Coca-Cola in the USSR, preferring to keep it for personal use only.

Coca-Cola seemed destined to enter the Soviet market - but old rivals PepsiCo were to beat the company to it.

In 1959, at the U.S. National Exhibition in Moscow, vice-president Richard Nixon did a favor for his friend, Pepsi CEO Donald McIntosh "Don" Kendall, and guided Nikita Khrushchev to the Pepsi stand. The Soviet leader was so amazed with the drink that he drank half a dozen glasses.

A photo of Khrushchev with a Pepsi cup covered the front pages the next day - giving the brand a massive boost. “Khrushchev wants to be sociable,” echoed Pepsi’s U.S. advertising of the time: “Be sociable, have a Pepsi.” It was a big blow for Coca-Cola.

Negotiations to bring Pepsi to the Soviet Union took more than a decade: the drink only arrived in 1972, when PepsiCo started supplying concentrate and equipment for future factories. The first Pepsi plant opened in Novorossiysk on the Black Sea coast in 1974.

Monetising the drink proved more difficult. Soviet rubles were not traded internationally, since the Kremlin forbade currency exports. The solution was to use barter. Pepsi concentrate was swapped for Stolichnaya vodka and the popular spirit's U.S. distribution rights.

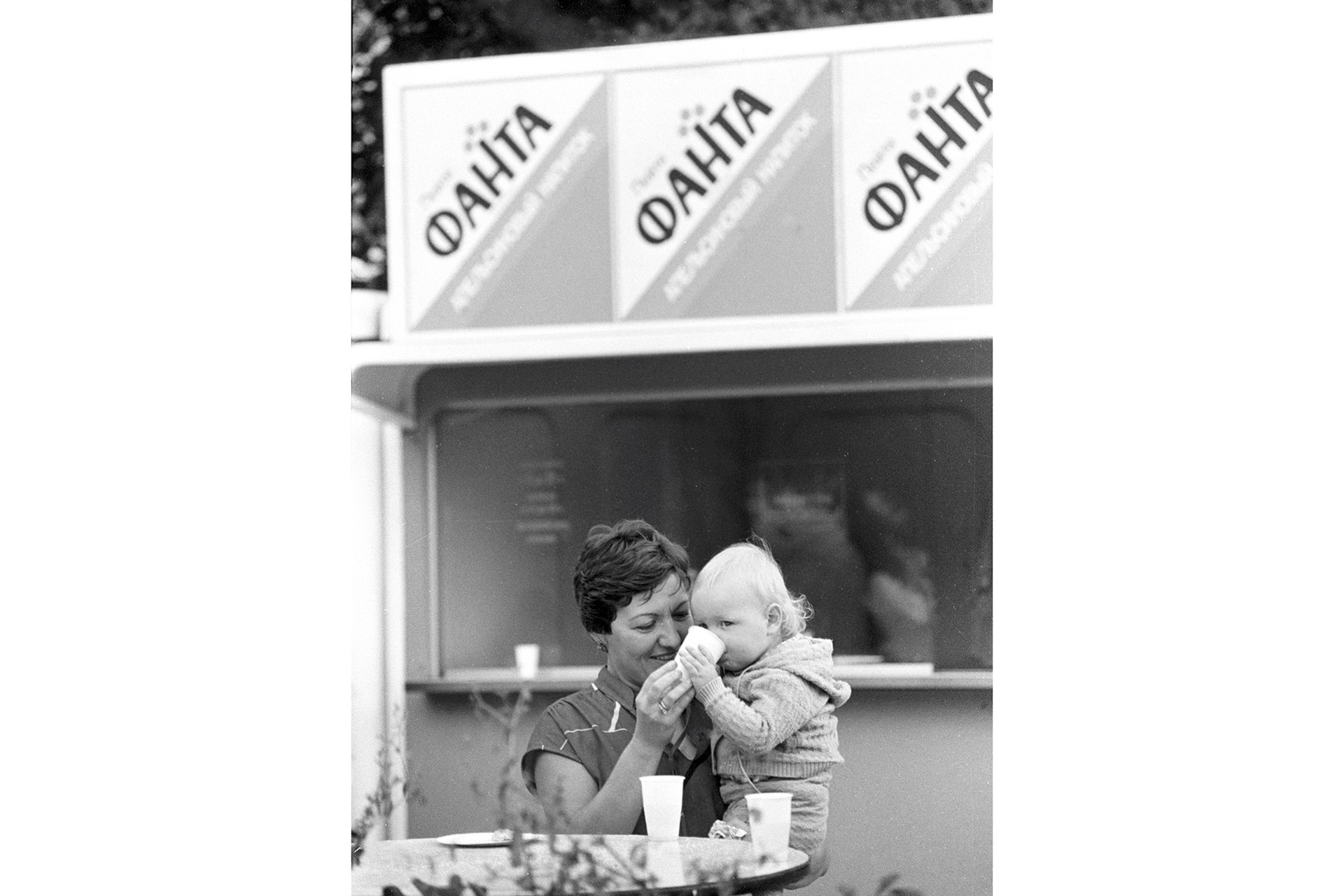

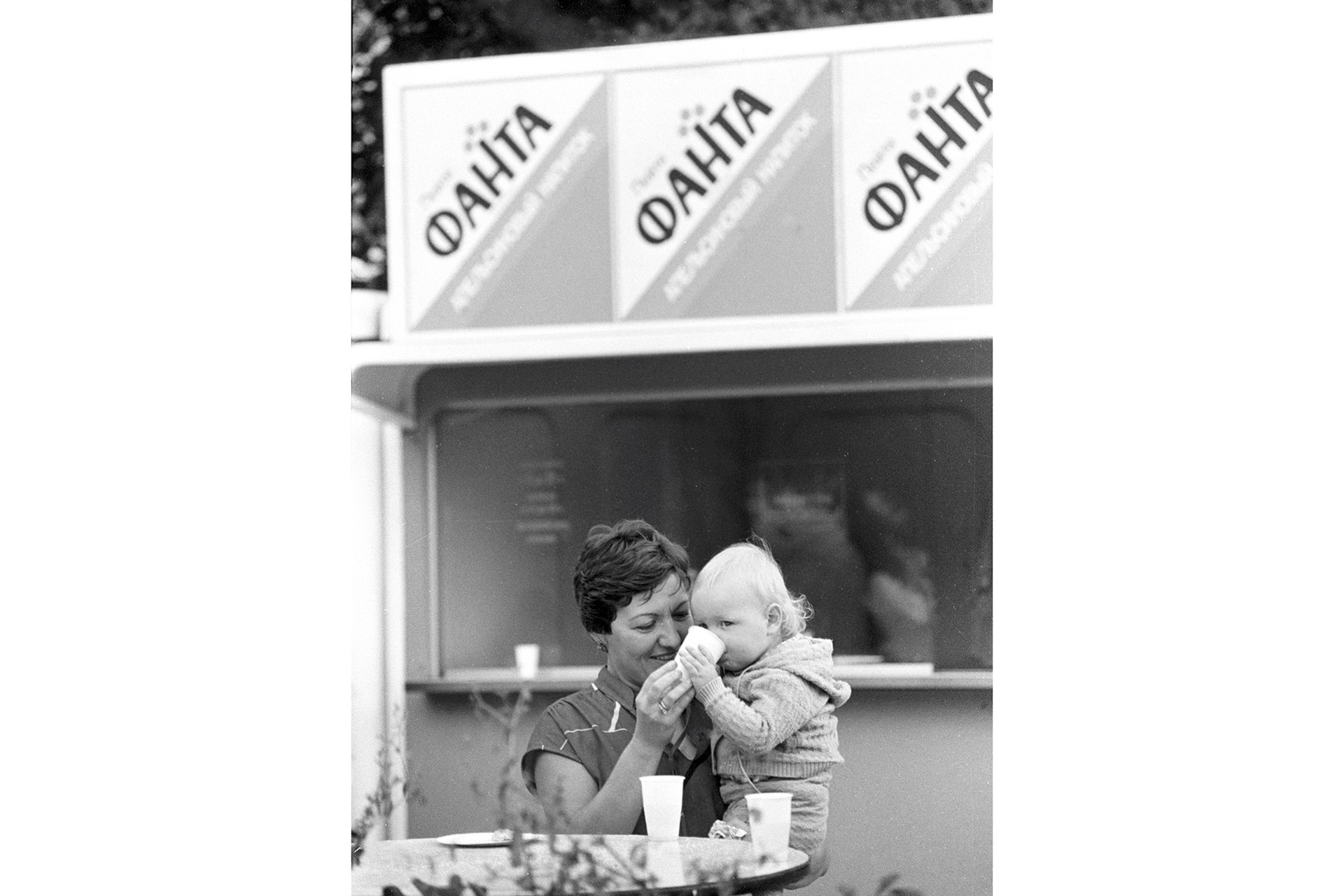

Coca-Cola bosses were horrified to see Pepsi become the first American brand to take root in the Soviet Union and jealous that the massive, potentially lucrative Soviet market was eluding them. Coca-Cola CEO J. Paul Austin parlayed his friendship with U.S. President Jimmy Carter to get direct access to Soviet leaders. As a result of their talks Coca-Cola finally came to the USSR. In 1979, limited quantities of fizzy orange drink, Fanta, appeared in Moscow, Kiev and Tallinn.

Vladimir Fedorenko/Sputnik

The Moscow Olympics of 1980 presented Coca-Cola with a golden opportunity. Although the U.S. declared a boycott of the games following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Coke ignored it, pointing to the fact that it had been sponsor and partner of the Olympics since 1928. As a multinational company it was above politics, it added. Thus Coca-Cola became the main drink of the Moscow Games.

In 1986, Coca-Cola production finally began in the Soviet Union. Lada cars were swapped for the concentrate. It wasn’t a profitable agreement, since it took three days to reconstruct each car before putting it on the European market. Coca-Cola bosses saw it as a loss leader and a way into the Soviet market, where they could take on their arch-rival Pepsi - and perhaps one day eject it.

Vladimir Rodionov/Sputnik

With Coca-Cola's entrance into the Soviet market in the late 1980s, the struggle of the fizzy drinks behemoths heated up. PepsiCo was the first foreign corporation to start advertising on Soviet TV, with spots featuring Michael Jackson. Coca-Cola became the first foreign company to place an advertising banner on the roof of a downtown Moscow building.

In 1989, PepsiCo and the Soviet government signed an incredible barter deal, swapping concentrate for 17 decommissioned submarines and three warships, which the company sold for scrap.

“We’re disarming the Soviet Union faster than you are,” Kendall quipped to Brent Scowcroft, President George H.W. Bush’s national security adviser.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the two soda giants found themselves in a new world: instead of one closed Soviet market, they inherited a dozen new ones in former Soviet republics. The two corporations began a new battle to win the hearts and cash of potential customers.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.