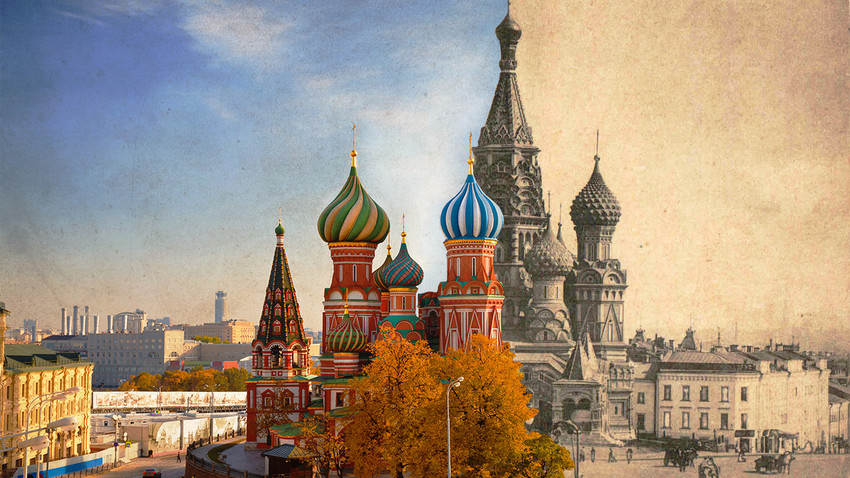

Do you still think the Red Square is called so because its buildings are red? Well, sorry to disappoint you! Even the theory about it being called “red” (‘krasnaya’ in Russian) because it supposedly was a derivative of “beautiful” (‘krasivaya’) in old Russian is wrong.

"The Red Square during Ivan the Terrible's reign" by Appolinary Vasnetsov. The St. Basil's Cathedral is under construction.

Appolinary VasnetsovMoscow’s fortress, later named the Kremlin, was founded on Borovitsky hill. To the East of it, where the Red Square is situated now, there was a huge meadow. As the fortress and the town became more prominent and rich, a posad - or settlement - formed near the fortress walls.

People of the posad lived here because, in case of war, they could hide behind the fortress walls. But the posad needed a market square. Close to the Kremlin and to the Moskva river (which made the transportation of goods easier), the would-be Red Square first began as a market and was accordingly called: torg, or ‘market’ in Russian.

The square has existed since at least 1434. Historians debate whether it was at some point “created” or it just naturally became a market and forum spot. There are grounds, however, to believe that it was the latter case, and here’s why:

Pozhar, ‘the conflagration’, was another common name for the place. Why? It wasn’t because the square often burned. Before the 16th-17th centuries, it contained mostly benches and tents for sellers and no large buildings that could ‘burn’. Pozhar meant not only fire but also a vacant lot that’s usually left after a fire; also, it could have meant the constant buzzing and hustle of the busy market square.

Alevizov moat and Nikolskaya tower.

Fyodor AlekseevBy the beginning of the 16th century, the square had become the main place for news, gossip, and politics in Moscow. If anyone wanted to know what was going on in town, they went here. In 1508, a major innovation was introduced to the Red Square – the Alevizov Moat, created by Aloisio the New, an Italian architect commissioned by Ivan the Third to do work in Moscow. It was over 30 meters wide, 206 meters long and 12-13 meters deep. The moat turned the Kremlin into an island, with Neglinnaya and Moskva rivers defending the remaining sides of the triangle the Kremlin fortress forms.

"The Red Square in the second half of the 17th century" by Appolinary Vasnetsov.

Appolinary VasnetsovA part of the moat (near the Voskresensky gate) later became an animal pit. Here, the Tsar kept tigers and lions presented to him as gifts from Eastern kings. Near the moat, an enclosure for the Tsar’s elephant also existed!

READ MORE: The elephants that entertained Russian Tsars

In 1561, St. Basil’s Cathedral was erected on the Red Square to commemorate the victory of Moscow over the Kazan Khanate. The cathedral has since then dominated the architectural composition of the square and became its main symbol.

The Palace of Facets with the Red Porch

Ludvig14/WikipediaThe name “Red Square” appears in the middle of the 17th century in civil documents during the reign of Tsar Alexis of Russia, Peter the Great’s father. In 1658, he had ordered some Moscow streets and squares to be named differently. But in 1659, the square was still referred to as pozhar in official documents. Only in 1661, did “Red Square” start prevailing.

It’s believed that this name comes from the Red Porch, a staircase that leads to the Palace of Facets, the main reception and banquet hall of the Muscovite Tsars. Red was the traditional color of the tsar’s power, red walls were in his chambers, and the Red Porch was the place where the tsar’s orders were announced to the people. The Tsar would emerge from the Red Porch at major public and religious events. So the square this porch was facing also became to be known as “Red.”

Voskresensky gate before the Revolution

Public domainMeanwhile, the square was still a giant marketplace, divided into many retail rows: everything from pies, honey, clothes, metalware, crockery, meat was sold there! But the trouble was that with a growing amount of shops and tents, fires became more frequent - and more violent. In the 1640s, the first stone Gostinyi Dvor (Merchants’ Court) was erected. Less prone to fire, it became a place for storing goods and selling them. By the end of the 17th century, there were no more wooden buildings left on the Red Square. The square also received a beautiful entrance from the North – the Voskresensky Gates. In 1698, Peter the Great finally banned all stationary trade from the square.

Tram line on the Red Square

Public domainThe Red Square remained the center of Moscow’s political life. Lobnoe mesto, a stone postament near St. Basil’s Cathedral, was the place where the government's most important orders were announced. Executions of the most notorious criminals were also performed around this spot on Red Square. Not much changed until the beginning of the 19th century, when the Alevizov moat was filled, the square was paved with cobblestones and new wooden trading stalls were built.

The State Historical Museum is seen in the background

Legion MediaIn 1875, the obsolete buildings near the Voskresensky gate were demolished to build a new State Historical Museum (1875-1883). The imposing red building in pseudo-Russian architectural style matched well with the Kremlin walls and St. Basil’s Cathedral and served as the “fourth wall” for the Red Square, finally making it a rectangle.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Red Square had electric lighting, a new GUM department store and a tram line going across it. When the Bolsheviks came to power, they demolished the Voskresensky gate in order to make way for tanks during military parades, built Lenin’s Mausoleum and organized a cemetery for the Soviet elite - right where the Alevizov moat once was.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox