Ivan the Terrible, the first Russian Tsar, once appointed Simeon Bekbulatovich, a Tatar prince, as the Grand Prince of All Russia. Simeon (born Sain Bulat) was converted to Christianity before that, no doubt. But still, a Tatar Khan on the Moscow throne, really? After all the damage the Horde did to Russia? Nevertheless, this freshly made sovereign indeed sat on Ivan’s throne for a year, issued ukases (orders), until Ivan regained the throne. What was this all about?

Simeon Bekbulatovich, the Grand Prince of All Rus'

Public domainThere is no clear evidence where Sain Bulat was born. But he had powerful aides who helped him get to Moscow. A descendant of Genghis Khan’s eldest son, Jochi, Sain was the nephew of Princess Kochenei, who was chosen as Ivan the Terrible’s second wife and baptized under the name Maria. Sain came to Moscow with her entourage in 1561.

As of 1570, Sain Bulat had become Khan of Kasimov, the town center of the Kasimov Khanate, which had also been conquered by Ivan the Terrible earlier. Since that time, Sain Bulat had been leading the Big (Main) Regiment of the Muscovy Tsardom Army – thus, he was considered the second most powerful man in the state after the Tsar. How could a Tatar prince reach such prominence? And what followed next was almost unbelievable.

Ivan IV "The Terrible" Vasilyevich

Viktor Vasnetsov/Tretyakov GalleryIn 1573, Sain Bulat was baptized under the name Simeon Bekbulatovich, and in September 1575, Ivan the Terrible placed him on the throne as the Grand Prince of All Rus’, while Ivan the Terrible retained the post of “Prince of Moscow”. Ivan continued to live in Moscow, in one of his estates on Arbat street. But, as historian D. Volodikhin points out, “coins with Simeon’s name were not minted, foreign diplomats did not have discussions with him, his name did not enter the military register and the treasury and insignia remained under the control of Ivan IV.”

As Ivan said to Daniel Sylvester, an interpreter for the British Russia Company, he had given Simeon the throne because of the “perverse and evil dealing” that Ivan’s subjects, the Russian princes, were commencing. But Ivan had retained control of the treasury and could return, as he claimed, at any time – Simeon had neither been crowned nor elected. But he was imposing enough for the boyars to respect him as a royalty – naturally, the Chinggisid dynasty was considered to be nobler than the Rurikids.

Sergey Ivanov. "The Darughachi (The Baskaks)", 1909. Baskaks were civil officers of the Golden Horde who collected taxes from Russians.

Sergey IvanovSoon after Simeon had become the Grand Prince, Ivan, who now called himself simply ‘Prince Ivan Vasil’yevich of Moscow’, filed a plea with Simeon. Humbly calling himself and his sons Ivan and Fyodor with diminutive names, and addressing Simeon as “Lord”, Ivan asked him to divide “members of the court, the boyars, the courtiers, the provincial nobility, and the attendants… We crave permission to rid ourselves of those who are not wanted by us.”

Ten years before, in 1565, Ivan had created oprichnina – he separated the land of Russia, making the most strategically important lands his property. With this move, he had deprived the old boyar aristocracy of their lands. Now, Ivan was simply making another move in this ‘game’. By declaring Simeon the Grand Prince, Ivan effectively withdrew all privileges he had given to towns, monasteries, and persons – all these were declared void and had to be renewed under Simeon. Simeon, in reality, couldn’t do anything without Ivan’s permission, and Ivan’s hands were now no longer tied – by not being the sovereign, he could see his orders carried out without the consent of the Boyar Duma.

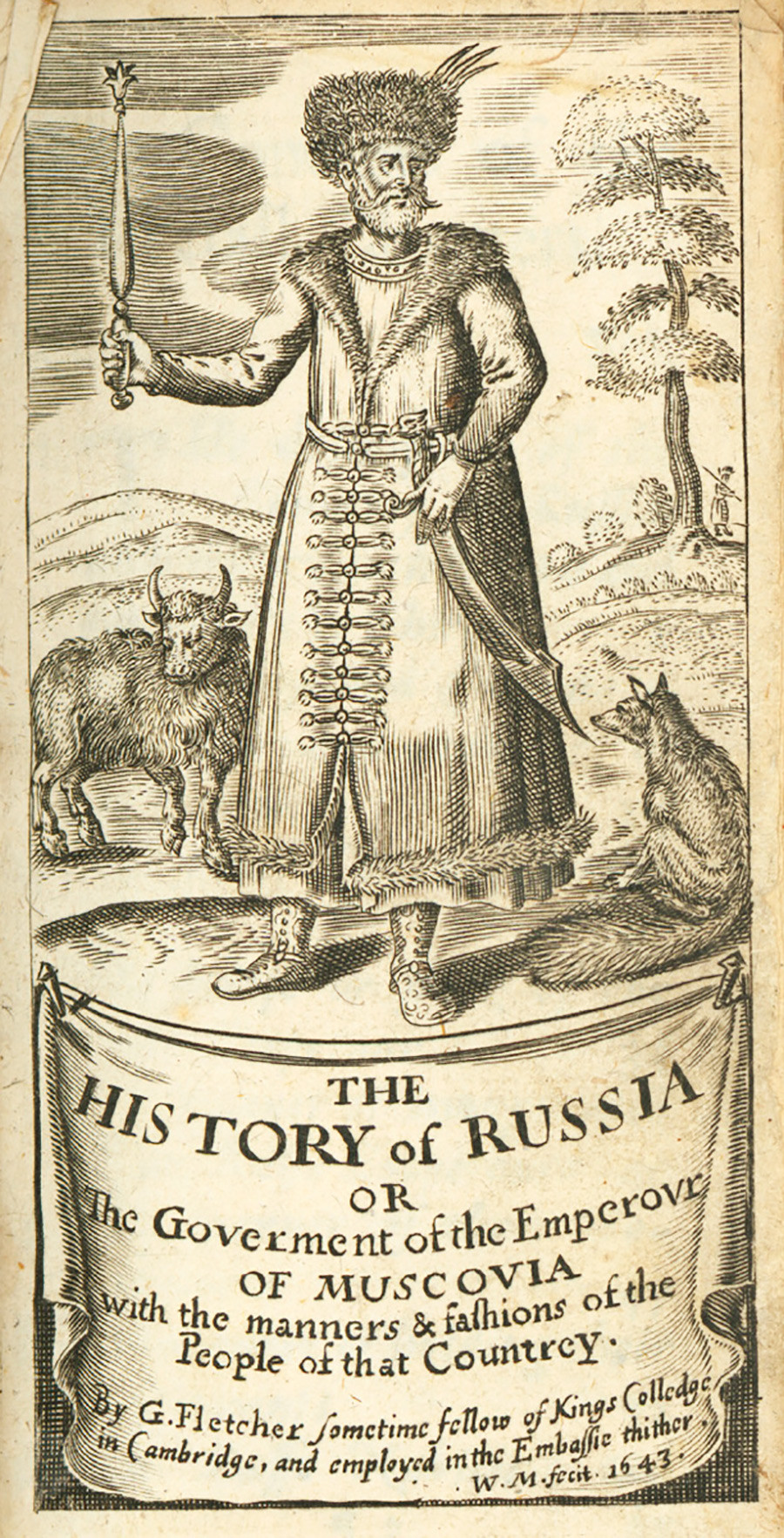

Giles Fletcher 'The history of Russia' titlepage, 2nd Ed. (1643).

Public domainGiles Fletcher, an English ambassador to the court of Tsar Fyodor, Ivan’s son, wrote at the end of the 16th century: “Ivan caused this new king to call in all charters granted to bishoprics and monasteries, which were all canceled. By this practice, he wrung from the bishoprics and monasteries (besides the lands which he annexed to the crown) a huge mass of money...” However, no clear records of Simeon taking away lands from the church were found.

There were more fantastic explanations. Some claimed Ivan had received a prediction that the Muscovy Tsar would die that year (1575-1576; in Russia in those times, New Year began on September 1). Other contemporaries claimed Ivan was “testing” his subjects for loyalty to him.

There are dozens of interpretations of this historical fact and there is still no consensus yet. Summarizing their thoughts, contemporary historian Donald Ostrowski says in his 2012 paper that this action was most likely caused by Ivan’s desire to temporarily abandon his responsibilities before the Boyar Duma and to act more freely – just as Daniel Sylvester claimed Ivan had told him.

Russian horsed archers of the 16th century

Public domainSurprisingly, Simeon’s short rule didn’t end at the gallows, for he was a descendant of Genghis Khan Khan and former Tsar of Kasimov. When Ivan took back his title, cities as big as Tver’ and Torzhok were granted to Simeon as an appanage, and Simeon became the Grand Prince of Tver’. Tver was a stronghold on the Western borders of the Muscovy Tsardom, and Ivan needed a military leader as experienced as Simeon, because the Livonian war was soon to begin. In 1577, 1580 and 1581, Simeon was seen again as the leader of the Main Regiment.

After Ivan died in 1584, Simeon was quickly stripped of his titles and privileges. There are rumors that he was blinded to prevent his possible ascension to the throne, but it’s most likely a legend. What is true is that False Dmitry the First, a short-lived self-appointed Moscow tsar, sent Simeon to the Kirillo-Belozersk Monastery, and later, next tsar Vasiliy Shuisky transferred him even farther to the Solovki Monastery on the White Sea.

Simonov monastery in Moscow.

M. Filimonov/SputnikSimeon returned to Moscow, the city he had once ruled, only in 1613, to witness Mikhail Romanov, the first tsar of the new dynasty, ascend to the Russian throne. Simeon died in 1616 in Moscow and was buried in the Simonov Monastery next to his wife. His grave and tombstone are now lost.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox