In its dying days, according to various sources, Tsarist Russia counted around 40,000 mansions and dozens of palaces. Many owners fled the Bolshevik Revolution, leaving their homes to ruin and the whims of the lower classes. Only a tenth of these estates have been preserved to this day, while many stand abandoned or destroyed. The situation with the palaces is slightly better, but they too had a tough time during the Soviet years.

The Bolsheviks spared many of St. Petersburg’s palaces and royal residences. Already by 1918, the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoe Selo, the palace-and-park ensemble at Peterhof, and the Gatchina Palace had become museums.

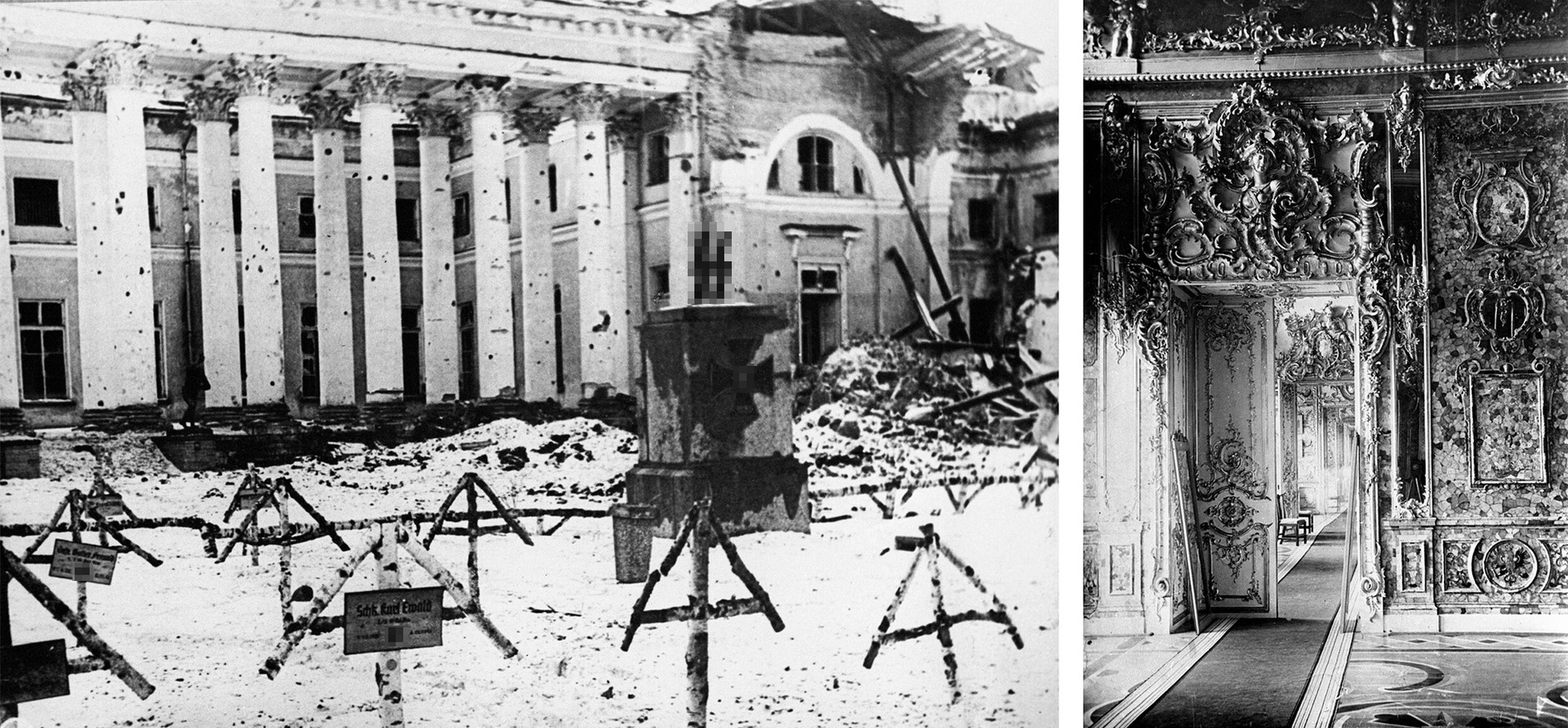

(L) The Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, near Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) after the liberation of the town by the Soviet troops; (R) The Amber Room of Catherine Palace before World War II

Vsevolod Tarasevich/Dmitriev/SputnikFate would play a cruel joke on these manors a few years later. Located outside the city proper, they were all occupied by German troops during WWII. When they were finally driven out, the Germans destroyed and partially blew up many of the buildings and laid waste to the parks (even the famous Amber Room at Tsarskoe Selo was disassembled and removed). The Soviet state carefully restored all the buildings at its own expense; in some cases, for example, at Gatchina, restoration work is still ongoing.

Gatchina palace near St. Petersburg, modern view and in 1944

Russlan Shamukov/TASSThe fate of the Winter Palace was less severe. Having recovered from the shock of the Revolution, it opened as a museum in 1920.

Winter Palace in St. Petersburg

Global Look Press, SputnikMany estates near Moscow were also lucky enough to be converted into museums, including Ostafyevo, Abramtsevo, and Kuskovo. During WWII, however, the latter doubled up as barracks for trainee snipers.

L-R: Abramtsevo, Dubrovitsy, Kuskovo estates in Moscow

Global Look PressThe picturesque Arkhangelskoe also became a museum, but had to make room for a huge military sanatorium built inside the manor grounds.

Arkhangelskoe museum-estate in Moscow

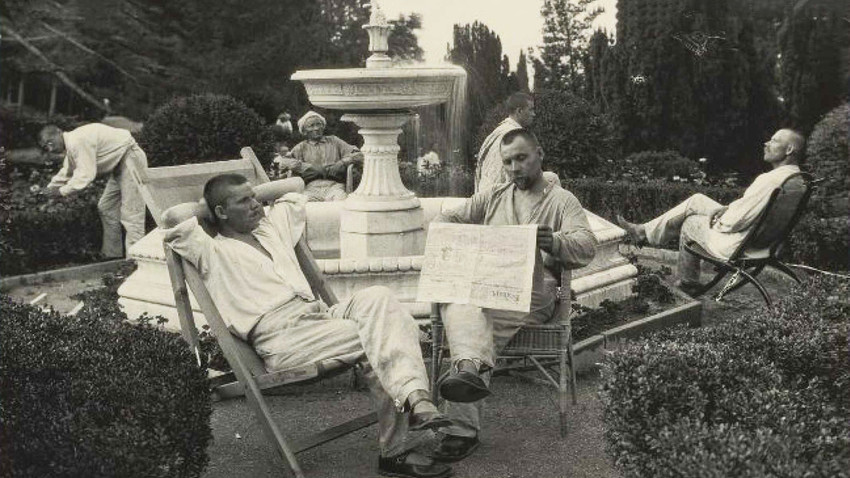

Valery Sharifulin/TASSThis was perhaps the most common use for former estates. The manors of Moscow and nearby suburbs (Uzkoye, Valuevo, Voronovo) still function as sanatoriums, with some being assigned to various government agencies as health resorts.

Valuevo estate in Moscow

Global Look PressUnder Stalin and subsequent leaders, newly built sanatoriums and pioneer camps began to imitate the classical style – with a portico and columns at the entrance, and long enfilades of corridors and chambers. A striking example is the Metallurg sanatorium in Sochi. Constructed in 1956, it could have been the summer residence of a pre-revolutionary count.

Livadia Palace in Crimea

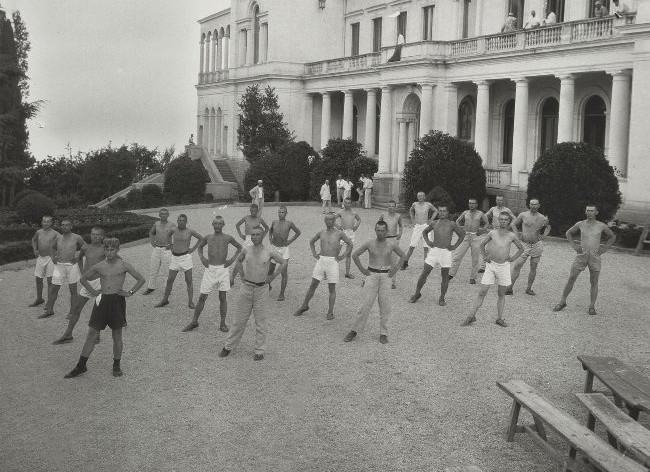

Arkady Shajhet/MAMM/russiainphoto.ruThe luxurious Livadia Palace in Crimea was the dacha of the Imperial family, while in Soviet times it gained fame as the venue of the Yalta Conference between Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill.

Vorontsov Palace in Crimea

Ettinger/SputnikVorontsov Palace, also in the Crimea, became a museum post-revolution. Later, however, this architectural treat on the Black Sea coast was turned into a state-owned dacha. Incidentally, this was where Winston Churchill stayed during the aforementioned Yalta Conference.

Massandra Palace in Crimea

Maks Vetrov/SputnikMassandra Palace in Crimea’s wine-producing region operated as a tuberculosis sanatorium until WWII, before housing the Magarach Institute of Viticulture and Winemaking. In any case, the palace served as yet another dacha for Stalin and later general secretaries.

Lefortovo Palace in Moscow

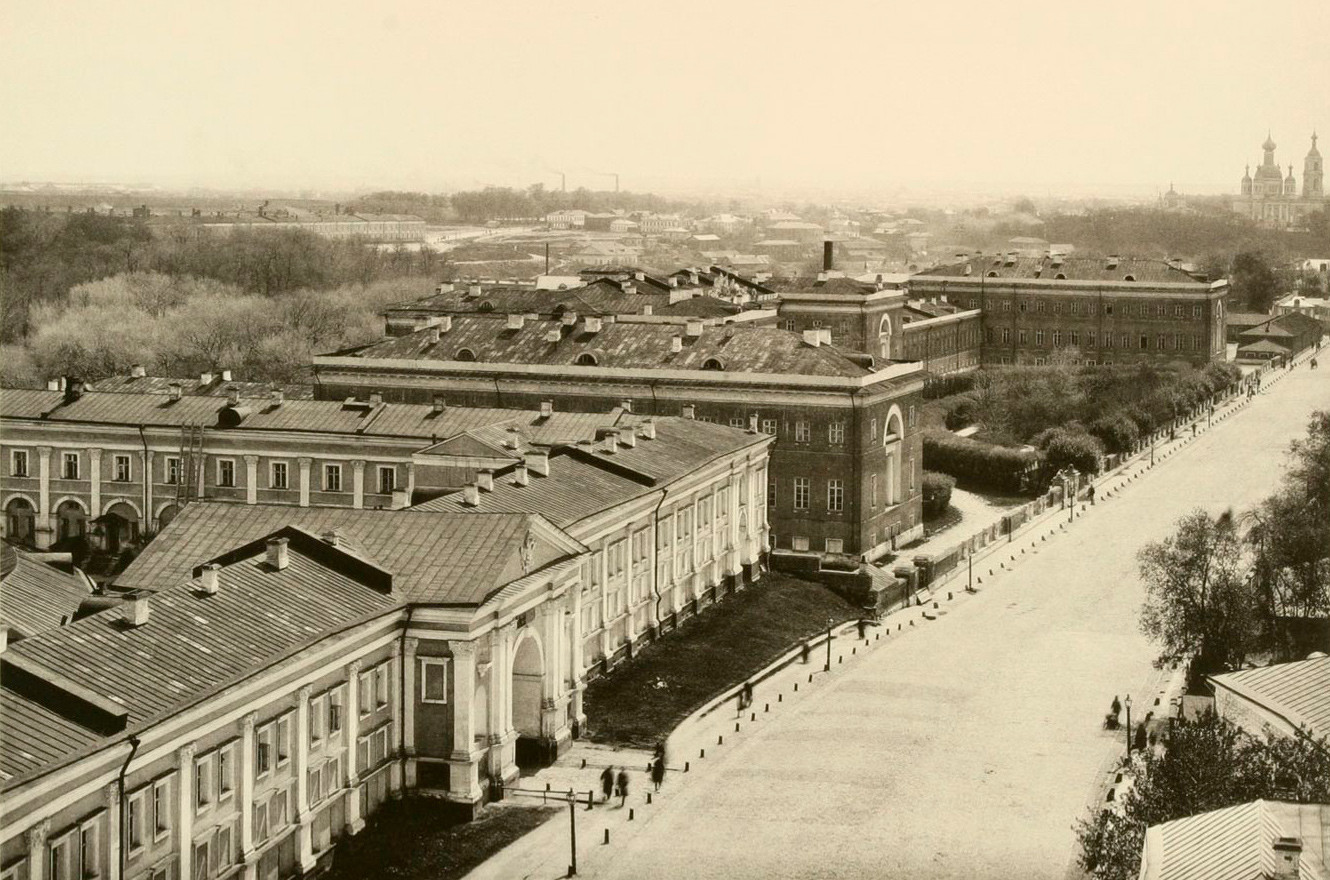

Creative CommonsBack in the 19th century, Peter the Great’s Lefortovo Palace was equipped with barracks, but in Soviet times it was converted into a state military historical archive, which it remains to this day.

The stopover palace in Tver

DmitrySimonov/WikipediaUnder Catherine the Great, several small palaces were built along the road from St Petersburg to Moscow as convenient and comfortable “motels.” After the Revolution, the stopover palaces in Tver and Veliky Novgorod were given to local councils, with the latter eventually becoming a Red Army house of culture.

The stopover palace in Torzhok

Creative CommonsAnother of Catherine the Great’s stopover palaces in the town of Torzhok near Tver was bought back in the 19th century for municipal needs; over the years it has been home to various schools and training centers.

The stopover palace in Strelna

Lidiya Vasilieva/WikipediaIn the late 1980s, the stopover palace of Peter the Great at Strelna became part of the Peterhof museum complex. It too suffered from German occupation, after which it long stood empty and later functioned as a children’s nursery.

The palace of the Golitsyn princes at Vyazemy

Wetscherinin/WikipediaThe splendid palace of the Golitsyn princes at Vyazemy is where Russia’s national poet Alexander Pushkin often spent time in childhood and, legend has it, General Kutuzov spent the night just a couple of days before Napoleon did likewise. In Soviet times, it was multipurpose: a homeless shelter and a school for parachutists and tank crews (due to its proximity to the Kubinka tank garrisons). During perestroika, it became a museum.

The Petrovsky stopover palace

Gennady Grachev/WikipediaThe Petrovsky stopover palace on the approach to Moscow (today the area around Dynamo subway station) was built for Catherine the Great, but she stayed there only twice. After the Revolution, it successively housed a sickbay, a police department, and various People’s Commissariats (Ministries), while in 1923 the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy was established there. During WWII, the renamed Palace of Red Aviation was the base of the Soviet flight command.

Today, the palace belongs to the city authorities and is used to host official receptions. On the first floor there is a museum, while the outbuildings are given over to the boutique hotel Petroff Palace. A night in a room that saw both Russian tsars and Soviet soldiers costs from 8,100 rubles ($124).

Bastion of Paul I

Reklamade/WikipediaIn St Petersburg, an unusual hotel is situated inside the Bastion of Paul I, the eye-catching fortress of the young heir to the throne. During the Russian Civil War, General Yudenich’s White Army HQ was located there. Later, the fortress was used for various needs, including as an orphanage, warehouses, a recruiting station, and even a bank. But during WWII, it was completely burned down, only the stone walls remained. These were restored only in the 2000s.

READ MORE: How did the Soviets use captured churches?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox