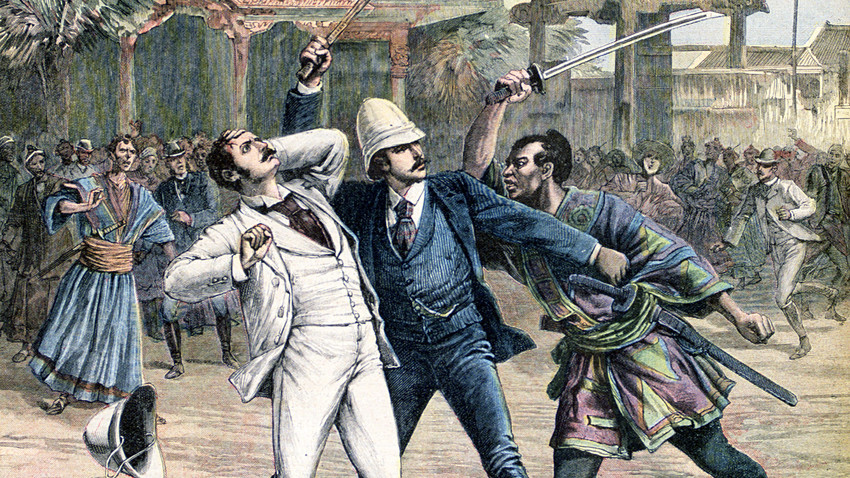

Attempt on the life of Grand Duke Nicholas, by a police officer at Otsu. Attack blocked by Prince George of Greece, a cousin of the Tsarevich. From 'Le Petit Journal', Paris, 30 May 1891

Global Look PressThere is almost nothing physically left of the last Russian czar and his family. After their brutal murder, their bodies have been burned. In 1991, some remains supposedly belonging to the tsar and his family have been discovered near Yekaterinburg. The remains were reinterred in St. Petersburg in 1998, but they still needed proper genetic expertise. But where to find samples of the last Romanovs’ DNA? Actually, there was an item that had royal blood on it: in Hermitage in St. Petersburg, a shirt with Nicholas’s blood on it was preserved. The shirt he had been wearing when a Japanese policeman almost slaughtered the would-be tsar.

The Eastern journey

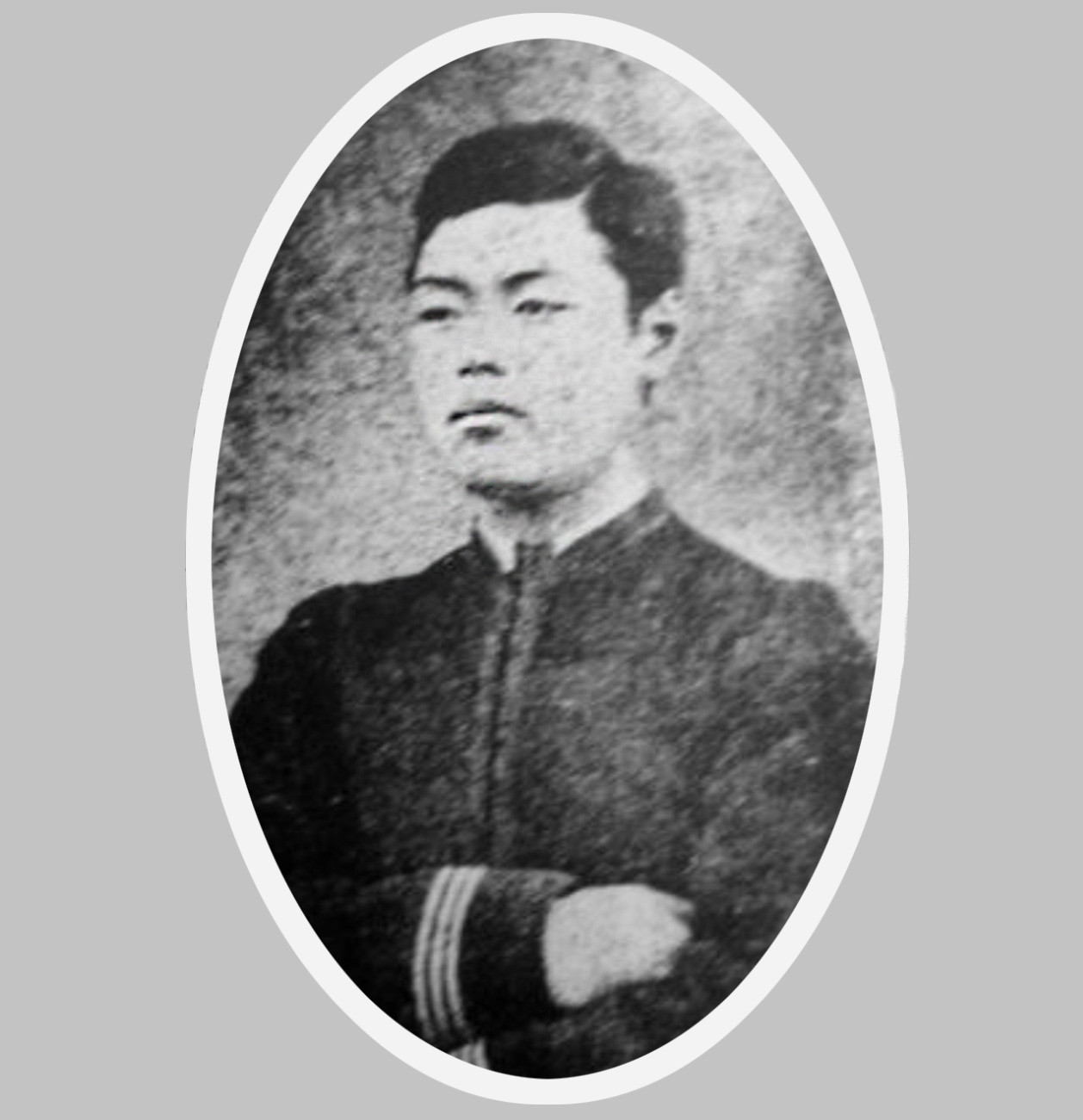

Grand Prince Nicholas Alexandrovich of Russia (future Tsar Nicholas II) at Nagasaki, 1891

Nagasaki City Library ArchivesIt was a tradition for the Russian nobility to travel to foreign countries in one’s youth. In 1890-1891, Grand Duke Nicholas Alexandrovich of Russia, the would-be Nicholas II, went to the East. It was the idea of his father that the heir must visit not Europe (as usual), but the Eastern countries, finishing his journey in Japan. In addition to his suite, Nicholas was accompanied by his distant relative, Prince George of Greece and Denmark.

Japanese admiral Prince Arisugawa Takehito (1862-1913)

Nicholas went to Egypt, India, Singapore, China and then to Japan, where his visit was greatly expected: it was the first-ever visit of an heir to a foreign throne to Japan. An influential Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun wrote that Nicholas’s visit was an even of ‘vital importance’ to Japan. However, the attitude to Russia in Japan was troubled: in November 1890, half a year before Nicholas arrived in Japan, the Russian Embassy was attacked. Upon arrival, Nicholas was greeted at the highest level possible: all the time, he was accompanied by Prince Arisugawa Takehito, a member of the Japanese Imperial family. However, all this didn’t save Nicholas from a horrible incident.

The Ōtsu incident

A street in Otsu where the attack happened

Mendeleev V. D.On Monday morning April 28th, 1891, Prince Nicholas, Prince George, and Prince Arisugawa Takehito went to the old town of Ōtsu for sightseeing. The streets of the old town were very narrow, so instead of horse carriages, the guests were riding in rickshaws. As the procession of about 50 rickshaws carrying Nicholas, his friends and suite, and Japanese officials, was moving through Ōtsu on its way to Kyoto, one of the Japanese policemen,

Tsuda Sanzō, who guarded the procession, suddenly attacked Nicholas with his saber. Nicholas suffered two blows on the head before jumping out of the rickshaw and running for his life. Prince George struck Tsuda with his bamboo cane (in other versions – blocked another blow with it), but couldn’t stop him; at last, the two rickshaws managed to stop Tsuda.

The consequences

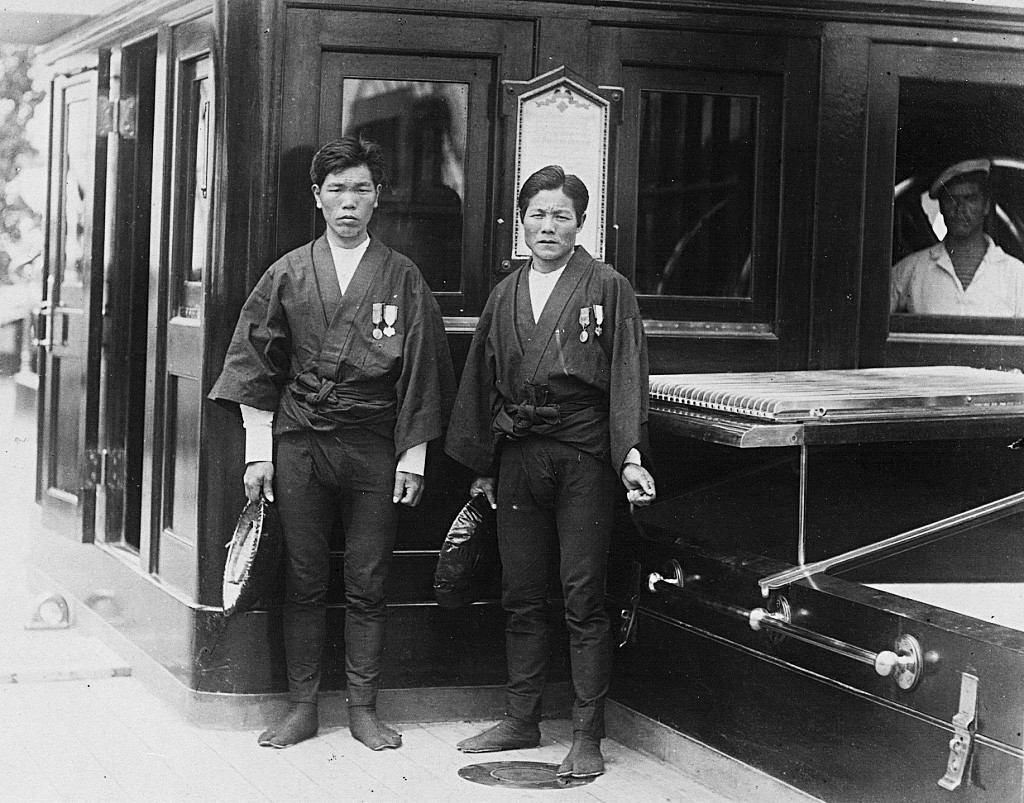

The rickshaw drivers who apprehended Tsuda, Kitagaiichi Ititaro (L) and Mukokhata Dzisaburo (R)

Archive photoImmediately after the incident, Nicholas’s wounds were dressed on the spot. The Grand Duke suffered a 9-centimeter wound to the back of his head, reaching the bone, and a similar 10-centimeter wound to the forehead, and a wounded palm and an ear. A 2,5-centimeter fragment of the forehead bone was removed during the dressing of the wound. However, Grand Prince said that he’s in good condition. “That’s nothing,” he said of the wound. “I’m just hoping that the Japanese wouldn’t think I would change my feelings towards them and be less grateful for their hospitality,” Nicholas said to Prince Arisugawa Takehito. Nicholas was hastily taken to Kobe harbor, where Russian doctors from the Russian cruiser ‘Pamiat Azova’ made stitches on his wound.

The wound, however, became the reason for excruciating headaches that bothered Nicholas for the rest of his life.

Japan after the incident

Gifts from Japanese people to Grand Duke Nicholas on his birthday on the Russian cruiser ‘Pamiat Azova’ on May 6th, 1891

Mendeleev V. D.The Japanese society was awestruck and disgusted with what Tsuda did. In fear that the incident might exacerbate the relations between two countries, Emperor Meiji himself traveled to Kyoto immediately to meet Grand Duke Nicholas. As a gesture of respect for the wounded Russian heir, the next day after the incident theaters, stock exchanges, and public houses were closed.

Emperor Meiji expressed hope that Nicholas would not be offended and would continue his visit to Japan. Meanwhile, in St. Petersburg, Alexander III decided to stop the journey immediately. After Nicholas boarded ‘Pamiat Azova,’ where he was treated, he didn’t leave the ship anymore. On May 6th, Nicholas celebrated his 23rd birthday on board and the next day, he left for Russia. But before leaving, he invited the two rickshaw drivers who stopped Tsuda and awarded them lavishly.

Japanese society grieved after what Tsuda did. About 24 thousand telegrams with condolences were sent to the Russian cruiser where Nicholas was staying. The incident even caused a suicide when a young seamstress, Yuko Hatakeyama, slit her throat with a razor in front of the Kyoto Prefectural Office as an act of public contrition, and soon died in a hospital. Accepting responsibility for the lapse in security, Home Minister Saigō Tsugumichi and Foreign Minister Aoki Shūzō resigned.

Who was Tsuda and what were his goals?

Tsuda Sanzō (1855-1891)

Archive photoIt remained largely unclear why Tsuda Sanzō did what he did. It is believed he considered himself a samurai and was a die-hard patriot who remembered how foreigners were scolded and hated in Japan before the Meiji era. Tsuda was disgusted at all the honor and respect the Japanese paid to foreign guests, and probably angry at Nicholas who didn’t take his shoes off while visiting a Buddhist temple. In addition, he suspected Nicholas and George of Greece to be foreign spies preparing an invasion to Japan. All this simultaneously obscured Tsuda’s mind and made him attack Nicholas.

The Japanese court gave Tsuda a lifetime of hard labor; the Russian government expressed full satisfaction at this decision. But in September the same year, Tsuda died in confinement. It is rumored that he starved himself to death.

Although later in his diary Nicholas wrote that he wasn’t angry with Japanese after “a disgusting thing done by a zealot,” his ministers noted that he treated Japanese rather warily. The Ōtsu incident has often been mentioned in connection to the Russian-Japanese war of 1904-1905 – some historians think that it was easier for Nicholas to give consent for this war, taking into account his attitude towards the Japanese after the incident.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox