How Soviet girl Katya Lycheva met Reagan and helped end the Cold War

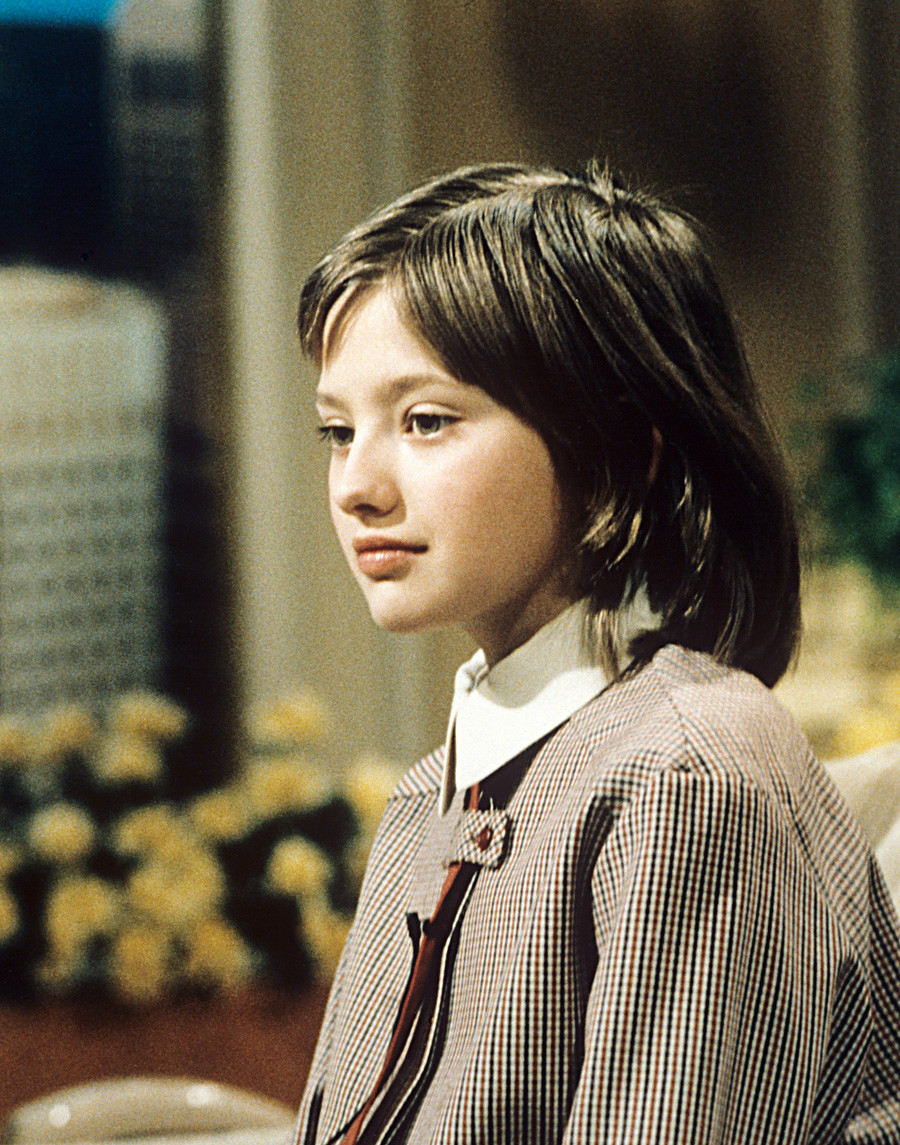

11-year-old Katya Lycheva was chosen to be a Soviet Goodwill Ambassador to the U.S.

Viktor Velikzhanin and Valentin Kuzmin/TASSIn the 1980s, relations between the USSR and the US were at near breaking point. The arms race was peaking, Europe was a stationing ground for hundreds of nuclear missiles pointing in either direction, and US President Ronald Reagan openly described the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” It seemed that full-scale war was a heartbeat away.

It was then that 10-year-old American Samantha Smith helped break the ice between Moscow and Washington. In a heartfelt letter to General Secretary Yuri Andropov, she asked: “Are you going to vote to have a war or not?” The world sat up and took note. Andropov answered Samantha, assuring her that no one in the USSR wanted war, and invited her to visit the country. She accepted the offer, and the whole world followed her journey across the USSR with her parents. Along the way, Samantha understood that the USSR was full of kind, peaceful people, and she made many new friends. Her youthful idealism became a symbol of hope for a better future for all.

Tragically, in 1985, just two years after her trip, Samantha was killed in a plane crash. Soon, however, another girl assumed the mantle of “global peace ambassador” – Katya Lycheva from the Soviet Union. In her homeland, however, she was far less loved than Samantha.

Why the USSR didn't embrace Katya

New York, USA. Soviet school girl Katya Lycheva during her visit to the USA as a Soviet Goodwill Ambassador.

TASSWhen Katya was first sent to the US in 1986, rumors circulated that “she was a relative of Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, and could not even speak English. A lot of dirt was poured over Katya. It's completely unjustified in my view,” says Lyubov Mikhailova, who worked as a TASS journalist in the 1980s.

In fact, the idea for Katya’s trip came from the Americans, not the Soviets. After the death of Samantha Smith and her father in a plane crash, her mother Jane and the Children as Peacemakers organization, which she founded, suggested that the USSR arrange for a Soviet schoolgirl to visit the U.S. in continuation of Samantha’s mission.

Katya Lycheva (L) and her new American friend Star Rowe during Katya's visit.

TASSThe Soviet Union agreed, and promptly held “auditions” – attended by around 6,000 hopefuls. The chosen one was Katya Lycheva. It is now known for sure that she did not have family inside the Communist Party. Her parents were academics, and she studied at a special English school in Moscow. What’s more, she had quite a bit of acting experience, having appeared in three films. The girl’s appearance was also important. With her fair curls and blue eyes, Katya was sure to be liked by the American public.

Katya meets Ronald

Katya Lycheva together with actors of Broadway theatre.

Morton BiBi/SputnikDuring Katya’s trip to the US, her diary notes were serialized in the Soviet media, and later published in the collected volume Katya Lycheva Tells. In it, she describes meeting the US president:

“After five minutes, Mr. Reagan appeared, stretched out his hand, and said he was very pleased to see me in the White House. I gave him a toy and explained it had been made by Soviet children, who, like all of our people, want peace. Mr. Reagan replied that although he was no longer a child, he too dreamed of peace, and promised me that he would do everything to ensure there were no nuclear weapons left on Earth. He wished my mother and me a good time in America, and said he envied us because we’d been to the circus the day before, while he didn’t time to go there.”

Katya meets the other Ronald

Katya at McDonald's.

TASSWhen Katya went to McDonald’s for the first time, the press coverage reached fever pitch. The sight of a Soviet girl feasting on a Big Mac and fries in America caused no less a sensation than her meeting with Reagan.

“We had lunch that day at McDonald’s. I’d already heard it was a well-known chain of small restaurants. At the entrance, we were met by a smiling clown in a huge red wig. I immediately thought I was back at the circus... But everything there was really tasty. They brought us an appetizing sandwich called a Big Mac and crunchy slices of potato. I wanted to eat the sandwich, but every time I raised it to my mouth, there was such a flash of cameras that it was impossible to tuck in.”

Back in the USSR, no one had a clue what McDonald’s was. It would be another four years after Katya’s trip before the fast-food empire opened its first outlet there. For the first few months of its existence, the McDonald’s restaurant at Pushkinskaya was a kind of pilgrimage site, with endless lines of people snaking around the streets.

Katya floors Rocky

Katya Lycheva and her American friend Star Raw strolling in Moscow.

Igor Mikhalev/SputnikKatya’s impressions from her American adventure were not all positive. Above all, she was shocked by the movie Rocky IV, in which Sylvester Stallone’s title character faces the Soviet machine Drago (played by Dolph Lundgren). She wrote in her notes: “When [Drago] killed [Creed], I ran into the bedroom, threw myself on the bed, and burst into tears. I was hurt by how our country was so falsely and cruelly portrayed...

The next day, I said in a TV interview: “There was not a word that was true in [Rocky IV]. Even the faces of the Soviet people were not the way they really are. I’m ashamed of the adults who made the film.”

Her remarks caused a stir in the US media: “What is objectionable about this film is not the conflict between the characters but the constant and unabashed pressure on the audience to scorn, pity, and demean the Russian people and their government,” wrote Carol Basset of the Chicago Tribune in support of Katya.

Back home

Jane Smith (second on the left), mother of the died U.S. peace envoy Samantha Smith and Katya Licheva (second right) participate in the opening ceremony of I Goodwill Games in Moscow.

Yury Abramochkin/SputnikIn the days and weeks after her trip, Katya was a huge news item in the USSR – everyone wanted to know what America looked like, what people there ate, how they dressed, what they read. She took part in public events, received sackfuls of mail, and had stories and anecdotes told about her. As a result, she had little time for normal life and contact with her peer group.

In the end, Katya and her family decided they’d had enough of the media spotlight. Soon afterward, the name of Katya Lycheva disappeared from Soviet news. She and her mother moved to France, where she studied at the Sorbonne, graduated in economics and law, and worked there for a few years, before returning to Russia in 2000. Today, the grown-up Ekaterina refuses to speak to journalists on principle – the attention she received as a child was more than enough for one lifetime.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox