When the Allies liberated the German concentration camps, they were shocked by what they saw: the prisoners could barely stood on their atrophied legs. Skinny, exhausted by hunger, thirst and sicknesses, they literally were on the verge of death.

Some of these liberated prisoners not only survived and returned to normal life, but did the near impossible. Just several years after the horrors of the camps, they entered the sporting arena and beat the world’s strongest athletes at the 1952 Olympic Games.

Ivan Udodov

Anatoly Garanin/SputnikIvan Udodov was only 17 when the Germans sent him to the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1941. When four years later he finally left it, he weighed only 29 kg and couldn’t walk without assistance.

To start with, sport was a part of the rehabilitation process recommended by his doctors. But soon weightlifting became his life’s passion.

Udodov worked hard and results soon came. Already in 1948 he won second place at the Soviet Southern Championship, and in 1951 became the champion of the Soviet Union in the lightest category (up to 56 kg). Then he was invited onto the national team.

The Olympic Games in Helsinki in 1952 were the first ever Olympics for the Soviet Union, and it was Udodov who won the country its first gold. Surprisingly for the whole sporting world, he beat the Iranian favourite Mahmoud Namjoo.

Soviet weightlifter Arkady Vorobyov recalled: “We were a team of war veterans. It will take time for the post-war youth to become strong. And while its time has not yet come, those who experienced hunger, cold, wounds, exhausting work in the rear and the nightmares of the concentration camps were the ones who stepped up to the starting line. And still we were very optimistic. It wasn’t 1946 or even 1950. Our strength had increased. We could take Olympic gold. We believed that our sporting bravery would be no less than our military courage. Ivan Udodov was the first one to win a gold medal. And his success was much more than a sporting victory…”

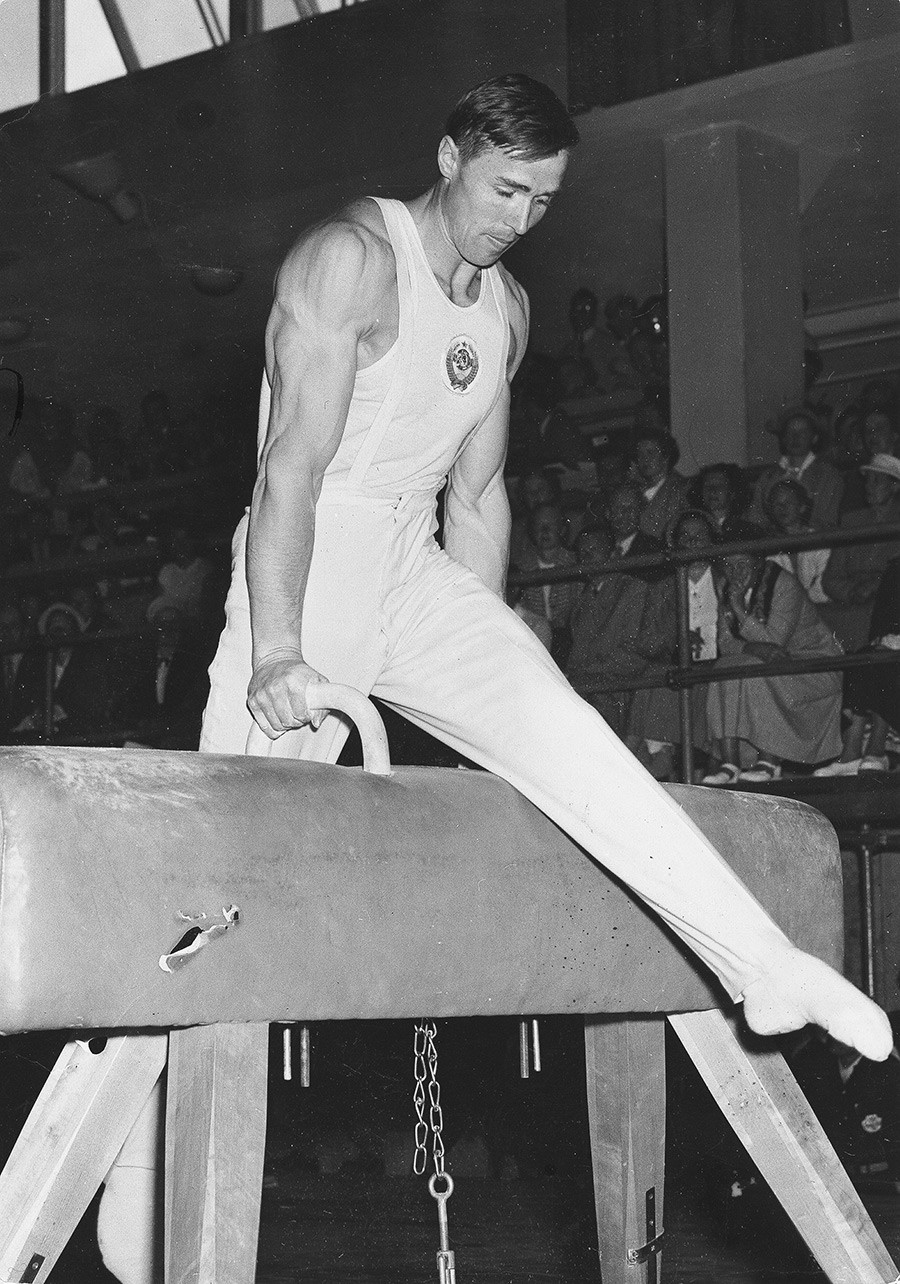

Viktor Chukarin

Getty ImagesUnlike Udodov, Viktor Chukarin started to practice professional sport before WWII. Already at the age of 19 he became a champion of Ukraine in gymnastics. But the war radically altered the plans of this fine young talent.

Chukarin enlisted as a volunteer, was wounded and taken into captivity. He went through 17 prison-of-war camps. In 1945, along with other prisoners he was condemned by the Nazis to be drowned on the “barge of death” in the open sea, but was saved by the British.

When Viktor returned home, he weighed only 40 kg. His mother recognized him only by the scar on his head.

After rehabilitation, Chukarin started to make up for lost time. As early as 1946 he was one of the Top 20 sportsmen in the Soviet Union, and in 1948 won the national gymnastics championship. The next step was the 1952 Olympics.

In Helsinki, 31-year-old Viktor Chukarin had to compete with much younger sportsmen, but this was no obstacle to triumph. He won four gold and two silver medals, becoming the most successful athlete of the Olympic Games.

Yakov Punkin

Public domainYakov Punkin survived the German prisoner-of-war camps by miracle. A Jew, he was forced to hide his true nationality and pose as a Muslim Ossetian.

Every minute of his life in different forced labor camps across Germany Yakov was afraid that there would be a traitor who might reveal who he really was.

At the end of the war, Punkin weighed 36 kg, weakened by typhus and long hunger. As soon as possible he returned to Greco-Roman wrestling, which he had started to practice already before the war.

His sporting journey was amazing. In 1947 he won the Soviet Army Championship, and ahead of the 1952 Olympics was the three-time Champion of the Soviet Union.

In Helsinki, Yakov Punkin was known as “lightning on the mat.” He won the gold medal in the category up to 62 kg, beating Abdel Aaal Rashed. Before the bout, the Egyptian wrestler proudly said it would take two minutes for him to beat his Soviet opponent. In fact, Yakov defeated him in three minutes.

Yakov’s colleagues much admired his character, praising his iron nerves. “I am never afraid on the mat. I used up my fear quota in the concentration camps,” Punkin used to say.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox