The Soviets planned to wipe out the U.S. with a huge tsunami. How?

In September 1961, The New York Times reported that the Soviet Union was preparing to test a powerful explosion. The plan was to detonate 100 million tons of strategically placed TNT, causing waves that would devastate the U.S. Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

The project, codenamed Lavina (Avalanche), envisaged the creation of an artificial tsunami as a cleaner alternative to nuclear weapons, yet still ferocious enough to cause massive casualties among the civilian population. It gets even more disturbing when the project leader’s name is mentioned, for it was none other than Andrei Sakharov, the renowned physicist and Nobel Peace Prize winner, widely considered one of the greatest humanists of the 20th century. How can that be?

How to create a catastrophe

The deadly project, which bore more than a passing resemblance to the movie The Day After Tomorrow, was not actually a Russian idea. The first attempts to cause a tsunami were carried out by the Americans themselves. Their top-secret operation Project Seal was essentially identical in purpose: to wipe the enemy off the face of the earth with a superpowerful wave.

It was conceived by naval officer E.A. Gibson, when he noticed how blasting operations to clear the coral reef around the Pacific Islands led to huge waves. Assuming the size of the wave to be directly dependent on the force of the explosion, the military decided to investigate this theory. Tests began in 1944 off the coast of New Caledonia, where 3,700 bombs were detonated, and later near Auckland, New Zealand.

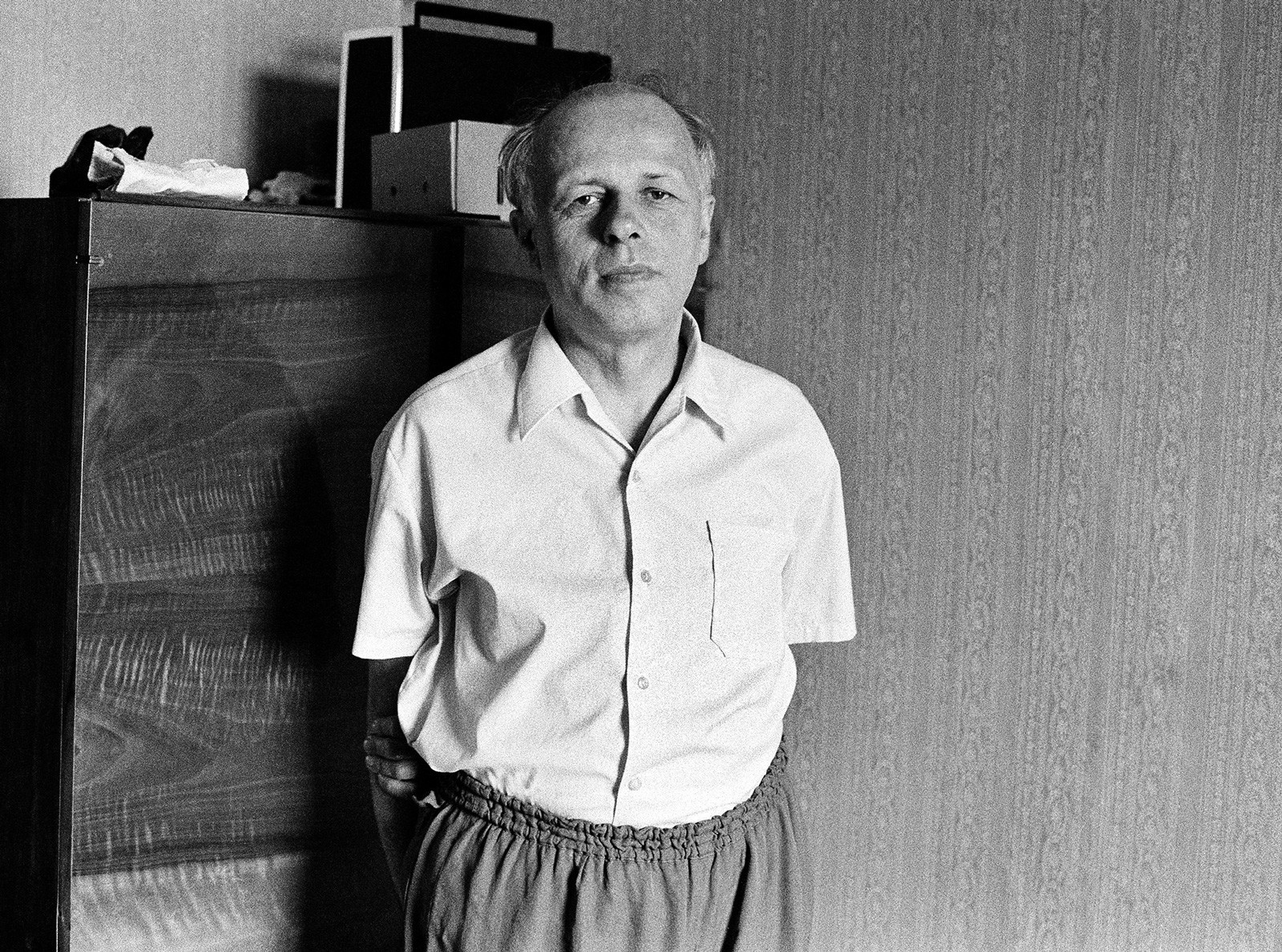

General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev

Sputnik“It was absolutely astonishing. First that anyone would come up with the idea of developing a weapon of mass destruction based on a tsunami ... and also that New Zealand seems to have successfully developed it to the degree that it might have worked,” said New Zealand film-maker Ray Waru, who examined the military files buried in the national archives.

It wasn’t long before the Soviet Union received intelligence reports on the US testing and thought it a great idea – far more effective than aircraft carrying nuclear warheads, which were trackable by air defenses. Then General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev ordered feasibility studies to be carried out.

“I was ashamed”

By that time, the USSR had already developed its own hydrogen bomb, one of the creators of which was physicist Andrei Sakharov. A team of scientists, him included, faced the task of testing the bomb in new conditions – water. The problem was how to deliver it.

In his memoirs, Sakharov later wrote: “After testing [the Tsar Bomb], I was concerned about the lack of means for carrying it (bombers were no good, they could be easily shot down). It meant that in a military sense, our work was futile. I decided that the carrier could be a large submarine-launched torpedo.” A US naval base was earmarked as the strike target. “Sure, the destruction of ports – caused by the above- and underwater explosions as the 100-megaton torpedo ‘jumped’ out of the water – would have resulted in mass casualties,” wrote Sakharov with brutal impassivity.

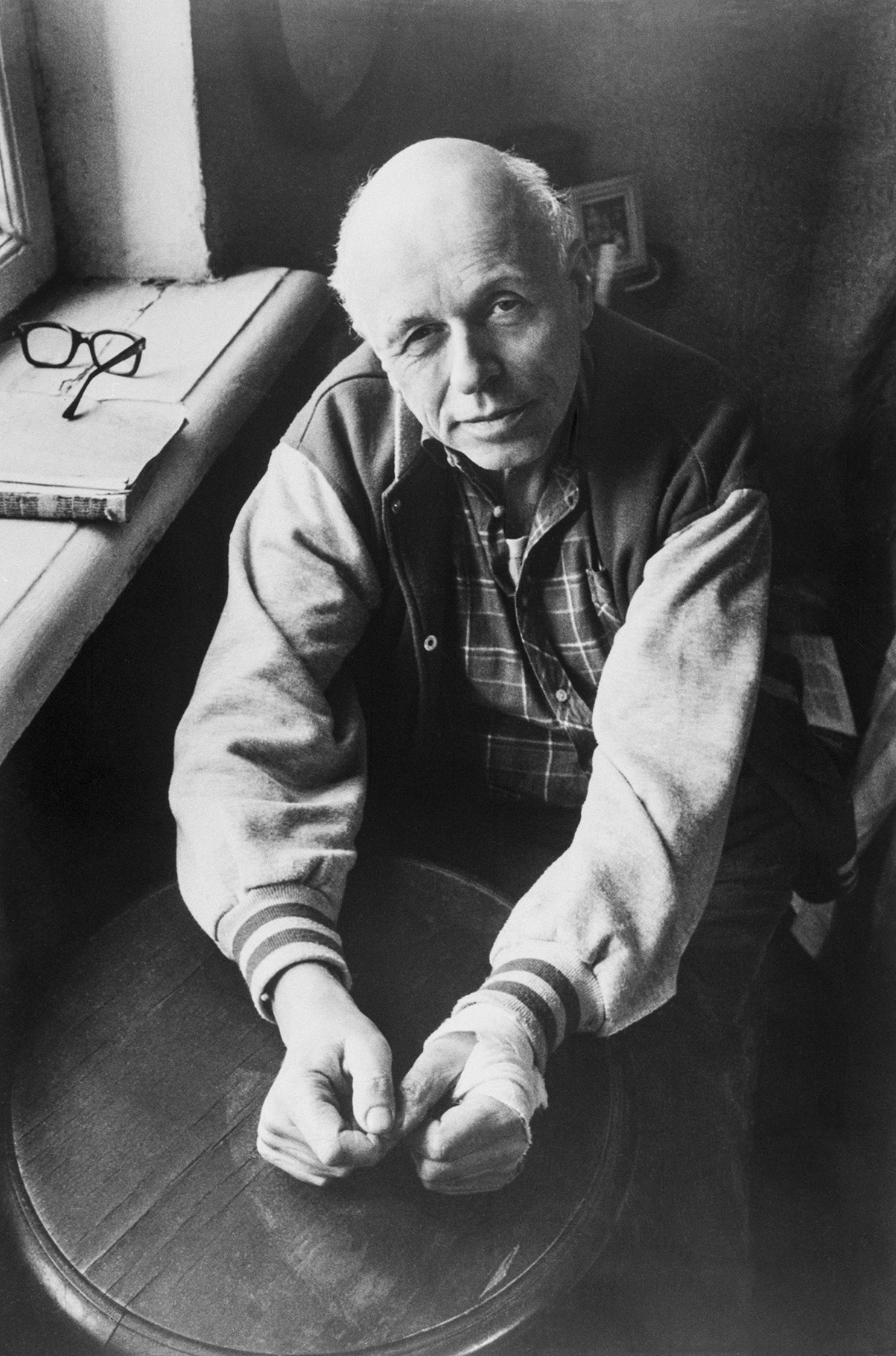

Andrei Sakharov

APHe goes on to tell how he shared his idea with Rear Admiral Petr Fomin, who headed the Soviet fleet’s nuclear weapons and nuclear tests. Fomin was shocked by the project, calling it a “cannibalistic” massacre of the civilian population. “I was ashamed and never talked about my project with anyone again,” Sakharov recalled.

But other methods were actively discussed. It was hypothesized that a torpedo armed with a superpowerful charge could be fired at a safe distance by fitting it with a timing mechanism. That way, it would explode at the right time, causing a tsunami. Another option was to turn the torpedo into a time bomb, and leave it off the US coast, able to be detonated at any time.

Could it really have worked?

Yes and no. A superpowerful bomb would indeed have produced a massive wave, but not, as the tests showed, on the scale imagined. This conclusion was reached independently by both the U.S. and the USSR.

Physicist Boris Altschuler says that in 2002 the Physics Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences was paid a visit by several US nuclear physicists: “One of them told me in private that as a young man at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, he had been instructed to calculate the parameters of a hydrogen bomb capable of creating a wave with the power to destroy the USSR.” He diligently did the sums as requested, and found that creating a 1 km-high tsunami in the Arctic Ocean would be feasible. Yet his report ended with a negative conclusion – the geographical size of the Soviet Union rendered the project impracticable. “The wave would not reach Moscow or the nuclear mines in Siberia. Not to mention the fact that the wave would move in concentric circles in all directions, including toward the US, Canada, and Europe,” said the report.

Sakharov’s colleague on the superbomb project, Yuri Smirnov, also poured cold water on the idea. The Atlantic is too shallow, while a giant tsunami in the Pacific would have destroyed only California. The Rockies would have stopped the wave going any further, which would have been pointless from a military point of view.

The US shelved the project, and Khrushchev, heeding the advice of the military and scientists, canceled the order to equip submarines with hydrogen bombs.

Will the real Sakharov please stand up

By the time Sakharov penned his memoirs, he had grown disillusioned with the Soviet government, admitting: “I tried to create an illusory world for myself as justification.” But back in the 1950s, he had been a committed communist and believed that the country that had incinerated Hiroshima and Nagasaki could one day do the same to his native land.

Moreover, he considered it his moral duty to neutralize this threat, and thus never expressed remorse for suggesting “cannibalistic” projects (for which he was awarded the title of academician (of the Soviet Academy of Sciences) at the tender age of 32). Sakharov genuinely believed that his ideas would prevent, not provoke, WW3. “Thermonuclear weapons have yet to be used against people in war. My most cherished dream (more profound than anything else) is for this never to happen, for thermonuclear weapons to curb war, but never be applied.”

“He lived too long in some extremely isolated world where little was known about events in the country, about the lives of people in other sectors of society, and about the history of the country in which and for which they worked,” noted writer and historian Roy Medvedev, who was Sakharov’s contemporary and later biographer.

By 1975, when Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, he was already the voice of the dissident and human rights movement in the Soviet Union, and one of the chief exposers of the Stalin-era crimes for Western audiences.

Read more: Andrei Sakharov: ‘Nuclear war might come from an ordinary one’.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox