Fantômas conquered the USSR in months and sort of became more popular than Leonid Brezhnev himself.

André Hunebelle/GaumontPicture yourself as a 7-12-year-old kid in late-1960s USSR. Leonid Brezhnev is in charge and there are two decades of zastoi (stagnation) era ahead of you. The school bombards you with Russian classics, while the TV does the same with speeches on how communism will make your life happier and crush all those Western scoundrels who dare oppose your glorious country.

Movies are quite dull as well – at least for your age. As great as it is (you already have Andrei Tarkovsky), Soviet cinematography certainly lacks the entertainment power of movies one can consume popcorn and cola to (not that you’ve got those either). You would certainly be depressed had you known there is an alternative – but the iron curtain is solid, and nothing seeps through from the West.

All of a sudden, you see an action movie that has everything you could even dream of: shootouts, car chases, murder – and a fantastic cast. To you, a small 1960s child, it’s like Avengers: Endgame, Game of Thrones and whatever other contemporary blockbusters you could imagine all molded into one. You keep rewatching it again and again. The movie in question is French, it is called Fantômas. And its creators could never have expected it to achieve such success.

The first reincarnation of the villain appeared in books (one of its first covers).

Creative CommonsOriginally, the character of Fantômas, the shape-shifting evil genius, first appeared in the 1900s, created by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre - two French pulp fiction writers. Before Souvestre died in 1914, they wrote more than 40 books – most of them grim, and depicting horrendous murder scenes. There were several successful screenings – but the 1964 one beat them all.

Director André Hunebelle rebooted the Fantômas universe so radically that even J. J. Abrams with his new Star Wars trilogy can’t be compared. Hunebelle dropped all the detective stuff the previous Fantômas movies clung to and turned the noir story into a comedy mocking James Bond movies.

Inspector Juve played by Louis de Funès.

André Hunebelle/GaumontIn Fantômas, the police inspector Juve, who is after Fantômas, is played by the comedian Louis de Funès, and portrayed as a total fool (though a very charming one). But it was the villain embodied by famous Jean Marais, who totally stole the show – even though his green rubber mask may look incredibly stupid nowadays.

Hunebelle made three films about Fantômas and his pursuers (the plot, generally, goes as follows: they try to catch Fantômas, he tries to kill them, everyone fails), they were quite a success all over Europe. But things got real only when France sold copies of the movie to the USSR in 1966.

Fantômas was famous for his evil laugh - even though it appeared only in the Soviet version.

André Hunebelle/Gaumont“In total, more than 120 million people in the USSR watched the Fantômas movies,” Rossiyskaya Gazeta wrote: quite a lot for the Soviet box-office. Viktor Dragunsky, a children's author, summed up the reason the elusive villain had become a hit with the public in his short story, Fantômas, as told through the eyes of a Soviet child:

“Wow! That’s some movie! You can go crazy after seeing it, I promise you. You know, when you’re watching our movies, there is no amusement there: just a thief coming to the police crying and turning himself in, telling all about his hard life and him stealing two fire hoses from a local fire department. This goes on for two hours, what can you do. But Fantômas is different! You have mystery, you have masks, you have adventures and fights! So, all the boys immediately started play-acting Fantômas.”

They had – and not in a good way. Several months after the movie premiered, multiple minor offenses flooded the USSR. Teens and children who attacked paper or tobacco shops, broke shop fronts or burned mailboxes were leaving notes, reading “Fantômas did it!” They had been calling random phone numbers using ominous voices: “Fantômas will come for you in several minutes!” and leaving notes. One mentally unstable person even started several fires.

Eventually, a real gang of “Fantômases” appeared in the USSR. Actually, they had nothing to do with Hunebelle’s trilogy – those people were adults and probably never saw the French movies. However, they committed their crimes wearing stockings on their heads, reminiscent of the villain’s rubber mask.

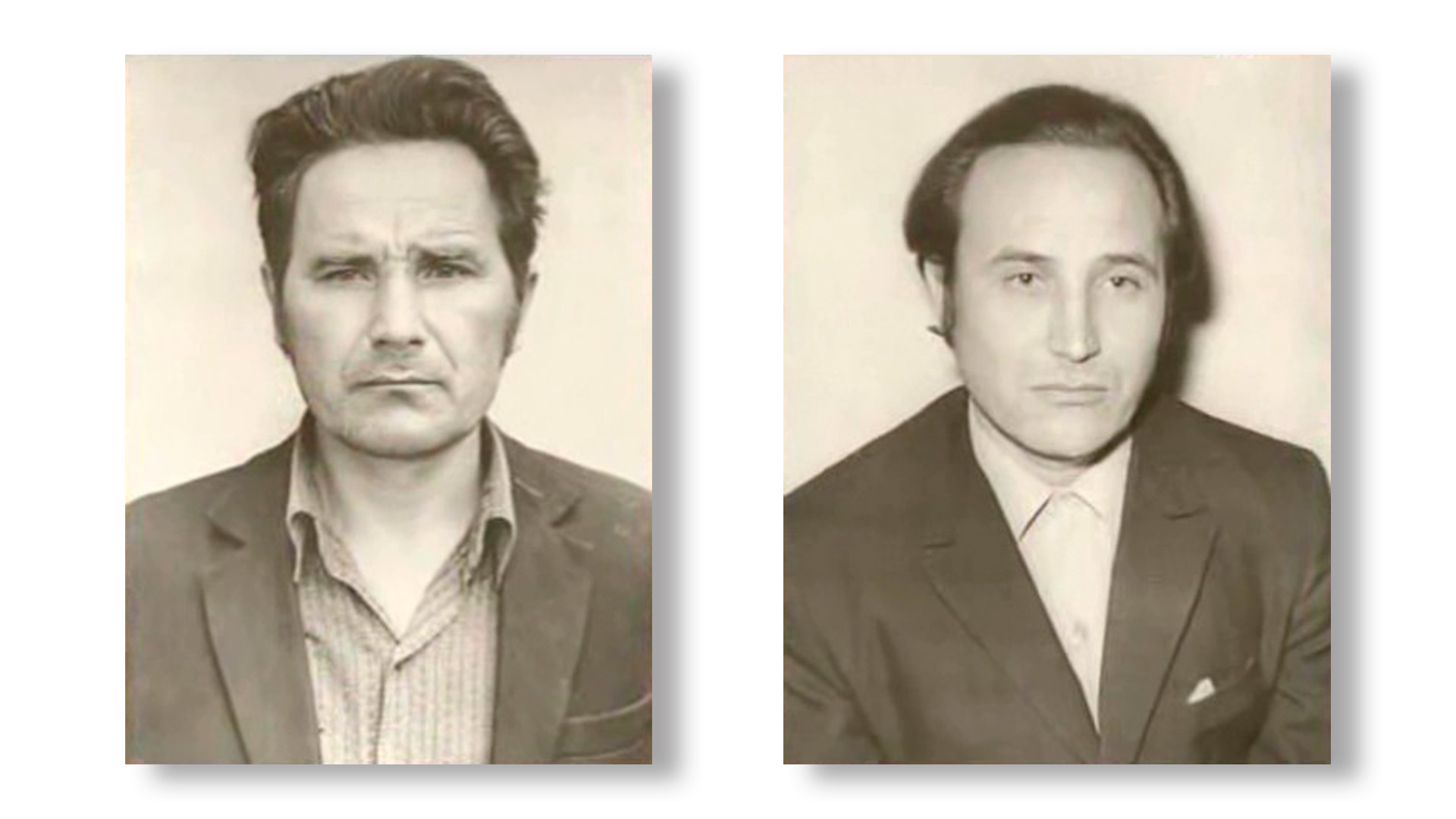

Brothers Vyacheslav and Vladimir Tolstopyatov had formed the gang in 1968 in Rostov-on-Don (a southern city close to Ukraine). “For five years, stunning rumors about them circulated the city,” wrote prosecutor Nikolay Buslenko. “It wasn’t surprising – many people witnessed armed robbers in rubber masks attacking banks. That’s why they were called Fantômases. Word had spread of them… so the city was close to panic.”

Vladimir and Vyacheslav Tolstopyatov.

NTV TV channelFor a while, the Tolstopyatov gang was as elusive as the fictional villain: they robbed shops and banks, and got away – though the sums were not that big, Buslenko writes. They were using home-made guns - including automatic ones - as it was impossible for civilians to acquire weapons in the USSR. And it got brutal: “Fantômases” ended up killing three people who tried to confront them.

The state system was merciless as well, though: in 1973, the police finally caught the “Fantômases”, killing one of four gang members in detention. Three others were sentenced to death. As for their prototype of the villain, in the 1970s his fame slowly faded and was replaced with new heroes and bad guys.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox